The oil business is booming in the Finger Lakes—without the aid of roughnecks or drilling rigs. It’s culinary oil, and for husband-and-wife entrepreneurs Gregory Woodworth ’94 and Kelly Coughlin ’93, it’s turning into a thriving business, with their products winning over both professional chefs and health- and taste-conscious home cooks.

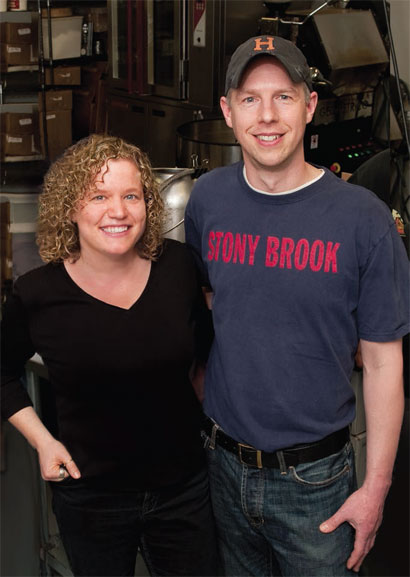

Out of their gourds: Kelly Coughlin ’93 and husband Gregory Woodworth ’94 make oils from squash and pumpkins.

Woodworth and Coughlin’s Stony Brook Wholehearted Foods produces varietal seed oils from locally grown butternut squash, delicata squash, oilseed pumpkin, and kabocha squash—each with its own personality, flavor, and behavior under various cooking conditions. The squash-seed oils have high smoke points, which makes them ideal for frying. The pumpkin-seed oil—derived from an heirloom varietal, the Kikai, grown specifically for its hull-less seeds—doesn’t do well at high temperatures and is best drizzled over salads or soups, or added to rice, couscous, or pasta. Their most popular oil is butternut squash-seed, the product that launched the company. Says Woodworth: “It has a flavor that pleases just about everybody—toasted almonds, walnuts, peanuts, and warm butter.”

The primary markets for the Wholehearted oils are specialty stores such as Dean & DeLuca and Whole Foods. They’ve also been welcomed at natural food stores, including Ithaca’s Greenstar Co-op. A third and fast-growing market is in “tasting stores” in places as far away as New Mexico and Oregon, where sales have more than doubled in the past year. The oils have also found favor with professional chefs in Maine, Massachusetts, and New York City.

Woodworth, who earned an MBA from Bentley College after graduating from the Hotel school, and Coughlin, a CALS alumna who studied marine biology and fine arts, decided in 2005 that they wanted to move their mail-order cookie company from Boston to more easygoing environs. Their dreams of returning to Upstate New York solidified when they learned about Cornell’s New York State Food Venture Center, an incubator for food-related start-ups. A program of the Department of Food Science, the center offers help with product development and safety evaluation, guidance through the regulatory maze, and links to business assistance, financing sources, and local suppliers and service providers. “We get around 1,700 calls a year from people producing, or trying to produce, all kinds of food products,” says technician Herb Cooley. “Some are from companies as large as Unilever and some as small as the Mennonite farmer down the road whose wife is trying to make pickles to sell at the farmers’ market.”

Good seed: The company’s oils make use of a part of the plant that’s usually discarded by the ton.

Cooley told Woodworth and Coughlin about a farm in Brockport, New York, that grows thousands of acres of squash that is peeled, seeded, and cut up for sale at supermarkets. The process leaves behind twenty-five to thirty tons of seeds each year; disposing of them was burdensome—and expensive. Cooley roasted and pressed a test batch. “The roasted seeds were good to eat,” he says, “and when pressed, the oil was plentiful and a beautiful color and flavor.”

He suggested that Woodworth and Coughlin look into extracting oil from the seeds to replace some of the butter in their cookies—and they were impressed. “I thought, This is amazing stuff and with a little tweaking of the flavor profile, I’d like to see this developed into a culinary oil,” Woodworth says. “It became our calling.” After further experimentation and refinement, the couple had a product that seemed more promising than cookies. They switched gears and founded Wholehearted to produce and market squash-seed oil as an alternative to olive oil and other specialty oils, most of which are imported. Drawing on her background in art, Coughlin designed packaging, labels, and a website (wholeheartedfoods.com). She aimed for clarity and simplicity. “You don’t need a lot of bells and whistles to showcase a product you’ve put so much of yourself into,” says Coughlin. “We care about how we make that product, and that’s what we want to get across.”

Venture capitalists found the idea too risky, so the entrepreneurs moved ahead on a shoestring budget, with equipment borrowed from Cornell. They got a boost when Noah Sheets, the chef at the New York State Governor’s Mansion, purchased their squash-seed oil for a special event—becoming their first official customer. Sales took off; last year they were up 25 percent and they continue to rise. The company’s modest profits have fueled growth, with new equipment including an expeller press from Germany and a roaster custom manufactured by one of the few U.S. producers. “And maybe one day,” muses Woodworth, “we’ll have the time to go back to doing cookies.”