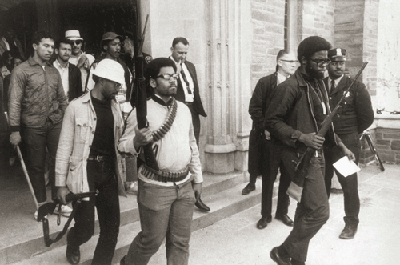

In a photo that won a Pulitzer Prize, Eric Evans ’69 (center) and fellow members of the AfroAmerican Society exit the Straight.Steve Starr / AP Wide World

It might have been just another protest, another takeover of a university building in the turbulent Sixties. If it weren’t for the guns.

On the afternoon of Sunday, April 20, 1969—Parents’ Weekend—a group of African American students emerged from Willard Straight Hall after a two-day occupation. An Associated Press photographer named Steve Starr was there, and he captured an image that would win a Pulitzer Prize: a group of young black men exit Cornell’s student union toting weapons. The Straight, a Gothic fortress of a building that seemed to embody the proverbial ivory tower, provided a powerful symbolic backdrop. But the thing that clinched it—the factor that, arguably, earned Starr his Pulitzer—is the man at the center of the photo.

The students on either side of him are carrying their rifles with one hand wrapped around the stock, their eyes cast slightly downward; considering that they’re armed, their mood is relatively non-threatening. But the image of Eric Evans ’69, one of the leaders of Cornell’s Afro-American Society (AAS), delivered a different message—one that announced that black militancy had come to Cornell, that the campus and perhaps higher education itself would never be the same. Evans is holding his shotgun straight up in a pose of victory, his finger an inch from the trigger. Snaked around his waist and shoulder is a bandolier studded with ammunition. His head is held high, his expression steely but placid. “Oh my God,” Starr reportedly said before he snapped his famous picture, “look at those goddamned guns!”

It was forty years ago this spring that black students at Cornell conducted the first-ever armed occupation of a building on an American campus. It wasn’t, despite the common misconception, an armed takeover; the guns were smuggled in after the Straight was occupied, in response to an incursion by fraternity brothers from Delta Upsilon who tried to oust the black students. Whether the occupation was a brave act of conscience or a crime that merited punishment was deeply controversial at the time, and its legacy continues to be a matter of debate. Many see it as a watershed event in the battle for civil rights on the Hill and elsewhere; others call it the beginning of the end of academic freedom.

To mark the takeover’s fortieth anniversary, Cornell Alumni Magazine caught up with some of the key players in the events of spring 1969 and its aftermath: AAS leaders Tom Jones ’69, MRP ’72, and Homer “Skip” Meade ’69; AAS member Andree-Nicola McLaughlin ’70; student government leader Art Spitzer ’71; professor emeritus Walter LaFeber, then head of the history department and a vocal member of the faculty; former Cornell Alumni News editor John Marcham ’50, who covered the events extensively; and University of Wisconsin professor Donald Downs ’71, who observed the events as a student and went on to write Cornell ’69: Liberalism and the Crisis of the American University.

Those who were students during the takeover have taken divergent paths. Jones—who, in a radio interview, infamously threatened several faculty members and declared that Cornell “has three hours to live”—went on to become head of the nonprofit workers’ retirement fund TIAA/CREF and a Cornell trustee; he now runs his own private equity firm in Stamford, Connecticut. (In 1995, he endowed the Perkins Prize for Interracial Understanding in honor of former President James Perkins, who was widely derided for his handling of the unrest and resigned at the end of the school year.) Meade and McLaughlin both earned PhDs and went into academia, she at Medgar Evers University and he at the University of Massachusetts. Spitzer, an attorney, is director of the ACLU’s Washington, D.C., office.

Speaking just days after the inauguration of America’s first black president, they pondered the tumultuous times on the Hill in the late Sixties, as well as the legacy of the takeover at Cornell and beyond. Even four decades later, some facts remain murky. For example, while both Downs and Marcham are convinced that the cross burned outside a black women’s residence that spring—a factor in catalyzing students to take over the Straight the following day—was in fact the work of African Americans trying to stir up sentiment, McLaughlin strongly disagrees. Even the precise number of students who occupied the Straight is unclear. In his coverage immediately after the takeover, Marcham reported it to be “some 50-100.” The 1970 Cornellian said it was 110. Downs pegs it at around eighty, and Jones recalls it was about 120.

Although the takeover is commonly claimed as the catalyst for the formation of the Africana Studies Center, its establishment was not one of the seven terms of the agreement hammered out between the Cornell administration and the AAS to end the occupation; in fact, trustees had approved funding for the center the previous week. As President Emeritus Dale Corson (then provost, he was intimately involved in the administration’s response) noted in an essay in the Cornell Chronicle on the takeover’s twentieth anniversary in 1989: “The program was in place and a director had been recruited months before the Straight takeover. I know of no aspect of the program that grew out of the Straight incident. All the takeover did was make it difficult for us to deal with our various university constituencies.”

More than any single event before or since, the takeover polarized Cornellians. Particularly among the faculty—who agonized over whether to punish the occupiers in an era when the campus mood was highly volatile and expulsion could mean being drafted to Vietnam—it caused personal rifts that, in some cases, never healed. Outraged that the AAS students weren’t punished for their actions—in addition to taking over the Straight and stockpiling firearms, the occupiers damaged property and brusquely ousted more than two dozen visiting parents from their bedrooms—some alumni severed ties with the University, refusing ever to attend Reunion or donate money. But as Marcham notes, alumni giving actually went up immediately after the takeover. While some Cornellians saw the upending of the established order as the death of the alma mater as they knew it, others embraced it as the dawn of a new era of equality, with Cornell in the vanguard.

In a view from Olin Library, AAS members march toward the temporary Africana Center.Carl A. Kroch Library / Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections / Cornell

TOM JONES: I was in the Class of ’69, so I came to campus in the fall of 1965. That was a short while after Dr. King’s march on Washington in 1963. In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act. Then, in 1965, the Voting Rights Act was passed. The mood was one of being in an era where important things were happening, and where others were making enormous personal sacrifices to fight for freedom and equality. It looked like the black community was beginning to achieve significant breakthroughs. My class was the first with a substantial number of black students. And by substantial, I mean there were thirty-five.

ANDREE-NICOLA MCLAUGHLIN: People were not ready for our presence, and that was made known repeatedly by fraternities and sororities excluding students of color from social events. We had professors or instructors who openly advocated racist concepts like eugenics. We also met a lot of apathy or ignorance on the part of Cornell’s administration. They didn’t know how to deal with a diversifying student body. It was like many of the colleges and universities at that time. They accepted students of color, but they didn’t know what was required to make the campus comfortable for them.

JONES: There wasn’t one experience. I had come from a highly educated family; my father was a nuclear physicist as well as an ordained minister and my mother was a school teacher. I had lived in integrated communities. But there were many black students who had very uncomfortable experiences. Not always malicious; I remember incidents where black girls were doing their hair in the dorm and the police being called because people thought they were smoking marijuana, because of the smell. White people just weren’t accustomed to that. It’s an innocent mistake in one sense, but on the other hand, it’s one of the reasons why some black students wanted a place that was a relief from those kinds of interactions. I did not personally have a lot of grievances or complaints. But as each year went by, I felt more and more that I had a duty to be part of this larger fight.

By 1969—with the war raging in Vietnam and the battle for civil rights in full tilt—campus unrest was hardly new to American universities, Cornell included. As early as 1965, protesters had disrupted a speech by Averell Harriman, then U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam. In the spring of 1968, black students took over the economics department to protest allegedly racist teachings by Father Michael McPhelin, a visiting lecturer. That December, demanding an autonomous black college, protesters held a sit-in in Perkins’s office, among other actions.

JOHN MARCHAM: I was struck by how quickly the campus broke apart and how everyone realized it had been a gentlemen’s agreement under which the University had run. You could feel that the place was gradually losing its ability to do anything. A student would get up and interrupt a speaker and a committee would say, “This is heinous. You’re the last student who’s going to not be disciplined for doing this.” And the next one would be the same. The faculty just didn’t have the stomach for this stuff.

WALTER LAFEBER: The student politics leading up the occupation were the kind where the farther out you were, the more likely you were to maintain control. The more extreme elements were increasingly taking over in both the African American and white student movements—which made them less rational, more driven by personal relationships, and more threatening to the kind of rational discourse that should be conducted at a university. You could see that discourse becoming unraveled.

In February 1969, in the most shocking incident to date, Perkins was removed from the podium and physically shaken by two AAS members during a symposium on South Africa in Statler Auditorium. LaFeber recalls speaking to the president that evening.

LAFEBER: I said, “What happened to you tonight was quite horrible and shouldn’t be allowed. What are we going to do about it?” Perkins said, “I don’t think we need to do anything. This will all work itself out.” He refused to do anything to the students. I think one reason was because if he tried to bring them to account, there would have been an explosion. I came away thinking that there was no longer any limit as to what might happen. Perkins had misjudged, if not lost control of, the whole situation. I go back to that conversation as the point at which I realized that this was going in a direction that was not good.

As the semester unfolded, the students involved in the December protests faced disciplinary action, but refused to participate. In March, when the University declined to punish white students who had disrupted recruitment by Chase Manhattan Bank in Mallott Hall to protest its business with South Africa, it was seen as a racist double-standard. Campus unrest surged with assaults on three white students, allegedly by African Americans, and the burning of a cross outside Wari House, a residence for black women. At about 5 a.m. on April 19, the first AAS members entered the Straight.

JONES: To be totally honest, I was not in favor of taking over the building. We voted, and the majority thought it was necessary to do something that would shock the University, grab its attention. Parents’ Weekend would be a perfect time. The Straight was a good target.

MCLAUGHLIN: Most of us didn’t know where we were going. Only key people in the leadership knew what was going to happen. So we got in there, and we were excited. Willard Straight Hall was our social hub—that’s why it was strategic. The University would have to deal with our issues, because they couldn’t function without that hub and it was Parents’ Weekend. On a practical level, most of us saw this as a short-term action, taken while parents were there, to get the administration’s attention, and that it would be resolved in a matter of hours or days.

ART SPITZER: It came as a complete surprise to almost everybody. There were rumblings of dissatisfaction by African American students. There was controversy on the pages of the Sun. But the vast majority of students were going about their lives, dealing with their problems—academic problems, boyfriend and girlfriend problems, all the usual stuff—or being happy. I don’t think most people were aware or gave much thought to all this.

JONES: I think I could’ve sat down with President Perkins and, in short order, worked out the specific issues on campus in a mutually satisfactory way. But there were elements within the black student community who rightly felt, “No, this is a symbolic element of a bigger battle.”

The occupying students tussled with employees and took over WVBR; the station would eventually broadcast from downtown Ithaca. Visiting parents sleeping in the Straight were ousted from their rooms in the early hours, some forced to leave with nothing but their nightclothes.

SKIP MEADE: There was a delegation of responsibilities. One of mine was security, trying to make sure that the doors to the outside were secure. There were some early sections of the New York Times bound by bailing wire, so I used it on the doors. I was never with the group. I was constantly moving around, checking to see that things were secure.

JONES: At first, it was kind of fun. Then the guys from Delta Upsilon came in. I was playing pool and I heard this commotion. I went to see who it was, and here were some frat boys who had decided they were going to throw us out. Something clicked inside of me: “This cannot end this way. Not with some frat guys deciding they’re vigilantes.” I went up to the first guy and I punched him. There was a fight, and we threw them out. After that, the atmosphere changed, because now there was an element of “Are they going to come back with more people? Are the police going to do something?” That ultimately led to the decision to arm ourselves for self-defense.

With the help of activists from Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the AAS had been purchasing rifles from local gun stores throughout the semester. After the Delta Upsilon incursion on Saturday morning, students smuggled the guns into the Straight through a back door. Unarmed campus security officers, under orders to allow AAS members and supporters in and out of the building, let them through.

MEADE: When morning came, and there was recognition that we were armed, it became important to begin the negotiations in earnest. But it was clear that our demands were not being received and that the administration was not going to risk having armed students stay in the building one more night. So that meant we’d have to be expelled, and we would try to repulse the attack. And so, for me, it came to be fairly obvious that this might be my last day.

JONES: I grew up going deer hunting. I had been in ROTC. I knew how to handle a rifle. Some of the other students, especially those from rural backgrounds, had some familiarity with weapons. But there were others who didn’t. That was cause for concern. There’s always the risk of an accident. Somebody doesn’t have the safety on. Somebody trips and falls and the gun goes off. Crazy stuff can happen.

DOWNS: Cornell became this cauldron of rumors. A lot of it was uncertainty and incomplete reports, trying to figure out what’s real, what’s actually happened, feelings of amazement. We had been hearing about people around town coming to campus with guns. One person told me his fraternity was starting to bring guns in from home. We were all thinking, How can this be happening? What does it mean?

As Downs reports in his book, “Hysteria, fear and paranoia raged through campus.” He describes how Cornell, located in a small, isolated town, was more affected by the unrest than an urban campus would have been. “At Columbia and Berkeley, large surrounding cities absorbed the tensions, alleviating potentially overwhelming pressures. Cornell’s setting led to the opposite effect: a magnification of tensions and fears. There was no escape.”

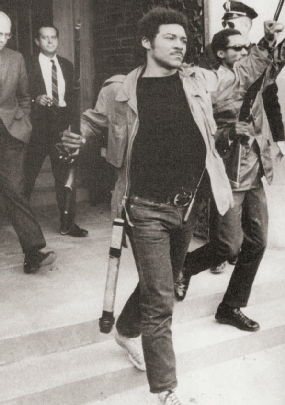

Tom Jones ’69 took the symbolic position of being last to leave the Straight.

Starr / AP / Wide World

MARCHAM: There was an unreality to what was going on. In the anti-war movement there was a lot of guerilla theatre and people exaggerating points and making ad hominem attacks on administrators. When the event took place, one of the things that struck me was how much everyone on campus depended on WVBR for coverage. It was absolutely amazing. They broadcast every hour on the quarter hour, and you could see the community was stuck to that, keeping track of what was happening.

JONES: I’m proud of the courage of all of those black students who didn’t crack, who didn’t succumb to the fear of what might happen. There could be a massive assault against us. People understood that, if that happened, it would change Cornell forever—it would change America. It would be a historic event. I’m proud that we stayed together when there was no personal gain to be had. I’m proud that so many white students said, “We’re not going to let these black students stay isolated. We’re going to rally and create a buffer between them and the police.”

SPITZER: Students were not hardliners the way some faculty were. There was a general feeling of support and sympathy for African American students. It was a liberal time politically, so the student sentiment was that punishment was the wrong idea—that we should be mending 200 years of oppression, not continuing it.

JONES: I felt like the wheel of history had spun around and the dial was pointed at my generation. If I had been born in 1925, I would’ve hit the beach at Guadalcanal because it was my duty. If I had been born in 1845, I would’ve crossed the field at Gettysburg. I believed in the fight.

As white students gathered outside the Straight in support of the AAS, administrators negotiated with the occupiers. Eventually, they came to an agreement that included amnesty for those involved in the takeover and investigations of the cross-burning incident and the Delta Upsilon incursion. The Cornell negotiators made a concession that would have enormous symbolic consequence: when the AAS members refused to exit unarmed, the administrators didn’t insist that they leave their guns behind. It set the stage for one of the most enduring, and unsettling, images in Cornell history.

JONES: It was a moment of enormous pride. Some of the black students, particularly those from southern and rural backgrounds, had never stood up to white people in their lives. I intentionally took the position of being the last to leave the building, because I wanted that symbolism to reflect what I felt, which was 100 percent commitment. Even though I had not thought it was a good idea to begin with, once we’re in it, I’m committed. This is my fight and I’ll see it through to the end.

DONALD DOWNS: I was standing outside the Straight when the students came out. It was surreal to see them walk out with the rifles, with the bandoliers across their chests. It was a stunning experience. Part of me admired what was going on. They were standing up for what they believed, taking on authority in a big way. But the other part of me was saying, “What can this lead to? Are things going to fall apart? And is this something that should be taking place on a campus? Aren’t universities supposed to be places of reasoned disagreement and pursuit of truth?”

JONES: It not only shocked Cornell, it shocked the country. I believe it’s one of the reasons this country decided to try to fully incorporate all of its citizens, whatever racial or ethnic background.

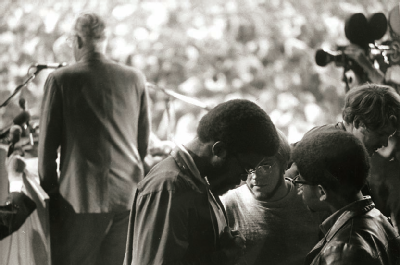

In a much-anticipated speech to a packed Barton Hall, President James Perkins astonished and appalled his audience by failing to specifically mention the takeover.Carl A. Kroch Library / Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections / Cornell

Though the occupation was over, it was just the beginning of an intense week on the Hill. As the faculty held tortured debates over whether to nullify the pact with the AAS and punish the participants, thousands packed Barton Hall for speeches and teach-ins. Jones’s inflammatory rhetoric on the radio had some professors scared enough to leave their homes and move into motels. Rumors flew about which building might be occupied next, as news of armed deputies mustering downtown sparked fears of more violence.

SPITZER: Thousands of people on campus realized there was a crisis going on and wanted to know more about it and get involved. A fair amount of that feeling was fear and opposition to the idea that the state police and sheriffs were going to try to solve the problem their way. There was a widespread feeling that would be a terrible thing. We didn’t want rural deputy sheriffs coming onto campus dealing in an unfriendly way not only with African American students but with the whole student body, whom they presumably viewed as a bunch of long-haired, pot-smoking hippies—which we were.

DOWNS: There was a real concern that it was going to go to the next level, which could really be chaotic. We had heard Tom Jones on the radio, so it was like a pressure cooker. There was concern that this could lead to something scary.

JONES: Words have power. They have a purpose. When I used words like “Cornell has three hours to live,” it was a metaphorical statement. Because if violence erupted, it would have been the end of Cornell as we knew it. The University never would have recovered from the disgrace of bloodshed on campus. I think it would have marked Cornell even more deeply than Kent State came to be marked by the deaths that occurred there.

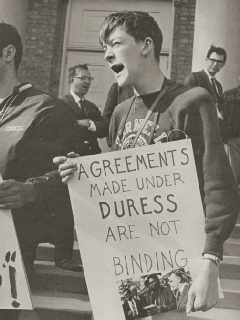

A student urges the faculty to reject the deal between Cornell and the AAS.Cornell Daily Sun

Eventually, the campus calmed down. In a decision that prompted a few resignations and much lingering resentment, the faculty opted to accept the agreement with the AAS, some out of fear that events would spiral out of control if they insisted on punishing the occupiers. With many professors deeply disillusioned with Perkins, the writing was on the wall; at the end of the semester, he resigned and Corson became president.

JONES: I’m not proud that an implicitly violent act was used to settle a dispute, when that’s counter to everything that the University stands for. I’m certainly not proud that President Perkins became a scapegoat for the rage that erupted. He was a good person and that is the tragedy of these things. Sometimes it’s the good people who end up suffering the most. Wars and human conflicts have a lot of innocent victims. Many of the black students never recovered and many of them never finished at Cornell. These things take a toll.

DOWNS: The students got everything they wanted, pretty much, and went off and did their own thing. And so the racial segmentation that had existed before reasserted itself. The average white student, speaking generally, went his or her way. The black groups went their way, and some black students had a foot in both worlds. But there were certain things you had to be careful about saying aloud in public. You didn’t want to say something too politically incorrect because it might get you in trouble or raise these kinds of tensions again.

LAFEBER: The wounds continued to fester for more than a generation. At the 1999 commemoration, I was struck by how current many of the remarks were. There were still recriminations and hard feelings. Some faculty relationships were broken in ’69. People quit talking to each other. Some of them never began again. I think those were the exceptions, not the rule. But the faculty did divide, because the issues were fundamental. If you were going to take a position for academic freedom, then you were essentially saying no to the people who occupied the Straight. The faculty felt intensely about it, because we were going to have to stay here long after the students who were doing the protesting would leave. We were going to have to live with the consequences.

DOWNS: I think there were two effects—one good, one less so. The good is that it opened up the University to minority students. The civil rights movement moved into higher education and Cornell was a pioneer. On the negative side, it was the beginning of the politicization of universities, in which groups with certain political and moral agendas started pushing them in a way that could conflict with the intellectual mission of the university, which is the pursuit of truth and encouraging as many viewpoints as possible. In some ways, it was a harbinger of the culture wars that came to universities in a bigger way beginning in the Eighties, like speech codes.

MCLAUGHLIN: Our parents and communities expected us to reap the benefits of the federal civil rights legislation, to be trail-blazers for opportunity, but even though the laws had changed we were still confronting the mindset of racism and inequality. It was a hostile environment. That experience traumatized a number of students of color. Some of us became professionally successful, but it doesn’t mean that it didn’t have an emotional cost. It looks victorious now—and yes, we have a stellar Africana Studies and Research Center. But nobody really discusses the emotional costs.

JONES: Was every decision right? No. It’s like being in the fog of battle. Stuff happens and you make decisions on the fly. You do the best you can and all you’re thinking about is, we’ve got to win.

McLaughlin, who attended the Democratic National Convention in Denver, went to Washington for the Obama inauguration. Taking refuge from the cold, she witnessed the swearing-in on a big-screen TV in a packed restaurant with an “intergenerational, multicultural crowd.”

MCLAUGHLIN: It was one of those pivotal moments, and I equate it to my participation in the Willard Straight Hall takeover. I was part of something bigger than myself. Some call it history; others may call it the struggle for human dignity.

JONES: Frankly, I do not think Barack Obama would be president today without what we did in Willard Straight Hall in 1969. I believe Barack Obama stands on our shoulders. The Straight was part of a series of historical events that began with Rosa Parks in 1955 and continued through the Sixties with the Freedom Riders and the marchers at Selma, Alabama, and made possible this magnificent thing that happened in January 2009. I think we’re part of a chain of history. I’m not saying the most important part, but we’re one of the links.