Negen Farad ’98.All photos provided

Comedian Negin Farsad ’98 often begins her standup sets by walking onstage, grabbing the microphone, and taking the pulse of what is generally a predominantly white crowd. “Just by round of applause,” she asks, her voice rising enthusiastically with each word, “who in the audience is an Iranian-American Muslim female? Woo-hoo!” Farsad is an anomaly on several counts—a female in a male-dominated profession, a Muslim in a post-9/11 world, and a comedian with ultimately serious intentions. So she doesn’t only observe and question and quip; she also enlightens her audiences about an ethnicity and a religion that are perceived by many as mysterious, and are often misunderstood.

Throughout the spring and fall of 2011, Farsad took her show on the road, far from her usual comfort zone of liberal-minded Manhattan comedy clubs. She performed in Gainesville, Florida, where a pastor made headlines by burning the Qur’an; in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, where the opening of a new mosque was met with protests, lawsuits, and arson; in Tucson, Arizona, home to virulent antiimmigration legislation.

The venues were carefully chosen as part of a tour in which a group of Muslim-American comedians aimed to use humor to humanize Islam, to shift the stereotype from Jihadist to jokester. They traveled to places like Birmingham, Idaho Falls, and Salt Lake City—”places that, needless to say, love the Muzzies,” says Farsad, who, along with Palestinian-American comedian Dean Obeidallah, co-directed the filming of the tour. They collected nearly 300 hours of footage, including interviews with everyone from gun shop owners and small-town imams to Jon Stewart and Rachel Maddow, and distilled it into a feature-length documentary. The Muslims Are Coming! premiered to sold-out crowds in October at the Austin Film Festival, winning the Comedy Vanguard Audience Award and bolstering Farsad’s impressively hyphenated resume. Along with being an Iranian-American writer-performer-producer-director, she is very much a comic-activist.

After a spike in anti-Muslim sentiment following the September 11 attacks, Farsad sensed that the hostility leveled off for a while, but she says it has risen again in the past few years. She sees it in the “birther” conspiracy claiming that President Obama is a foreign-born Muslim, an accusation she considers both uninformed and inherently anti-Islamic. She saw it when home supplies chain Lowe’s pulled its advertising from cable television’s “All-American Muslim” after the hitherto unknown Florida Family Association derided the show as “propaganda that riskily hides the Islamic agenda’s clear and present danger to American liberties and traditional values.” And she saw it in the darkly comic, truth-is-stranger-than-fiction incident last May, when four Muslim clerics were barred from their flights and thus arrived late to a conference . . . on Islamophobia.

So, armed with some courage and comedy chops, Farsad and friends attempted to introduce themselves to red-state America. Besides offering free standup comedy, they fielded questions after each show, turning it into a town hall meeting of sorts. Between shows they set up sidewalk booths, inviting residents to ask them anything they wanted. They played “Name That Religion,” reading scripture and asking if it came from the Old Testament, the New Testament, or the Qur’an (contestants repeatedly attributed some of the harshest passages to the latter—and were usually wrong). They even held up signs that said “Hug a Muslim.”

The comedians were a purposely diverse bunch, an attempt to reflect the variety in the Muslim diaspora. Obeidallah is half Sicilian. Kareem Omary is half Peruvian. Maysoon Zayid has cerebral palsy. Preacher Moss is black. As Farsad puts it, she wanted to convey that some Muslims are devout and others are “I’m Muslim, but pass me that ham sandwich.” Toward that end, she occasionally adopts a faux-naïve persona on stage. She’ll bring up the Arab Spring revolutions, for instance, and say, “I didn’t realize there were so many countries in the Middle East. I thought it was one big brown-violet blob. Next thing you know, they’re going to tell me there are different cultures and languages . . . Shut up! That’s crazy!”

On how Twitter and Facebook were credited with fueling the Arab Spring: “Where was Apple? Apple should have been out there like, ‘Are you trying to stage an opposition protest? There’s an app for that: i-skirmish.'”“The Muslims Are Coming!” was touted as a “laughing and listening” tour, but Farsad was somewhat surprised at many residents’ willingness to actually listen. And she listened to them, a reminder that nothing breaks down stereotypes—on both sides of the equation—like exposure to real people.

There’s a moment in The Muslims Are Coming! when a man in Georgia suggests that Farsad should stop referring to herself as Iranian-American. “My ancestors are from Holland, but I don’t claim to be Dutch-American,” he tells her. “If you want to be mainstream, then you’re no longer an Iranian Muslim. You’re American.” Smiling through gritted teeth, Farsad agreed to disagree. Months later, back home in Manhattan and her sixth-floor production offices overlooking Spring Street in SoHo, she explains, “I don’t think they realize that every time I pick up the phone and talk to my parents, it’s in a completely different language.”

Farsad’s family—father Reza, mother Golnaz, and older brother Ramin—emigrated from Iran in 1972 when Reza was accepted into a medical residency program at Yale (he is now a cardiovascular and thoracic surgeon). Eight years later, when their only daughter was two, the Farsads moved to Virginia; they were one of two Persian families in Roanoke at the height of the Iran hostage crisis. When Negin was seven, they moved to Palm Springs. At home, the family conversed in Farsi and Azeri, a regional Turkic language. Although it wasn’t a strict Muslim household, there were cultural restrictions—no boyfriends allowed, for instance, and no leg-shaving, the latter being problematic for a dark-haired adolescent in sunny California.

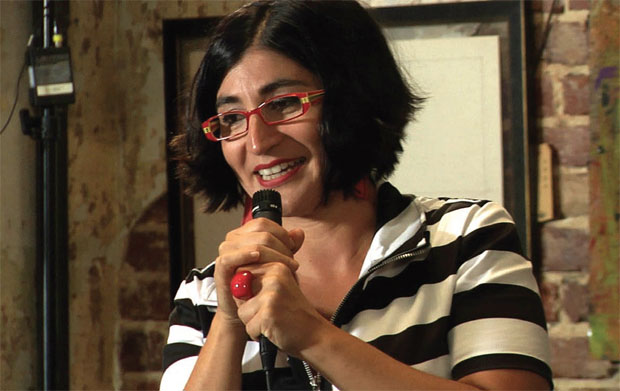

Farsad on stage

It was less of an issue 2,500 miles away in Ithaca, not only because of the weather but because Farsad and her parents adopted what she describes as an ongoing “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. At Cornell, her double major reflected an inner dilemma. On the one hand, she majored in government, the long-term plan being to return to Palm Springs, earn some political cachet, run for Congress, become the first female Muslim president, and end the nation’s religious divide. But she also majored in theatre arts, the short-term plan being to enjoy herself.

In high school, she had acted in a production of Neil Simon’s play God’s Favorite. Farsad, a diminutive Persian girl with a high-pitched voice and a low tolerance for religious dogma, played God. The following year, after being mesmerized by a Skits-o-Phrenics performance during Cornell’s new student orientation, she auditioned and earned a spot in the sketch comedy troop. It was, she says, “twelve white dudes and me,” which was solid preparation for the world of professional comedy.

Nearly as unusual as being a female Muslim comedian is the fact that she is atypically Type A. “I’m pretty boring that way,” she says. “I don’t really drink, just socially. I don’t do drugs. I don’t smoke. I wake up early. It’s like I want to get a good grade.” Whereas many standup comics riff and improvise, guided by only a few bullet points as an outline, Farsad is meticulous. She types up punch lines word for word, tests the material two or three times a week, records each set, examines why and where the big laughs came, removes the weak moments, then puts it out there again to see if it still works. A first-draft four-minute bit becomes a polished sixty seconds.

On alcohol being banned in an Islamic republic: “Iran feels a lot like Prohibition-era United States. It’s literally the roaring thirteen-twenties over there.”For a while, Farsad crafted a non-comedy career just as meticulously. She earned two master’s degrees from Columbia (in race relations and urban planning) and landed a job as a policy adviser for the City of New York. For a year and a half she led a double life, spending her nights performing at comedy clubs. “I was always champing at the bit to leave the office and go do a show,” she says. In 2006, she quit her day job. Instead of changing the world through government work, she would do it one laugh at a time.

Like most comics, Farsad mainly draws on personal experiences—dating strategies, family quirks, mom issues. But in her case, those experiences tend to suggest a more profound level of discourse. Jeff Foxworthy can do a gag about a redneck family reunion, and Billy Crystal has offered countless bar mitzvah jokes. But when Farsad embarks on a comedy bit about attending a family wedding— in an Islamic republic—it has more bite. “If you’re doing a joke about your mom in Wisconsin, it doesn’t seem political,” she explains. “But if you’re doing a joke about your aunt in Iran, that becomes a political joke.”

Which is fine, because Farsad is a political junkie. Sure, she may toss in the occasional Justin Bieber quip, but she says it makes her feel bad about herself, “like I’m not doing anything to promote good in the world.” She is only half kidding. In fact, she spends much of her time marrying her two loves: public policy and theater. She calls it “satirical social justice.” After launching a production company, Vaguely Qualified Productions, Farsad wrote, directed, and produced her first feature film, Nerdcore Rising, a comedy about a subgenre of hip hop music performed by and for selfproclaimed nerds. She has since produced a variety of satirical Web videos and public service announcements for organizations such as the AFL-CIO and MoveOn.org. Her subject matter has ranged from health care to Citizens United to tax shelters in the Cayman Islands.

Farsad was also asked, as part of a series commissioned by Queen Rania of Jordan, to produce a short video about Arab stereotypes. She created a montage of various people discussing the most offensive or absurd comments directed at them (“You’re Arab? That’s great. I love hummus!”).

“Something satirical is going to be way more memorable and turn more heads than just a dry lecture,” says Farsad, as she prepares to run off to vocal lessons in preparation for a two-person musical she co-wrote called “The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict.” In the show, a man named Jewlandia (“It’s a working title,” he explains) and she (“Palestine”) are accidentally assigned to the same convention booth in Geneva in 1948.

“I don’t know why we can’t share until they sort this whole thing out,” says Jewlandia.

“Um, okay,” says Palestine. “I can’t imagine it will take them that long.”

After a botched one-night stand, Israel doesn’t call, Palestine gets angry, and conflict ensues. But, as Farsad explains on her website, “somewhere in the middle of all the chaos, in the middle of all the wars, and the embarrassing run-ins, rebound relationships, and pint-after-pint of ice cream therapy, Palestine and Israel may have found LOVE.”

On dressing the part: “It isn’t decreed in the Qur’an that you have to be covered up; it is whatever your personal notion of modesty is. Mine involves cleavage.”Farsad’s brand of comedy has earned her accolades aplenty. The Chicago Tribune hailed her “sharp, Janeane Garofalo wit.” A New York theater reviewer wrote that she “recalls a Tracy Ullman of Middle Eastern descent.” The Huffington Post named her one of its “fifty-three favorite female comedians.” The reviews from her parents are more complicated. “This is a completely different line of work than anything they’ve understood, and it’s not one of those I’m-proud-of-you households. I don’t even know how they would say that in Farsi. But I think they are,” she says, and then she pauses for a moment. “I know they are.”

On one of her first callbacks after embarking on the auditioning process as a comedic actor in New York, a casting director told Farsad, “You’re so great. But you’re too ethnic for the part. And if we went that route, you’re not ethnic enough.” He was essentially talking about the color of her skin— too dark on the one hand, not dark enough on the other. Add religion on top of race, and the obstacles grow even more imposing. In his book Islamophobia/Islamophilia: Beyond the Politics of Enemy and Friend, John Jay College sociologist Mucahit Bilici writes: “The discrimination, prejudices, and stereotypes from which other Muslims suffer are a godsend for the Muslim comedian.” However, there is another side to that coin—when the performers themselves encounter those prejudices. In The Muslims Are Coming!, comedian Colin Quinn marvels at the notion of a female Muslim standing alone on stage and delivering occasionally racy material. “I can’t imagine,” he says, “the amount of stepping between raindrops that must entail.”

In her standup, Farsad constantly walks a fine line— poking fun at the Muslim world while putting a friendly face on it, balancing the personal and the political, and constantly risking rejection both from those prejudiced against the Islamic faith and those who practice it. During the “Muslims Are Coming!” tour, one observer commented on an Internet forum, “I wish these folks the best. They may well be setting themselves up to be killed.” It turned out that the anti-Islamic response was subtler, at least sometimes. There were occasional driveby racist epithets and anonymous venom (a YouTube watcher responded to the movie trailer by asking, “Didn’t these guys play at the World Trade Center?”) Most frequent, however, was the query: Why don’t American Muslims do more to denounce terrorism? “You can redo that question in various different scenarios for different ethnic groups and different subcultures, and it’s always a dumb question,” says Farsad (and in fact, several interviewees in the movie point out that Catholics aren’t constantly asked to denounce pedophilia). “But I replied, ‘They do. But these people who committed these crimes aren’t real Muslims. They’re the nutsos.'”

However, on occasion Farsad has also gotten negative responses from offended Muslims. Sometimes it comes in the form of hate mail, sometimes simply as silence. The first time she encountered such disdain was when she was invited to do a show at Northwestern University in her early standup days. The Iranian Student Association had invited members of the local Iranian community to attend. “I had no idea that Persians would even think my comedy was anything edgy or risqué,” she said, “until I started talking about sex and my dating life, and I heard crickets in that room.”

If comedy were classified the way Islam categorizes food and sex—as either halal (permitted) or haram (forbidden)— Farsad’s jokes would mostly fall on the haram side of things. In many Muslim cultures, the mere mention of sex is taboo. Yet Farsad isn’t averse to starting a comedy bit by saying, “I recently had to get an STD test because I was a raging slut for a period of my life . . . that ended last week.” She mainly does it because it’s funny—particularly when she then delves into her mother’s reaction or offers an impression of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad doing a public service campaign for safe sex. (“Practice safe intergender flesh relations . . . and destroy Israel.”) But she also aims to convey that, as in all religions, Muslims have varying levels of secularism, observance, and tolerance. And, she admits, she likes to be provocative, to shock the audience a bit. Still, when a group of Hijab-wearing women walked out en masse during her set in Tucson last October, it stung. “Did it hurt my feelings? Absolutely,” she says. “It feels awful.”

Farsad insists that such reactions just strengthen her resolve. So she continues her balancing act—dispelling stereotypes while confronting patriarchy, educating about Muslim diversity while taking on Islamophobia, plying her trade in an industry where cynicism has become a staple while believing that she can be an agent of change. She’s willing to do it one person at a time; she sees each viewing of The Muslims Are Coming! as a chance to reach hearts and minds. “This sounds kind of dorky,” she says, “but I feel like if people have never had a Muslim friend, I’d like for this movie to be their first.”

Brad Herzog ’90 is a CAM contributing editor.