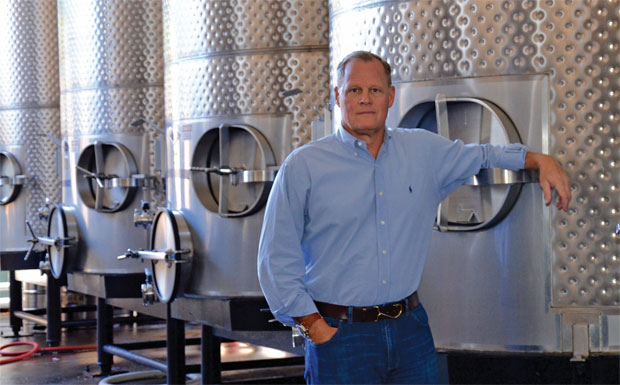

John Wilkinson ’79 with some of Bin to Bottle’s 170 tanks.

In the early Nineties, after developing luxury hotels in San Francisco and elsewhere, John Wilkinson ’79 moved to California’s Napa Valley—and, as he recalls with a chuckle, in that setting it would have seemed downright bizarre not to get involved in the wine world one way or another. “It’d be like living in Silicon Valley and not being in high tech, or living in Hollywood and not being in entertainment,” says the Hotelie. “It just feels wrong.”

Wilkinson planted a vineyard on his land—three acres of Syrah and Merlot—and started making wine at home. Eventually, he says, “I realized I was outgrowing my garage”—and around the same time, he spied a business opportunity. His friends in the winemaking industry weren’t thrilled with the service at local custom crush facilities—places that offer the equipment and expertise to turn harvested grapes into Dionysian delights. “No [winery] really wants to be in the custom crush business; they want to be making their own wine,” Wilkinson says, explaining that custom crush is often a sideline business to generate income while wineries build their brand. “There’s an inherent conflict of interest,” he says, “because their fruit is more important to them than the client’s is.”

Grapes fresh from harvest and ready for processing.

So, in 2005, Wilkinson and his partners launched a dedicated custom crush operation, dubbing it Bin to Bottle. Today, its sixty-five or so clients range from modest producers to wine-industry darlings; they include Dave Phinney, founder of the highly regarded label The Prisoner, and Steve Matthiasson, whom the San Francisco Chronicle named its 2014 winemaker of the year (and who, in a testimonial, calls Bin to Bottle “a godsend”). “All we do is make wine for others; that’s what sets us apart, because everyone is as important as everybody else,” says Wilkinson, who regularly hosts interns from CALS’ enology and viticulture program (where his son, Max, is a junior). “It’s very democratic. We process the fruit in the order it comes in, so everyone feels they’re getting a fair shake.”

The business has grown steadily, Wilkinson says, from processing 700 tons of fruit its first year to some 3,000 now; he notes that in 2015, Bin to Bottle had to turn away 1,500 tons more. So the company is expanding: it recently acquired a winery fifteen miles away, where it aims to process an additional 500 tons annually, and another production facility is in the works next to its Napa headquarters. “We’re amazingly customer service driven; our goal is not to say no to anything,” says Trevor Chlanda ’03, assistant director of winemaking, who has been at Bin to Bottle since 2013. “We’re here to make sure a client’s wines are taken care of exactly as though this were their winery and we were their winemaker. To do a good job, you have to have that sense of ownership.”

Bin to Bottle’s name is literal: grapes arrive in giant crates before being dumped into a machine that de-stems the bunches and separates out unripe fruit. Then a thick hose shoots the grapes into large plastic boxes—in the case of some Merlot that came in one morning last fall, they’ll spend five days wallowing in dry ice to coax maximum color from the skins—before the juice makes its way to one of the facility’s 170 stainless steel tanks, where the fermentation process is carefully monitored and tweaked.

An elevated pH? Add tartaric acid to bring it down. Yeast not active enough? Gently turn up the heat to give it a boost. Too much sugar? Add some water to lower the percentage. “As you gain experience, you start realizing where the wine is going to go—what the oak’s going to do to it,” says Wilkinson, offering a thick, bready, slightly effervescent sample from a tank of Zinfandel that’s only been fermenting a day or so. Before reaching its final destination—the bottle—the wine will reside in the aging facility next door, where barrels are stacked high in imposing rows and the temperature is controlled by a solar-powered cooling system. “There are about 9,000 barrels in here,” Wilkinson observes. “It’s a little like the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark.”

| Drink Up In addition to Bin to Bottle, Wilkinson is a partner in several other libation-related ventures: |

Wilkinson with samples used to blend Straight Edge’s whisky. Team Building Total Adventures hosts corporate events centered around blending wine. Participants get a primer on the process; then, in small groups, they create a blend from four red varietals. A panel judges the results, and everyone goes home with a bottle of the winner. High Spirits Wilkinson got into the liquor business with a blended whiskey called Slaughter House, which won gold at the 2015 Whiskies of the World competition. Splinter Group Spirits also makes Straight Edge Bourbon; a rye is in the works, with plans for tequila, rum, and gin. ‘Blush’ Wines Slo Down Wines challenges enology’s highbrow image by cultivating a cheeky air. Its flagship product, the Syrah blend Sexual Chocolate, raised its profile with risqué videos suggesting it be enjoyed in circumstances best described as “not safe for work.” |