Lowry sporting one of his signature suits on “Antiques Roadshow.”ANTIQUES ROADSHOW for WGBH, (c) WGBH 2018

Thanks to his many TV appearances, fans often stop Nicho Lowry ’90 on the street—but, he admits, “it’s more likely that the person recognizes my suits than myself.” A longtime expert on PBS’s popular “Antiques Roadshow,” Lowry is known for his distinctive wardrobe: vividly colored three-piece suits that he has custom tailored in the UK. “The original appeal was to look more like an appraiser on television, but then I realized I had a fetish for plaids and tartans, so I kept pumping up the wattage,” says Lowry, who owns more than two dozen of the bespoke ensembles. “As far as recognition goes, it has worked very well for me.”

Chatting with CAM last spring at his family’s Manhattan auction house, Lowry is—as he puts it—“dressed fairly demurely today.” His trousers and vest are tweed windowpane plaid (he’d doffed the jacket earlier) in bright shades of green and red. His shirt, white with pink and blue stripes, is accessorized with shocking pink cufflinks, and his tie is a purplish burgundy, enlivened by a repeating print of small starbursts. His ample moustache is waxed into upturned curls; a hoop glints from one earlobe; his hair, silver at the temples, is neatly slicked back and pinned with little pink barrettes.

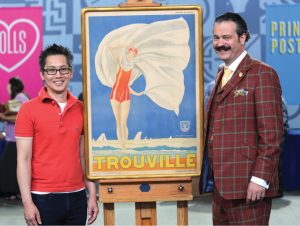

Appraising a vintage French travel poster on the program.ANTIQUES ROADSHOW for WGBH, (c) WGBH 2018

Lowry’s signature look—along with his passion for vintage posters, his area of expertise—has made him a familiar character on “Roadshow,” the PBS stalwart that brings droves of hopeful treasure-toters to appraisal events at cities around the country. (A 2017 show promo, dubbed “Nicho’s Checkered Past,” offered a tongue-in-cheek roundup of his sartorial highlights, including a moment when he told a guest that seeing her rare 1930s ads for a bygone brand of refrigerators “sets my tartan all a-twitter.”) Lowry is president and principal auctioneer at Swann Auction Galleries, a third-generation family business that specializes in works on paper including books, maps, manuscripts, autographs, prints, and drawings. As the New York Times observed in a 2016 story on the art of auctioneering, noting a pedigree that traces to Swann’s founding in 1941: “Mr. Lowry practically emerged from the womb with a hammer in hand.”

Such bona fides helped Lowry land the gig as the “Roadshow” poster expert more than two decades ago. In the intervening years, he has educated audiences about a wide variety of items—from an Art Nouveau ad for French cigarette papers to Rosie the Riveter images distributed as World War II morale boosters. He has weighed in on posters promoting European travel, the Ringling Brothers circus, an 1885 reunion of Civil War veterans, a long-defunct San Francisco water park, performances in Paris by Wild West star Buffalo Bill, the 1962 World’s Fair in Seattle, a lost silent film from 1914, and much more. “First and foremost, posters are unintentional art,” Lowry says, explaining what drives his love of the medium. “These were not things that were meant to be saved; they were meant to arrest your eyes as you walk down the street and then slip into your subconscious. They’re colorful, they’re bright, they’re eye-catching. They were made to attract your attention—to excite something in your brain and pass their message on to you. And they were made to look good, which is diametrically opposite from contemporary art.”

A history major on the Hill (his mother, Judith Cohen Lowry ’56, is a Cornellian), Lowry also studied communication and represented the Big Red in speech-and-debate competitions as a member of the forensics team, which he calls good training for his current career. He lived in Prague for four years after graduation, eventually joining the family business in the mid- to late Nineties after a variety of professional forays, including working for a New York political campaign. “I tried to do everything else I could before I settled on this,” he says with his trademark dry wit, “just to prove to my parents that I wasn’t interested.” Lowry’s personal collecting zeal is for posters from Czechoslovakia (where his father was born) dating from the 1890s to the 1970s. He and his dad have more than 1,000 between them—a trove sufficiently distinguished that two years ago, the National Czech & Slovak Museum & Library (located in Cedar Rapids, Iowa) mounted an exhibit of some three dozen devoted to travel. “We like to say it’s the largest collection in the world outside the Czech Republic,” he says with a smile. “Which is impossible to quantify.”

ANTIQUES ROADSHOW for WGBH, (c) WGBH 2018

Lowry’s “Roadshow” travel season runs for a few months each year, on spring and summer weekends; this year, the show visited a total of five cities (in Florida, Oklahoma, Kentucky, California, and Michigan). Shooting days can stretch past twelve hours, with Lowry and his fellow experts often gathering for dinner and libations afterward. (“If it were golf,” he says, “it would be the nineteenth hole.”) As Lowry notes, the appraisers not only volunteer their time, they cover their own transportation, lodging, and some meals (breakfast and lunch are catered on shooting days). “The show has a very large, very talented, entirely free labor pool,” says Lowry, one of several Swann experts who regularly appear on the show. “It’s worth every penny to us, because whatever few thousand dollars we spend traveling is returned in spades in the form of publicity, recognition, and credibility. It’s helpful that it’s on PBS and not Bravo, like one of the ‘Housewives.’ People trust PBS—it’s the gold standard—and as a result trust all of us for being on the show.”

Among the skills that Lowry has honed over the years is the art of letting people down easy; after all, of the thousands who come to each taping with heirlooms in tow, only a small fraction have genuine treasures. “Everyone thinks that what they have is worth something,” he says. “You don’t want to tell a little old man or a little old lady, ‘This rare Incan object is a modern Mexican forgery and it’s worth $10,’ and watch as their life’s dream floods out of their body. The inherent risk of doing something like that in front of the camera is that you become nationally known as the ‘dream crusher.’ ” The most common refrain from guests, he says, is that the item in question was bequeathed by their grandmother, who told them to keep it, because someday it would be valuable. “When we’re doing the show, I must hear it seventy times a day,” he says, “and it has never been true—never once—at least in the paper world.”

Among Lowry’s most vivid “Roadshow” memories is one from his first year on the program: During a stop in Richmond, Virginia, a woman came in bearing a paint-by-numbers version of the Mona Lisa. Lowry, who was still learning the ropes, watched in awe as a colleague talked up the original painting’s priceless nature, its place of honor in the Louvre, and the genius of Leonardo da Vinci—and the guest left happy, satisfied to own a one-of-a-kind reproduction of a classic work. “We get a great deal of turn-of-the-century religious iconography; they’re beautiful, they’re common, and they’re worth about $75,” he says. “It’s up to us as appraisers to evoke our best bedside etiquette and say, ‘Your grandmother must have loved you to leave you something so precious. On the open market, the actual monetary value wouldn’t come anywhere near the emotional value—but if you were to try it sell it, you might get $75.’ ”

Lowry observes that, thanks to the advent of the Internet, the drama of “Roadshow” has changed over the years. When the show began, he says, laypeople had few resources for researching an object’s background and potential value. “You could find an old piece of paper at a flea market and have no idea what it was; if you wanted to know what you had, you really needed an expert,” he says. “Now, you can find 85 percent of what you need to know online, and that means that discoveries have become slimmer on the ground. Before it was about discovering great stuff; now it’s about finding great stories—posters that had been pulled out of the dumpster or were bought at flea markets because they were attractive, but nobody knew that they were $20,000 pieces.”

Lowry conducting a sale at Swann Auction Galleries.Provided

In addition to his “Roadshow” duties, Lowry conducts many of the auctions at Swann, as well as at charity events in and around New York. He also trains the auction house’s staff in the art of wielding the hammer—offering guidance on topics such as keeping the audience’s interest throughout a sale that may include hundreds of lots, and the basic importance of pronouncing the artists’ names correctly. “You’re taking bids from four different places—in the room, on the phone, and online, as well as bids that have been left in advance—so you have to keep your head about you,” he says. “It can be a lot of fun. It’s something I enjoy doing tremendously.”

Even in the Internet age, Swann distributes handsomely printed catalogues for the roughly forty auctions it conducts each year, for which bidders come from as far away as Europe and the West Coast. (An annual subscription to the catalogues—which some consider collectors items in themselves—costs $550 for U.S. clients, $650 for international mailing.) The day before Lowry sat down with CAM, Swann had held an auction of nineteenth- and twentieth-century literature, including rare or first editions of works by such authors as Ray Bradbury, Raymond Chandler, Stephen King, Ernest Hemingway, Mark Twain, Leo Tolstoy, and George Orwell. That morning, staff were transforming the auction room into a display gallery for the following week’s sale of contemporary art, featuring the work of Andy Warhol, Sol LeWitt, Alexander Calder, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and more. “One of the reasons it’s so easy to love this job is that every week it’s something else,” Lowry observes. “The imagery is changing constantly. It’s a never-ending parade of interesting material, people, and stories. It’s fabulous.”

My husband and I, Cornell alumni, traveled to France for over 20 years. One of our favorite places was Le Château Nieuil in the Charente region. M and Mme Bodineau, the owners, have a collection of old posters that is mind-boggling. Unfortunately, they keep the posters in a damp cellar. There are probably hundreds of them, some probably rare and valuable. As guests, we felt that criticizing their storage practices would be rude, but I often thought that Mr. Lowry would love to dig into these posters. Now that I know he is a Cornell alumnus, I decided to write.

This was a wonderful article about alum Nicho Lowry. Now my husband and I understand Mr. Lowry’s wardrobe choices… much like his description of what a poster was meant to do. It also gave us insight into one of our favorite programs.