Balancing Act. Plus: Green Graves; Blockbuster; It's All Academic; The Facts of Life; Lessons in Lunacy

Andrea Avruskin '89 keeps the cast of a Vegas extravaganza on their toes (and on the trapeze)

They emerge from the pool like visions from dreams and nightmares—primordial lizards, winged angels, horned devils. A burst of fire rolls across the water. A tree rises from beneath the surface, figures clinging to its broken branches. They swing. They fall. They climb back up. The celestial heavens come alive on the ceiling of the domed theater, and for another seventy-five minutes several dozen performers display the kind of athleticism and artistry that audiences have come to expect in a Las Vegas extravaganza.

Meanwhile, in a medical clinic twenty feet off-stage, Andrea Avruskin '89 is typing madly. As an athletic trainer and on-call EMT for Le Rêve, Avruskin has already been at work for nearly six hours. She has spent three hours dealing with cast members who are out of commission due to severe injuries (shoulder surgeries, lumbar disc problems, concussions), then another three treating those who are performing despite ankle sprains and muscle pulls. Finally, once the show starts, she is able to update their medical charts. But she keeps her radio nearby, listening for the inevitable injuries—everything from ear problems and rope burns to decompression trauma and pelvic fractures. "People run in bleeding, scratched, or bruised," says Avruskin, a native of Rockville Centre, New York, who has lived in Las Vegas for a decade. "Usually, we treat them and send them back out. We have to use bandages that won't show up on stage and will stay on in the water. So we've gotten pretty creative."

Housed at the Wynn Las Vegas resort, Le Rêve is the latest creation of Franco Dragone, the former creative director of Cirque du Soleil. Its title is French for "The Dream," and the production offers a surreal experience for the 1,606 people squeezed into the theater-in-the-round, whose centerpiece is a pool filled with a million gallons of water. The performers— French synchronized swimmers, Polish hand-balancers, Canadian acrobats—transfix the audience with an illusion of danger that frequently turns out to be real. Thus, for the nine employees of the health services department, the job is part medical drama and part quirky ensemble piece. "It's a mix of 'ER,' 'Northern Exposure,' and 'M*A*S*H,' " says Avruskin, who temporarily took over as head of her department in October and was honored as one of Wynn's employees of the month. "There are so many different personalities, nationalities, and beliefs about medicine and how to treat an injury. People will come in and talk about everything from 'Star Trek' to politics, so the conversations can be so varied and so very weird."

Avruskin is clad all in black, right down to her socks, so as not to distract from the spectacle if she has to rush to help an injured performer. Not that she isn't comfortable on stage. A longtime dancer, Avruskin produced, directed, and choreographed her own dance concerts on campus. For a while she was a pre-med major, only to be told that her C in physics would make it difficult to get into medical school. So she applied for an independent major, hoping to combine two passions—dance and biology. "They rejected me. They said, 'There's no way you'll use those two things together in the real world,' " she recalls, obviously enjoying the irony, as she is surrounded by tango dancers and training tape. "Then I happened to break my ankle in the snow on the way to dance class. I was sent to physical therapy, and I realized I could do orthopedics without being a doctor."

For three years—while she worked at O (Cirque du Soleil's water-themed extravaganza at the Bellagio) and earned a doctorate in physical therapy from Creighton University via distance learning—Avruskin danced as a showgirl in a Vegas revue called Jubilee! She still dances in small productions, along with serving as a volunteer reader for the local National Public Radio station, an actor in independent films and TV commercials, and a part-time model.

One of her primary challenges with Le Rêve is that many of its cast members are former Olympians or other champion athletes who are accustomed to training hard, peaking for a competition, then taking a break to heal. But as entertainers, they're in it for the long haul. "We have maybe twenty days off a year, so we have to teach them how to train sub-maximally, but enough to keep them in shape and injury-free," says Avruskin, who served as a physical therapist at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. "We have no leeway regarding time off and time to recover if we want to keep them in the show. And the performers expect us to get them back to doing triple flips and trapeze in half the time that a normal person would take just to get off crutches."

Green Graves

A final resting place for the ecologically minded

Fred Gradel loved nature. The longtime Statler waiter was known for gardens that would make the Plantations green with envy; his home was filled with plants rescued from Hotel school dumpsters and rehabilitated to lush foliage and flower. So when he died suddenly in mid-October at age forty-six, it didn't surprise anyone that his burial would reflect his lifelong passion.

Under leaden skies, 150 mourners wearing sensible shoes trekked into a hollow adjacent to the 4,000-acre Arnot Forest to lay Gradel to rest. Four grapevines snaked beneath a simple wooden box suspended over a grave lined with Norway spruce boughs. After a eulogy, psalm, and prayer, eight men used the vines to lower the casket, bearing a message of farewell: "Beloved son, brother, uncle. Peace." As the mourners departed, each laid a bough atop the coffin, leaving behind the mound of earth that would later fill the grave.

Prior to the Civil War and the cross-country voyage of Abraham Lincoln's embalmed body, most Americans got a "natural burial" in one way or another. There was no funeral industry, embalming was rare, and—like weddings—interment was usually a simple affair. Today, the average burial costs more than $7,000. Beneath the manicured turf of a conventional cemetery, the typical ten-acre tract contains enough wood to build forty homes and enough embalming chemicals to fill a swimming pool. And that's not counting the pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizer required to maintain a golf-course quality lawn. "Enough metal is diverted into coffins and burial vaults in the U.S. each year to build the Golden Gate Bridge," says author Mark Harris, whose Grave Matters documents the modern funeral industry and the natural burial movement, "and enough concrete is diverted to build a two-lane highway from New York to Detroit."

Enter the green cemetery movement— a nascent strategy for conserving natural landscapes, reducing costs, and bringing the realities of death back to American burials. The first one in the U.S., the Ramsey Creek Preserve in South Carolina, opened in 1998 and now covers more than seventy acres, with 100 plots filled and another 350 pre-sold. The 100-acre Greensprings Natural Cemetery Preserve in Newfield, where Fred Gradel was laid to rest, has sold more than 100 plots; some twenty people have been buried there since it opened in 2006. "We environmentalists get in the habit of asking people to give up this or that," says Greensprings vice president Carl Leopold, founding president of the Cornell-affiliated Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research and owner of one of the first plots sold. "This isn't giving up anything. It's a matter of avoiding a kind of synthetic system that's built up over the decades, wanting to fix up the body so it's presentable."

At Greensprings, located sixteen miles from the Cornell campus, families pay just $500 per burial. They choose a shroud or a biodegradable coffin; no metal caskets or concrete vaults allowed. One man built elaborately hinged wooden coffins for himself and his wife. Another family spent the night before the burial washing their loved one's body and stitching satin ribbons to her shroud. Embalming is forbidden, and landscaping is restricted to native plants. Pre-sales allow people to choose from more than 1,500 plots; executive director and longtime volunteer Joel Rabinowitz '71, BA '73, says he's seen a brisk growth in interest in recent months. "I've become convinced," he says, "that there are far more people out there who are excited about and attracted to the idea of natural burial than cemeteries that provide it." Harris sees the movement extending far beyond the tree-hugging crowd. "In the end, it's about simplicity, a less expensive way of burial, a return to tradition," he says. "It's about family control, and it speaks to old-fashioned American values."

According to an AARP survey, a majority of America's 75 million Baby Boomers have no intention of having their bodies buried; they're opting for cremation. But for those concerned about global warming, it's tough to justify. "It's not environmentally sound," says Ithaca city forester and Greensprings Ecological Insight Committee member Andy Hillman. "You have to burn a body at 1,600 degrees Fahrenheit for four hours, so you create a carbon debt at the point in your life where you can't pay it back." Furthermore, if a body has metal dental fillings, cremation produces volatized mercury. Even so, Greensprings sets aside an area for cremains, in part to preserve the land from development. The first year of burials at Greensprings has spanned the generations, from a stillborn infant to elderly locals, even the long-ago cremated remains of a board member's parents. "We've had more than one instance where a child was to be buried," says Leopold, "and the father said, 'I'm going to dig the grave and fill it.' I think some people feel that if they're able to take the shovel and actually do the work, it's something personal that would please the departed one."

Blockbuster

A toy that's more than child's play

A nine-year-old used them to group plants and animals into species. A teenage musician wrote lyrics with them. A drama teacher used them to show a high school student the difference between her role and herself. Doctoral students have mapped out their dissertations with them.

A nine-year-old used them to group plants and animals into species. A teenage musician wrote lyrics with them. A drama teacher used them to show a high school student the difference between her role and herself. Doctoral students have mapped out their dissertations with them.

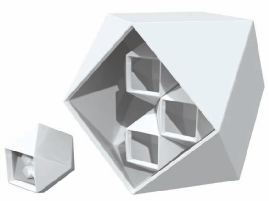

They're ThinkBlocks, white plastic polyhedrons that teach kids (and everyone else) how to develop their minds. Educational theorist and entrepreneur Derek Cabrera, PhD '06, designed the blocks to develop the four skills that he says underlie all thought: making distinctions, organizing systems, recognizing relationships, and understanding different points of view. Some blocks are magnetized and can stick together, to represent related ideas. Smaller blocks fit into larger ones, to show the concept of parts within a whole. Mirrored sides help teach the idea of perspective, and the blocks can also be labeled with magnetic tiles or a dry-erase marker. Says Cabrera: "They're like a three-dimensional whiteboard."

Cabrera became inspired while teaching an education course on systems thinking; the more abstract the concepts became, the more difficulty his graduate students had. Educators have known for decades that people are better able to understand an idea when they hold an object that represents it, he says. He designed the blocks (a patent is pending) and launched a company, ThinkWorks, with Laura Colosi '92, PhD '02. The blocks retail for $79.99 on their website, www.thinkandthrive.com. Now they're marketing them to parents and educators, with focus groups taking place in Ithaca schools. Their aim is nothing less than to change the way kids are educated, Cabrera says. "You can use Legos to build any thing you can think of. With these, you can build any idea."

It's All Academic

Neurobiologist Charles Walcott, PhD '59, has served as dean of the faculty since 2003. And yes: he's really an expert in the behavior of loons.

Cornell Alumni Magazine: What issues are the faculty most concerned about these days?

Charles Walcott: They are always concerned about salaries, maintaining them at a reasonable level compared to the competition. There is the question of granting honorary degrees, which has been posed by our colleagues in the Medical school and will require a significant amount of discussion. Another matter is renewal of the faculty as professors retire. And those of us who are getting toward that time are interested in how to maintain relations in a way that will serve the University's interests and our own.

CAM: How do faculty salaries compare with our peers?

CW: Through an aggressive series of raises over five or six years we are now at the middle of the pack. But you have to be careful that you don't slip behind, because other institutions may decide they don't want to be at the bottom.

CAM: Are there specific departments that will see the most turnover?

CW: It's going to be throughout the University—and we are not alone in this. Every university is trying to get the best faculty, so you'll have real competition for quality.

CAM: Does Cornell's main recruitment challenge boil down to geography?

CW: I think it does. One problem is that of trailing spouses. That's a non-proper term these days, but when you hire somebody there is often another person who needs gainful employment. That is a real issue if you are in a fairly isolated community, which Ithaca is. It's a particularly serious problem when you want to hire a woman. For instance, in biochemistry, if you are a man the chances are 25 percent you are married to a professional spouse who is going to require a job. If you are a woman, the number is 75 percent.

CAM: How challenging is it to recruit racially diverse faculty? For instance, the local school system has had some high-profile racial incidents. Are you concerned that could turn off a person of color who might be thinking of coming to Cornell?

CW: I think it makes it more difficult. Ithaca always has had a certain black population, which is unusual in Upstate New York, and you would think life would therefore be easier here, but I'm not convinced it is.

CAM: How has the turnover of the presidency affected relations with the faculty?

CW: President Lehman's resignation did cause a great deal of unhappiness; it was largely that there was no consultation and no warning, and they really liked what they saw of Jeff. But it has calmed down, and my sense is that they like President Skorton. I have found his administration collegial, pleasant, and easy to work with. But I think most faculty have no idea about the administration and couldn't care less, as long as they have a place to park and they get paid.

CAM: Speaking of parking, how big an issue is it?

CW: All you'd need to do is ban on-campus parking, and you could fill Bailey Hall with irate faculty. [He laughs.] I think you have to have some perspective. Cornell has a very nice parking arrangement. But in the old days, if you were a chemistry faculty member you had your own reserved space in Baker courtyard, whereas nowadays it is a bit of a competition.

CAM: Does being dean of the faculty rate your own space?

CW: No, I get to fight with everybody else.

CAM: You've been a vocal proponent of creating a faculty club beyond what's currently offered in the Statler at lunchtime. Do you see the lack of such a facility as a major detriment?

CW: It's a real problem in several ways. It's a problem for junior faculty because the club is a place where they can meet other faculty and that's important from a social point of view. Second, it's unfortunate because more and more research is interdisciplinary and a lot of that comes about almost by accident—you happen to sit with somebody at lunch and chat, and that kind of cross-fertilization is becoming harder and harder to do. But a university club is a bit like the Tragedy of the Commons. It's nobody's first priority.

CAM: How much of a concern is academic integrity—in an age where students can copy papers off the Internet or cheat on exams via text message? CW: There is a whole series of reasons why we need to be more concerned about integrity; a committee of students, faculty, and staff will spend the spring looking at the issue. Something like 60 percent of high school students admit to some level of academic dishonesty. There is a feeling in society as a whole that if you can get away with it, it's OK—and that is intolerable in an institution of higher education. Another element is that we have many foreign students who come from places where academic matters are handled differently. In some cultures, it's a sign of respect to quote extensively, and you don't need to attribute it.

CAM: Finally, how does studying animal behavior help you lead the Cornell faculty? You are, after all, an expert in the behavior of loons.

CW: I've always been very specific that the loons I study have feathers. [He laughs.] I think it helps to have a sense of humor, a kind of sympathy with the human condition—listening to folks and trying to be helpful. That's what this job is all about.

The Facts of Life

Sari Locker '90 aims to be the Gen-X Dr. Ruth

Sari Locker '90 sits in a corner booth at Popover Café on Manhattan's Upper West Side and smiles when her lunch date apologizes for being a couple of minutes late. No worries, she says. She was just chatting with the waiter, who happened to be revealing some intimate matters of sexual frustration and family dysfunction. "I'm not sure why," she shrugs. "I don't even think he knows who I am."

Apparently, when you're a nationally recognized sex educator, you're never quite off duty. Much like the mother of media psychology, Dr. Joyce Brothers '47, Locker has made herself a ubiquitous presence. She can be seen discussing intimacy issues with Ann Curry on "Today," examining the Britney-Paris-Lindsay bad girls phenomenon with Bill O'Reilly, and bantering playfully with Conan O'Brien. In the mid-1990s, she hosted 200 episodes of her own sex talk show, "Late Date with Sari," on Lifetime. Such wide exposure has been Locker's goal from the beginning. "In the field of sexology, there are sex educators, sex counselors, and sex therapists," she says, biting into an egg-white omelet. "And I always felt that, rather than working one-on-one with someone in counseling or therapy, I was best suited to be an educator—teaching a class or a large group of people. I always had this idea that to help the most people I would go to the media to have the biggest audience."

But Locker's career is based on more than repackaging locker-room talk for mass consumption. Yes, she is the monthly sex advice columnist for Maxim magazine, a publication for men who like to view scantily clad women. And yes, her four books have titillating titles like Mindblowing Sex in the Real World and The Complete Idiot's Guide to Amazing Sex. But with a degree in educational psychology from Cornell, a master's in human sexuality education from Penn, and a PhD in developmental psychology from Columbia, Locker comes at her topic from an academic angle. Only rarely does she resort to sexual slang, for instance. "In general," she says, "I tend to use clinical words."

Her range of forums is remarkably broad. One day she might be on VH-1, commenting about "Awesomely Bad Dirty Songs," the next she might be lecturing a group at Missouri's Central Methodist College. For nearly two decades she has traveled the country, speaking on subjects ranging from talking to teens about dating to common myths about sexuality. Last April, Cornell students packed Statler Auditorium to hear her speak at an event sponsored by the student-run Sexual Health Awareness Group (whose acronym is, in fact, "SHAG"). "She gave a very refreshing talk about sexuality in the context of us as college students in this day and age, how we develop our own sexuality, and how it's influenced by other people and the media," says SHAG president Liz Franzek '08. "It was standing room only, which was very exciting because we didn't know how it would be received on campus."

Her range of forums is remarkably broad. One day she might be on VH-1, commenting about "Awesomely Bad Dirty Songs," the next she might be lecturing a group at Missouri's Central Methodist College. For nearly two decades she has traveled the country, speaking on subjects ranging from talking to teens about dating to common myths about sexuality. Last April, Cornell students packed Statler Auditorium to hear her speak at an event sponsored by the student-run Sexual Health Awareness Group (whose acronym is, in fact, "SHAG"). "She gave a very refreshing talk about sexuality in the context of us as college students in this day and age, how we develop our own sexuality, and how it's influenced by other people and the media," says SHAG president Liz Franzek '08. "It was standing room only, which was very exciting because we didn't know how it would be received on campus."

Locker teaches a once-a-week adolescent psychology class to graduate students at Columbia, which harks back to her moment of career epiphany during her sophomore year on the Hill. She was seventeen, having skipped a couple of grades in school, and she was taking adolescent psych. "I wanted to write a final paper on a topic that really mattered to me," she says. "That's when it dawned on me that I always talked to people about sex. Friends always asked my advice, especially about losing their virginity. I was not sexually active in high school, but I knew a lot about it."

Her knowledge came from a variety of sources. Raised in Fort Lauderdale and on Long Island, Locker grew up in a household where her mother always talked openly about sex and where her love of animals—puppies, hamsters, turtles—gave her an early understanding of the clinical aspects of breeding. Always precocious, Locker recalls the first time she heard Dr. Ruth Westheimer on the radio: "I was eleven. I would listen to the sex question, turn down the radio, quickly answer it, and then turn the volume back up to see if I had the same answer she did."

At age eleven?

Locker grins. "She'd always just say, 'Try lubrication.' "

After writing that fateful paper at Cornell, Locker immersed herself in scientific journals on sexology and began traveling the country as a near-peer educator, teaching high school students about making better sexual choices. She also stood in front of Willard Straight Hall, microphone in hand, lecturing her fellow Cornellians. "It was remarkable," recalls her longtime friend Daniel Kaufman '89. "Even back then she was fearless and ambitious and totally dedicated to educating people about sexual choices."

After graduation, Locker began studying TV in earnest, watching the daytime talk shows, tracking when the guest expert would come on and how many sound bites he or she used. She contacted producers, pitched herself as a young expert, and, at the age of twenty-two in 1992, snagged her first television appearance. Geraldo Rivera held up a couple of props and introduced his guest by saying, "When we come back, this woman will put this condom on this banana." So began a career whose focus has evolved along with the sexual culture. "My generation was the first to come of age during the time of AIDS, so we had more fear of sex than knowledge of the pleasure of it," she says. "Today, twenty-somethings are in a different situation. They're bombarded with sexual images from TV and the Internet. The quantity is unbelievable. But my goals are still the same—to help people understand and feel good about their sexuality."

Lessons in Lunacy

Since 1978, the Cornell Lunatic has been offering humorous cartoons, articles, and essays—including this detail from a 1999 panel, entitled "Finding Yourself At College." On April Fool's Day, Lunatic Press will publish an anniversary anthology, Lunacy: The Best of the Cornell Lunatic, edited by magazine founder Joey Green '80. www.lunaticpress.com