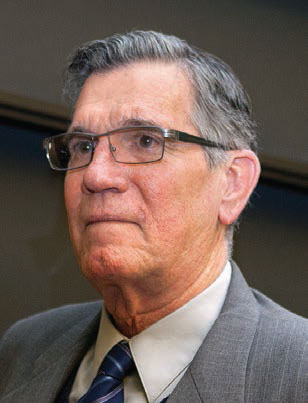

Big dig: Jorge de la Guardia, MEng ’74, has spent much of his career at the Panama Canal.

Imagine a floating barge 160 feet wide and longer than four football fields. Fill it with some 10,000 shipping containers—each about the size of a double-wide trailer—and send it across the Pacific, then squeeze it through the Isthmus of Panama by way of a three-chambered, mile-long lock system that raises the ungainly beast from sea level up eighty-five feet to a manmade freshwater lake. There it churns past similar vessels, fishing boats, and cruise ships filled with gawking tourists. As the barge approaches the Atlantic, the sequence is reversed, and the Panama Canal Authority rings up another hefty toll.

If all goes according to plan, by June 2015 the passage of these enormous “post-Panamax” ships will be business as usual on the expanded Panama Canal—an engineering project as enormous in scope as the original “Big Ditch” that opened in 1914. Seventy-three-year-old Jorge de la Guardia, MEng ’74, is executive manager for the $3.3 billion Locks Project Management Division, the centerpiece of the $5.3 billion overhaul. De la Guardia shepherded the project from design to planning and construction—a task he could never have imagined as a young man growing up in Panama. “To us as children,” he says, “the canal was just a given.”

As a youth, de la Guardia dreamed of teaching at the University of Panama, where he later earned an undergrad degree in civil engineering; a World Bank scholarship then brought him to Cornell. But the canal, not the lecture hall, would consume much of his professional career.

De la Guardia described his vocation in a campus talk last November, six years into working on the world’s biggest infrastructure job. He touched on the political and economic challenges of the locks project, then nine months behind schedule. “Overall, delays are to be expected on a project of this size,” he told an audience of more than 100 in the Plant Science Building. He pointed out that the international contracting firm building the locks was losing $300,000 a day and had a “$54 million problem.”

Jorge de la Guardia, MEng ’74

Blame it on bad cement. The new locks are made of steel-reinforced concrete that must resist moisture for up to 100 years; it took contractors six gritty months to get the recipe right. Other setbacks, including major storms in 2010, pushed the completion date from October 2014 to June 2015. All the while, maritime trade—and the ships that handle it—keeps growing.

It was the explosive rise in trade between Asia and the Americas that led to the construction of post-Panamax ships—those capable of ferrying upwards of 50 percent more cargo than the vessels, known as Panamax, that fit the current canal. “China is the main driver of the expansion—especially container traffic from the East Coast of China to the East Coast of the U.S.,” says de le Guardia. “The canal will be able to handle some of the biggest ships now being built, with the exception of oil tankers, which do not use it.” The Canal Authority earns some $4.5 billion per year, a substantial chunk of the nation’s GNP—and, thanks in part to a boom in exports of liquefied natural gas from the U.S. to Asia, revenues are expected to increase sharply.

Comparisons to other manmade wonders help put de la Guardia’s project into perspective: the new locks are more than a mile long and wide enough to accommodate the Sears Tower; they use enough structural steel for thirteen Eiffel Towers; crews have pumped enough concrete to build the Great Pyramids at Giza. But as grandiose as the project is, the central task is simply widening, dredging, and hauling away earth. (The original canal removed enough material to fill a fourteen-foot-wide tunnel through the globe.) Digging through sloppy tropical terrain is still a tough job for machines that aren’t a whole lot different—just bigger—than they were a century ago. Mother Nature still holds the upper hand. Landslides have slowed recent widening and dredging operations, especially on the Pacific side.

The real engineering novelty of the expansion, says de le Guardia, is its use of water-saving basins built alongside the new locks. The canal’s current locks lose about 50 million gallons to the sea each time a boat transits, he notes. With 14,000 vessels moving through each year, that’s a lot of water under the bridge. With the new system, 60 percent of the water used on each transit will be reclaimed, for a 7 percent overall reduction compared to the current system. That water comes from Gatun Lake, the source of drinking water for Panama City as well as the reservoir for the locks. Keeping it potable while maintaining optimum lake levels for shipping is a chief concern for de la Guardia’s team. The canal expansion will raise the level and create wider channels at the Atlantic and Pacific entrances. A redundant system of sixteen rolling gates—eight on each side—is designed to prevent the ultimate nightmare: a ship crashing through the locks and draining Gatun Lake.

Once the job is done, says de la Guardia, “I think it will be time to retire.”