(Continued)

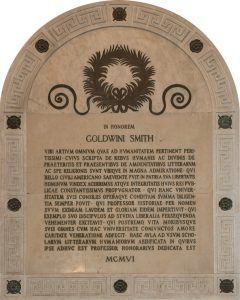

WORDS TO LIVE BY: A plaque in Goldwin Smith Hall offers a paean to its namesake. It reads: “This magnificent building, built to house courses in the humanities, and in which the honoree himself is still an professor ex officio, has been dedicated in honor of Goldwin Smith, a gentleman very well versed in all the arts that pertain to the human condition / Whose writings about matters human and divine, about the past and the present, about the joy of literature and the hopes afforded by religion, are universally admired / Who, amid the ravages of the American Civil War, was a fierce abolitionist and a staunch defender of the integrity of this country / Who has constantly supported this university, which was established by his advice and efforts, with the greatest care / Who by his name, as professor of history, has brought this university great accolades and glory / Who by his own example deeply inspired students to study the liberal arts / And, lastly, who, by his life and character fostered love, charity, and devotion among everyone associated with this university.”Jeff Lower

Gallagher himself came to the language relatively late; he began studying it as an undergrad at the University of Michigan, where he majored in microbiology and graduated in 1993. He didn’t fall in love with Latin until he moved to Rome to study philosophy and theology as a seminarian and encountered a legendary Vatican Latinist and teacher who’d long encouraged a more active approach to learning the language. After ordination, he returned to Michigan to serve as a parish priest and teach at a seminary before being tapped to succeed his Latin mentor as a Vatican secretary. “Latin for me has this beautiful music—not just the sound but the feel to it, the way it’s constructed, almost like a Beethoven or Mozart symphony,” he says. “It’s the ending of words that indicates the meaning, not the word order, so when you’re speaking or writing you have a lot of freedom on how to arrange words so they sound appealing—but also to syntactically separate words, so your listener has to be patient, like listening for a theme in Beethoven to develop.” In addition, he says, “when you learn Latin, whole worlds open up. It can be physics, astronomy, medicine, history, philosophy, theology. You can read Galileo’s discovery of the moons of Jupiter in flawless Latin. Basically, the whole of human experience is opened up to you through the lens of a language.”

Both Gallagher and Fontaine are proponents of teaching and speaking Latin as a living language, an approach they say is all but unheard of in American colleges and universities—a program at the University of Kentucky being a rare exception—and one that makes Cornell unique in the Ivy League. While both professors are passionate fans of classical texts, they believe that the ability to speak fluently is invaluable—not only offering its own pleasures, but enabling closer and more active understanding of the written word. “This idea of learning Latin through the spoken method is not a gimmick,” says Rawlings, who helped recruit Gallagher to the Hill while serving as interim president. “This is to help you learn it well, so that when you read Cicero or Virgil or whomever, you understand it better.”

The Tweet LifeTranslating the Pope’s Twitter Feed

|

Gallagher came to Cornell from the world’s Latin epicenter, the Vatican, where it remains the official language. As one of the Pope’s Latin secretaries, Gallagher passed the Sistine Chapel on the way to work every day. He and a half-dozen colleagues were responsible for translating everything from weighty diplomatic tracts to the Pope’s Latin Twitter feed. Each afternoon, he recalls, the staff would gather for tea and conversation. “We would talk in Latin about the weather, the soccer game the night before—everything from the World Series to the World Cup—and it could be a real challenge,” he says. “To talk about, say, a car accident you were in, you’d have to think hard about the vocabulary. But we forced ourselves to do it, so we could get better, and also to stay speaking in the same language in which we were working.”

For Fontaine, a memorable translation of a modern term came during a summer teaching stint in Rome, when he was called upon to come up with the Latin for “selfie stick.” He coined the phrase ferula narcissiaca, or “Narcissus stick.” “I must say with no humility that it was regarded as fairly ingenious,” he says with a laugh. “It went viral all over Twitter.” In addition to his teaching, Fontaine regularly consults—gratis—with museums who need help translating the Latin in their artworks. Once, he even helped a collector identify a forged painting by pointing out a mistake in a Latin abbreviation. (Among his other sidelines: running a now-defunct website, latintat.com, that offered free—and more to the point, accurate—translations for people aiming to get tattooed with Latin sayings.) Rawlings notes that having both Fontaine and Gallagher on the faculty makes the University “especially lucky” when it comes to spoken Latin. “The fact that Cornell has these two professors, and they’re young and exuberant, puts it in a unique position,” he says. “And that is well known across the country.”

Latin has had a role at Cornell since its early days; the entrance exams that nineteenth-century students had to pass to gain admission to the University included a Latin section that often featured not only translations and grammar, but ancient geography, Roman history, and more. (From the 1878 test: “When did the Lupercalian and Saturnalian festivities occur? Upon what modern observances have they probably been grafted?”) But as Fontaine notes, the campus itself contains only a smattering of Latin inscriptions, including a brief one in the lobby of Willard Straight Hall and a longer dedication to Goldwin Smith in his namesake building. “This tells you something about Cornell,” he says. “Every other Ivy is loaded with Latin inscriptions, because they were Bible colleges—and Catholics, Protestants, and Anglicans all used Latin as the basis of their scripture. But Cornell was founded as a secular, co-educational, ‘any person, any subject’ place from the get-go, so it doesn’t participate in the Latin tradition. The absence of Latin shows you Cornell’s commitment to secular education from the beginning.”

The University’s outward lack of Latin notwithstanding, it has—particularly with Gallagher’s arrival—become a lively locus of Latin scholarship. Andrew Hicks, a Medieval Latinist on campus, says the level of student interest is unprecedented in his seven years on the Hill. “It’s an extremely exciting time to be studying Latin at Cornell,” says Hicks, an associate professor of medieval studies, music, and religious studies. “It really has become kind of a self-driving, self-sustaining culture. There’s a new sense of urgency and value that comes from the students themselves.”

Fontaine says that after a dip in Latin enrollment during the economic downturn—when students may have felt increased pressure to pursue courses with more clear prospects for future employment—it has rebounded. According to figures from the classics department, more than 120 undergrads and grad students took Latin classes in fall 2017; in some semesters earlier in the decade, numbers had dropped as low as the sixties. “What has really come back with a vengeance is the enthusiasm,” says Fontaine, who is Cornell’s associate vice provost as well as a professor of classics. “The students are gung-ho about really learning it well. They’re especially interested in learning it as an active language, because it seems less like a code you have to crack and more like a language people actually use to talk to each other. Some of that is coming up from the high schools, because in the past ten years a revolution in pedagogy has been slowly growing, so we’re now getting e-mails from prospective students who know we’re trying to do this here.”

Fall 2017 saw the founding of the Sodalicium Loquentium Latine, a student-run Latin club that meets weekly in Stimson Hall’s Language Resource Center. The group, led by Nicole Marroquin ’19, offers such activities as playing games, composing poetry, and watching movies—all in Latin. “Some of my friends don’t understand why I would like a ‘dead’ language; they haven’t taken Latin and they don’t know the joy of reading exciting stories and learning about the history and culture of the time,” says Marroquin, a fluent French speaker who matriculated into the Engineering college but transferred to Arts & Sciences, where she’s double majoring in classics and in chemistry and chemical biology. “I hope the club will help strengthen students’ oral skills in Latin, because I think it’s tremendously helpful in translating and understanding the language. It might sound a bit cliché, but I think it brings it to life.”

For a decade starting in the mid-Aughts, Fontaine organized a similar effort, leading weekly Latin chats over pizza in Collegetown (first at the Chariot, then at the Nines) that would draw as many as a dozen and a half students. “The twenty-one-year olds would maybe get a pitcher of beer, because a little booze can free up the tongue,” Fontaine says with a laugh. “In fact, in the Odyssey, Homer says you’re less inhibited about public speaking if you’ve had a couple of drinks.” (Asked if the group raised eyebrows by conversing in Latin over pepperoni, Fontaine says, “I don’t think anyone ever regarded it as any stranger than anything else you’d see in Ithaca.”) Fontaine has also taught the Latin section of Cornell’s Foreign Languages Across the Curriculum (FLAC) program; a relatively new offering, it lets students earn one credit hour by meeting weekly to discuss topics related to an existing course—be it on history or politics or music—in a foreign language. The Latin FLAC that he led in fall 2016, he says, was one of the most popular in terms of student enrollment, behind only Spanish.

Both Fontaine and Gallagher are on the advisory board of the Paideia Institute, an organization devoted to the study of classical languages, and have taught in its summer program in Rome. Paideia has helped fuel a small, worldwide resurgence of interest in Latin, and counts numerous Cornell students among its alumni. “They had this uninhibited passion to speak Latin,” Gallagher says of the Cornellians he taught in Rome before coming to Ithaca. “I don’t know how to explain it, but I see it now that I’m here. They are fearless. They’re not embarrassed to come in and sound like babbling babies at the beginning. They’re very, very excited.” When it comes to Latin, he says, “Cornell is a very special place now. They’re aren’t many schools—Ivy League or not—that would be willing to give this a try.”

Here’s Translating You, ‘Kid’

A youth bestseller rendered in Latin

While still working at the Vatican, Gallagher was tapped for an intriguing side project: translating the mega-selling kids’ book Diary of a Wimpy Kid. In Commentarii de Inepto Puero, Greg Heffley is still having a rough time in middle school, from facing bullies to getting cast as a tree in the school play—but he’s doing it all in Latin. The concept wasn’t unheard of, as children’s works like The Wizard of Oz and Winnie the Pooh—even the first two volumes in the Harry Potter series—are available in Latin. “The more I read it, I realized two things,” Gallagher says of Wimpy Kid. “One, it was a great story—and two, it would actually render into really good Latin.”

While still working at the Vatican, Gallagher was tapped for an intriguing side project: translating the mega-selling kids’ book Diary of a Wimpy Kid. In Commentarii de Inepto Puero, Greg Heffley is still having a rough time in middle school, from facing bullies to getting cast as a tree in the school play—but he’s doing it all in Latin. The concept wasn’t unheard of, as children’s works like The Wizard of Oz and Winnie the Pooh—even the first two volumes in the Harry Potter series—are available in Latin. “The more I read it, I realized two things,” Gallagher says of Wimpy Kid. “One, it was a great story—and two, it would actually render into really good Latin.”

Scenes from the translated book in which the hero’s plot to knock another boy, Rowley, off his Big Wheel backfires; when Rowley falls and breaks his arm, the injury makes his popularity soar among the other kids at school.

The result, published in 2015, went into a second printing within months and landed on Amazon’s top ten list of foreign language bestsellers. In one of the editions, Gallagher includes an appendix explaining his choice of translations for certain terms unknown to ancient Romans—from “heavy metal music” (musica metallica gravis) to “Big Wheel” (Trirota Magna) to “Barbie Dream House” (Barbarae Aedes Optimae). “There are a lot of people who started to read it and got frustrated because it was too hard,” admits Gallagher, who launched the book at an event in Italy with author Jeff Kinney. “I knew that was going to be the case, because it’s not easy Latin but it’s a young person’s book. Some of the expressions I used, you’d have to have four or five years of Latin to really get.”

In Spain, there is a methodological revolution about the teaching of Latin. So, in many schools we apply the Live Latin method of Orberg. Therefore, it is very common to teach Latin in Latin, as we do with modern languages.

It’s sad that an Ivy League Classics Professor (and past university president!) with half a century of scholarship can openly laugh about his lack of mastery in his chosen field. We’re not talking about a completely reconstructed language; we’re talking about a language in which scholars were completely fluent (even conversationally) just a few centuries ago. I expect better from academia, especially at the highest levels.

In his saeclis obliviscentibus, videre artes antiquas recultas toto ex animo praegaudeo. Utinam sapientiae reciperatio etiam extemplo adveniat! Perdifficilius quidem est. Quantum laboris restat!

Latinis studebat in memoriam reducit praeclarum pede fabula! Nunc ad confidunt in genere Google interpretari quae habet facultatem ad transferendum loqui!

Implicit in the last sentence of the first paragraph is the view that if North Korea destroys cities cruelty is involved, whereas if the US destroys cities no cruelty is involved. This is offensive.