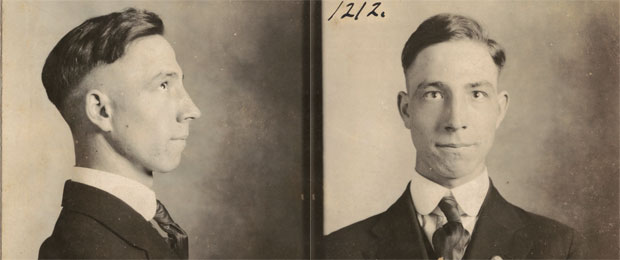

Wanted: Franklin Koch’s 1918 mug shots following his arrest for homosexual acts.

The two small, black-and-white photographs show a sweet-faced man who looks to be in his late teens or early twenties; he’s young enough, in any event, to sport a smattering of acne across his cheek and chin. He’s neatly dressed—three-piece suit, stiff-collared shirt, pocket handkerchief, lapel pin—and his hair is coiffed in the style of the day, shorn high at the sides and floppy on top. In the left-hand image he’s in profile, eyes turned heavenward; in the right one, he stares directly into the camera with a classic deer-in-headlights expression. The longer you look at the tiny photos, the more startled and frightened he seems.

Of course, it’s impossible to know for sure what this young man was feeling—but the context makes it easy to surmise. The images are mug shots from December 1918, when one Franklin Koch was arrested in Scranton, Pennsylvania. The charges: “sodomy and buggery.”

Viewing his mug shots in Kroch Library makes you wonder what became of poor Mr. Koch—whether he served time, lost his job, got beaten up, was rejected by his family. Inevitably, it also prompts thoughts of how different his life would have been if he’d been born a century later. While homosexual acts were crimes in Pennsylvania in Koch’s day, this spring the state became the nineteenth in the U.S. to legalize gay marriage. The man who was slapped into cuffs for consensual sex could have shopped for an officiant on EngagedGayWeddings.com.

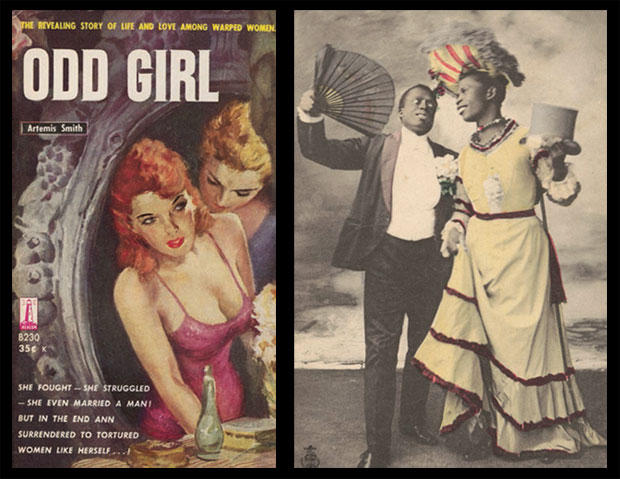

Gender bending: A Fifties-era pulp novel (left) and a hand-colored postcard (right) of a French cross-dressing couple, circa 1900.

According to the University Library’s Brenda Marston, such musings are exactly what the creators of “Speaking of Sex” were aiming for. The exhibit, which opened in February and runs through mid-October, celebrates the twenty-fifth anniversary of Cornell’s Human Sexuality Collection, a milestone the University marked with events throughout the 2013–14 academic year. “We were unique in having an archival focus and in documenting the social movements related to sexuality,” says Marston, who has served as the collection’s curator since shortly after its inception. “We were pioneering both in giving prominent attention to lesbian and gay history and also in documenting sexuality broadly—saying it’s important to look at all the different margins of sexuality and the kinds of sex that have been considered deviant. We were interested in transgender rights before a lot of other people, because our focus is looking at what is excluded and how new communities are forming and defining themselves.”

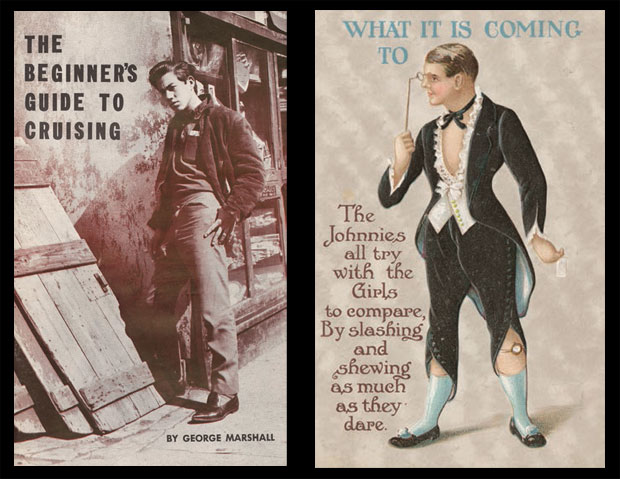

Out on the town: George Marshall’s 1964 guide (left) noted that “the cruiser’s ideal is a gay who can be had (though not too easily) and once had is, one way or another, fun.” Right: A turn-of-the-century British postcard.

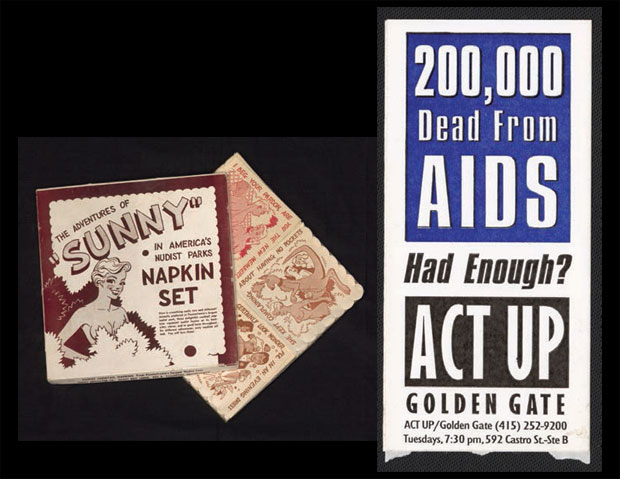

“Speaking of Sex,” on display in Kroch’s main gallery, offers a glimpse into the depth and breadth of the Human Sexuality Collection—an archive that boasts some 10,000 volumes and other materials comprising more than 1,430 cubic feet of storage space. There’s a 1926 advice book quaintly titled The Question of Petting. A 1955 “Dating Ladder” that prescribes five rungs of social interaction, topped—naturally—by engagement and marriage. A 1997 copy of Roberts’ Rules of Lesbian Break-Ups. The Fifties-era pulp novel Odd Girl, touted as “the revealing story of life and love among warped women.” Turn-of-the-last-century photos and postcards of same-sex couples and cross-dressing performers. An 1813 edition of Henry Fielding’s The Surprising Adventures of a Female Husband. A program from the musical La Cage Aux Folles. The Beginner’s Guide to Cruising. A poster from the 1973 X-rated romp Campus Girls, “in color for ladies and gentlemen over 21.” A sticker promoting the San Francisco chapter of ACT UP (“200,000 dead from AIDS—Had Enough?”). A box of nudist-themed napkins. Buttons supporting abortion rights and opposing sodomy laws. Cards advertising sex workers, from a “shemale transvestite” to a gal named Maria who boasts “the best nipples in London.” One spare, handwritten slip of paper bears a phone number and a promise: “Kinky But Kind.”

Stored in Kroch and in the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections’ climate-controlled annex at Cornell Orchards, the Human Sexuality Collection has its roots in the early Eighties. Its chief architect was David Goodstein ’54, longtime publisher of the gay magazine the Advocate. “He approached the University because he felt there needed to be scholarly research into sexuality as a subject—that it should be part of the academic mission,” says University Archivist Elaine Engst, MA ’72. “Rather than buying a lot of books on sexuality, the decision was made to explore the idea of a collecting effort.” An early ally was Goodstein’s friend Bruce Voeller, former executive director of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Voeller was president of the Mariposa Education and Research Foundation, which promoted understanding of LGBT issues; he and Goodstein sought a home for its papers and the many other documents chronicling the gay rights movement they and their colleagues had compiled over the years. From the start, founding staff recall, Goodstein was adamant that the collection have a broad mandate. “He wanted the concept to be all of human sexuality,” says Tom Hickerson, who chaired the Department of Manuscripts and University Archives at the time and is now at the University of Calgary. “While he focused on collecting materials on gay and lesbian life, he wanted that portion of society and the issues around it to be seen in the context of all humans. He didn’t want it to be pulled out as distinctly different, but to be on a continuum of sexual experience.”

While Goodstein’s sudden death in 1985 caused some delays—and, Hickerson recalls, meant that the University received substantially less support than he’d originally pledged—trustees ultimately approved the collection’s establishment, and the first items were accepted in 1988. “It was a bold step,” says Marston. “At the time, there weren’t other major research libraries paying close attention to sexual politics.” Yes, sex was the focus of Indiana University’s Kinsey Institute—but, Hickerson notes, it approached the subject as did its namesake researcher. “He looked at it from the biological,” he says. “We consciously did it from a social perspective.”

How controversial was the archive’s creation? Memories and opinions differ. As Marston recalls it, “There wasn’t really any official pressure on the library or concern from alumni that was expressed.” Engst remembers the reception as similarly low-key. “My understanding is that it was seen as something we should do, and that the University got very few negative reactions; you could count them on one hand, maybe two,” she says. “My recollection is that the concern wasn’t that people would be outraged, but that they would giggle, because sex makes them uncomfortable.”

Tragedy and comedy: A sticker advertising ACT UP meetings in San Francisco (right), and a set of paper napkins from the Fifties bearing bawdy cartoons set in nudist parks (left).

But Joan Jacobs Brumberg, professor emerita of human development, recalls vocal opposition from some at the library and on the faculty, at least during the formative stages. “When the archive was proposed, it was not universally welcomed,” she says. “There were people who thought it was silly, that sex was not an appropriate subject for scholarship. I was a historian of women, so I was already tuned into the idea that the history of sexuality could illuminate issues about women and their place in society—but there were plenty of faculty members and librarians who weren’t used to that. So let me emphasize: we are celebrating something today that was not universally welcomed when it began.”

To avoid sensationalizing the subject matter, Engst recalls with a chuckle, the press releases and in-house articles announcing the archive were almost comically circumspect. “When we did the early publicity, we were very, very cautious,” she says. “The joke was that we were making sex boring. We were talking about it in a dry, scholarly fashion, deliberately trying to dial it down.” Nevertheless, an Associated Press story on the collection’s debut ran in dozens of papers around the country. “With one fell swoop, it established our presence nationwide,” says Hickerson. “And, my goodness—what a diverse array of headlines that story appeared under. They reflected many different political views.”

The publicity, Hickerson says, prompted numerous inquiries from people seeking to donate materials; it also engendered hate mail, much of it informing Hickerson that he’d be spending eternity in warmer climes. “The University received a fair amount of critical communications, some from alumni and some from others,” Hickerson says. “Some were hateful against gays and lesbians; people were upset that the University was giving its imprimatur that this was a legitimate part of society.” For years, Hickerson kept a favorite postcard, sent by someone with no clear affiliation to Cornell but plenty of righteous indignation. “It was crowded with writing, all around the edges,” he recalls drolly. “The person was trying to get in all the slurs they could.”

In the intervening quarter century, of course, American society has made remarkable advances in LGBT civil rights; the collection’s early days fall at roughly the midpoint between the present and the Stonewall riots of 1969. Shannon Minter, JD ’93, recalls using the archive shortly after its establishment, not only for research (first as a grad student in English, then as a law student), but as a source of personal inspiration. Born biologically female in a socially conservative Texas family, Minter identified as a lesbian during most of law school, but eventually transitioned to male. He’s now legal director of the San Francisco-based National Center for Lesbian Rights, whose papers will eventually come to the archive. “Cornell was the first time in my life that I didn’t feel lonely,” says Minter, who faced rejection by his family and harassment in school. “I had a sense of home and community. It was life-changing.” The collection’s very existence at Cornell, he says, played no small part in that. “Until recently, one of the most dangerous aspects of being a gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender young person was a lack of role models, or of any recognition of LGBT people in history or contemporary society,” Minter says. “We now know that kind of silencing and stigma has lifelong negative consequences. So it’s hugely significant to have a university so openly recognize and embrace LGBT people and their history, particularly around sexuality. I can’t stress enough how important that normalizing message is—that this is part of human history, we recognize you exist, you’re a valued part of our academic community, we’re not embarrassed or ashamed to acknowledge you. To have the archives be part of a library of international scholarly importance, where people from all over the world come to study, sends a great message to young people. You can’t really have a sense of the future—that there is someplace for you in the world—unless you fundamentally think that who you are is OK.”

No laughing matter: in a 1965 comic published by the New York City health department, a teenage boy learns some tough lessons about venereal disease after contracting syphilis.

A generation earlier, Human Sexuality Collection donor Jearld Moldenhauer ’68 had no such resource on campus—so he created one. The year before Stonewall, Moldenhauer founded Cornell’s first gay rights group, the Student Homophile League. It was only the second such chapter on an American campus, after Columbia’s. “A lot of my straight friends joined, but many of the gay ones were afraid of what it might mean for their future, in terms of employment,” he recalls. “I was afraid too. I used a pseudonym for a week, until I forgot what it was.” Moldenhauer went on to found another chapter at the University of Toronto, publish the gay monthly the Body Politic, and open Toronto’s Glad Day Bookshop, which remains in business. A few years ago, he gave the archive some 175 books on German LGBT history—volumes he’d painstakingly collected over the course of decades because the same works had been burned under Hitler. Asked what having something like the Human Sexuality Collection on campus might have meant to him in his younger days—when he was so in denial about his sexual orientation that he was engaged to a woman—Moldenhauer ponders the question for a moment. “On a personal level, I think I would have believed in myself more and had a few more years of an enjoyable life,” he says finally. “I would have had deeper and more intimate relationships, because all of that depends on a social support system.”

For Hickerson, one of the most powerful memories of working with the collection is a trip to rural North Carolina he and Marston took in 1989. They were retrieving the personal papers of Robert Lynch, a gay man of mixed race whose varied résumé included practicing securities law, writing poetry, collecting outsider art, and serving as a consultant to the Dance Theatre of Harlem. The trove of materials included extensive correspondence, diaries, family photos, erotica—and, Hickerson remembers most vividly, florid biohazard posters from Lynch’s hospital stays for AIDS treatment. He and Marston rented a car from the airport and drove into the hill country; Lynch, by then gravely ill, had to be supported on the short walk to a storage building. Hickerson’s voice catches at the memory. “A couple of days later his sister called us and told us he had died,” he says. “She thanked us, and told us that he had stayed alive until he could give us his papers.”

Images provided by Kroch Library / Cornell University / Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections