On Memorial Day weekend, Cornell will celebrate its 150th Commencement—welcoming visitors from around the world to honor the achievements of its newly minted alumni. Drawing a crowd of more than 30,000 to the Hill, Commencement is by far the University’s biggest annual event—and year after year, it goes off more or less without a hitch, thanks to the efforts of a cadre of dedicated staff and several hundred volunteers. As one of those staffers, facilities event coordinator Julie Parsons ’06, puts it: “It’s the premiere event of the year. It’s the grand poobah. It’s the apex.” Graduation, Parsons adds, “is something that these kids have worked at least four years for. It’s a really big deal.”

Graduates entering Schoellkopf Field for Commencement 2015Lindsay France/UREL

To mark Commencement’s own sesquicentennial, CAM decided to take a comprehensive look at the University’s annual celebratory blow-out—the behind-the-scenes logistics, the various traditions, the vicissitudes of weather, and more. Like much about Cornell, over the past century and a half it has both evolved and stayed fundamentally the same. “Big transitions are important,” President Martha Pollack observed at Commencement 2017, her first. “It’s why we mark them with celebrations, like the one we’re participating in now. They’re times for reflection—for looking backwards at what you’ve experienced and what you’ve learned, and looking forward, toward what you’ll do next, to your next adventure.”

History Lessons

Cornell held its first Commencement in 1869, the year after the University opened; the inaugural class comprised eight students who’d transferred from other institutions. The ceremony was held at the downtown Ithaca library that Ezra Cornell had funded. As is noted in the program for the current ceremony, each graduate “mounted the stage to receive a vellum diploma rolled and tied with a carnelian silk ribbon. President [Andrew Dickson] White had composed the wording of the diplomas. Ezra Cornell himself had mailed the invitations. The ceremonies ended with the awarding of prizes and an address by President White. At the president’s reception later that evening, strawberries, ice cream, cake, and lemonade were served.” In those early days, says Cornell history expert Corey Earle ’07, “these were three-hour affairs, with the graduating seniors reading their scholarship.”

In 1883, the ceremony moved from the library to the campus armory, a more spacious venue located on what’s now the Engineering Quad. It was first conducted outdoors—using Libe Slope as a natural amphitheater—in 1912. Over the decades starting in the Twenties, Commencement was variously held in Bailey Hall, Barton Hall, and Schoellkopf Field, before permanently taking up residence in Schoellkopf in 1975.

Historical Venues

The first class to celebrate Commencement after spending four years on the Hill graduated in 1872—and when members of the previous classes came back to mark the occasion, they essentially founded Reunion (and the Alumni Association). In 1877, trustees designated an official Alumni Day, to be held the Wednesday prior to graduation. “Alumni would come in before Commencement and stick around for the party,” says Earle. “That lasted until they realized there wasn’t enough room on campus for everyone, with parents coming in.”

In 2003, the University began honoring December graduates with their own ceremony, held in Barton (though those alums are also welcome to march the following May). It’s a more intimate affair, with degrees conferred individually. The event has been growing in popularity: last year’s ceremony, with about 480 graduates and their families, drew the biggest crowd ever. Logistics for winter Commencement were modeled on May’s PhD hooding ceremony, which marked its twenty-fifth year in 2017. Held in Barton on Saturday evening, the event was spearheaded by then-President Frank Rhodes as a way to confer special honors on Cornell’s highest degree recipients.

Prep Work

As director of Cornell’s Commencement office, Connie Mabry has been the event’s field marshal since 1989. And as she points out, planning for it begins as early as during the previous one, as staffers are taking notes throughout the weekend to help them improve things the following year. “We’re always working on Commencement,” says Mabry. “It’s really a year-long process and then some. I’m always thinking ahead. Thankfully, it doesn’t change too much, and I keep putting that out there: if it’s not broken, let’s not try and fix it.”

It Takes a Village

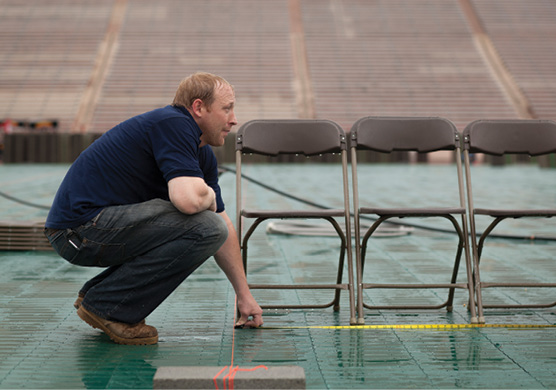

Pulling it off requires enough logistics to fill an inch-thick facilities plan that Mabry maintains. (Its cover sports a quote from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: “It has long been an axiom of mine that the little things are infinitely the most important.”) The document contains details on everything from the number and placement of chairs at various events throughout the weekend to a map showing how to set up the ushers’ locker room in Schoellkopf. According to Parsons, facilities staff put in more than 3,000 hours just for the two major events—Commencement and Convocation—for which Cornell rents a whopping 7,500 chairs. One of the most onerous tasks is installing the green plastic flooring that protects Schoellkopf’s artificial turf, which takes eight staffers as long as four days to roll out. Just putting up signs to guide visitors is a major undertaking: in a matter of days, staff install about 1,000 of them on campus and around Ithaca. (They just as swiftly take them down, lest they vanish—then turn around and put up another set for Reunion, which begins less than two weeks later.)

“It’s chaos—long hours and chaos,” Parsons says of the weekend overall. “A large group of us are here early mornings to late evenings, making sure that everything has been checked off the list. Did we put the banner up for the next morning’s event? Did we put up those barricades or cones where they need to be? It’s making sure that all of those finer details get done, walking around during Convocation and Commencement with a headset and listening to all of the concerns that folks have about the plumbing or something that needs to be cleaned up in a certain restroom.”

Commencement weekend comprises more than 100 events all around campus—from the major ceremonies viewed by thousands to gatherings in the individual schools, colleges, and departments. There’s a commissioning ceremony for ROTC graduates; a concert by the Glee Club & Chorus; a hooding ceremony for new veterinarians. After Convocation in Schoellkopf on Saturday, the president hosts a reception on the Arts Quad for all grads and their families; in a nod to the fare at Cornell’s first-ever Commencement, Dairy Bar ice cream is served. (This year, according to Cornell Catering director Brandon Fortenberry, more than 600 gallons are scheduled to be scooped.)

While staffers and volunteers fan out all over the Hill, the weekend’s nerve center is a command post on the hinterlands of campus, across Dryden Road from the Botanic Gardens. There, about a dozen staffers drawn from Cornell Police, transportation services, the Commencement office, the Environment, Health & Safety department, and more are on duty to cope with any issues or emergencies that crop up. (A similar crew gathers there on Slope Day.) “We take lots of precautions and have evacuation plans in place,” Mabry says. “Thankfully, nothing has ever happened.”

As Parsons notes, facilities staff take particular pride in making the campus look its best for Commencement, when legions of friends and family—who may be getting their first extended look at Cornell—descend on the Hill. Staffers do everything from trimming ivy to filling potholes to making sure that stairways are clean and well-lit. Along the procession route, they repair cracks in the sidewalk and cover drains to eliminate trip hazards. “We pay special attention to all those fine details for all of the buildings and events,” she says, “because we want the graduates and their families to have an awesome time.”

One thing that doesn’t happen during Commencement weekend? The physical distribution of diplomas. Because of the logistical hassle of handing them out—and because some graduation requirements, like final grades or a completed swim test, may still be lingering—new alumni now receive their sheepskins in the mail. “They used to be distributed by the colleges, but three or four years ago that changed,” says Mabry, “and it has made everyone’s lives so much easier.”

Dressing for the Occasion

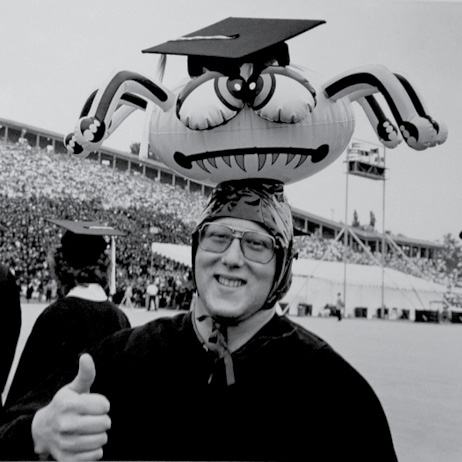

Like so much of modern life, today’s graduation garb is procured online: students place their orders with Cornell’s vendor and can pick up their caps and gowns over the course of several days. About 500 boxes’ worth are distributed in the Teagle Hall multipurpose room. The gowns, which are rented, must be returned by 5 p.m. on Sunday; the tassels have always been keepsakes. “Last year was the first year that the cap was a ‘keeper cap’ rather than a rental,” Mabry says, “because students are doing more and more decorating.”

Creative Mortarboards

Long Walk

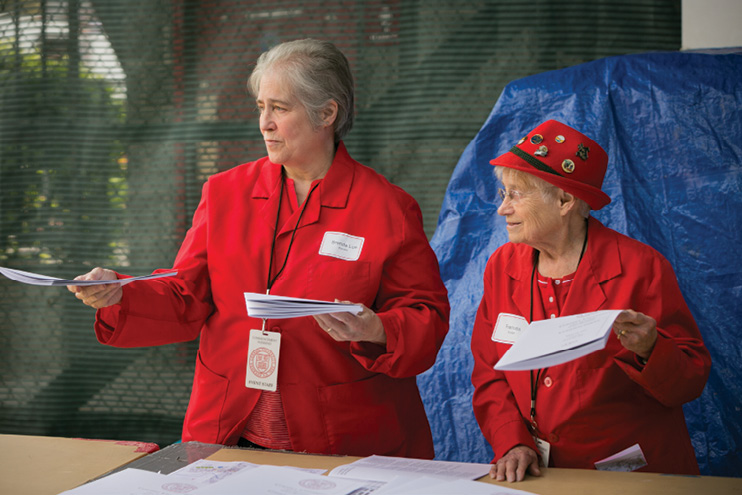

Earle is not only a font of lore about Commencements past; he has also volunteered at the event for a decade, serving as head usher on the Arts Quad since 2010. In that role, he’s in charge of about sixty red-blazer-clad volunteers who get graduates lined up by college, four abreast, as they prepare to march. The berobed procession also includes faculty, administrators, trustees, and—accompanying the president at the rear of the group—the University mace bearer. “Quarter of ten is when the chimes play and the procession starts moving,” Earle says. “The goal is to get the president into the stadium at exactly eleven o’clock. The amazing thing is every year I’ve done it—and I don’t know how it happens—it’s been within a minute or two that the president walks in.”

Processions

Another of the Arts Quad ushers’ duties is to distribute the ceremonial banners bearing the names and symbols of the individual schools and colleges; the grads who carry them are chosen by the academic administration, honored for extraordinary performance such as a high GPA or prominent leadership role. (Serving as a degree marshal—the students adjacent to the banner bearers who carry small wooden batons—is a similar laurel.) In addition to signaling to the announcer that the various schools and colleges are entering the stadium, Earle says, the banners are “a nice element that helps break up the procession and adds some color.”

Once the procession arrives on Schoellkopf Field, another group of ushers springs into action. Their job: to get the grads into their seats with both speed and clockwork precision. “There’s a systematic plan that’s been mathematically calculated as to how the students come in and where they will be seated when,” Mabry explains. “It’s like a big train station; they can’t come in and stand in the aisle and wait until everybody gets seated. We use several aisles to get them in and seated within an hour.”

More Shine than Rain

There has long been talk of a Commencement weather god who protects the Hill from storms, even when it’s pouring in the next town over. And indeed, since the ceremony took up residence in Schoellkopf in 1975, it has never been moved indoors because of inclement weather. But though grads and their families have enjoyed some postcard-perfect days, there have also been some wild extremes. In 2016, Mabry says, it was in the nineties during Convocation on Saturday—and on steamy Schoellkopf Field on Sunday, the mercury topped 100, prompting the University to distribute tens of thousands of bottles of water to the sweltering crowds. Three years earlier, by contrast, temperatures had been in the fifties. “Everyone was bundled up,” she recalls. “The campus store sold out of whatever supply they had left from winter—coats, hats, mittens, blankets, socks. They kept bringing stuff in from their warehouse.”

Weather Both Foul and Fair

Commencement 2016 was also the site of a now-legendary downpour that took organizers unawares, unleashing nearly a quarter of an inch of water in about half an hour. “We had two blast rainstorms during the procession that we didn’t know about until they were coming over the Hill,” Mabry says. “Even Binghamton meteorology didn’t know they were going to hit us. We had like a two-minute warning.” Berobed dignitaries found themselves leaping over puddles on the path from the Arts Quad to the ceremony. “Everybody just kept on walking, and everybody got soaked,” she recalls. “It was really hot, so people didn’t mind.” But since lightning threatened—posing safety concerns—the ceremony was truncated, with a quick address and all degrees conferred simultaneously rather than by school and college. The whole ceremony was dispatched in half an hour, likely making it the shortest Commencement in University history.

And if Cornell’s weather luck truly runs out, and the ceremony has to be moved into Barton? Only the graduates themselves will be able to attend, with no room for families or even faculty. “It will be the same ceremony as it is in the stadium,” says Mabry. “All the colleges will be recognized en masse. They’ll stand up and sit down as a group. Everything would be the same inside as it would be outside.” She adds: “We hope it never happens.”

Life Lessons

While most colleges and universities jockey to land a prestigious big-name speaker for graduation, Cornell has long gone a different route: the Commencement address is almost always given by the University’s president. There have been a few exceptions for illness or logistics (for example, in 2016 Acting President Hunter Rawlings had a prior commitment that weekend, so Provost Michael Kotlikoff stood in for him). There have also been a couple of exceptions to mark major moments in history. At Cornell’s 100th Commencement in 1968, President James Perkins invited former U.S. secretary of health, education, and welfare John Gardner to address the crowd; his speech, entitled “Uncritical Lovers, Unloving Critics,” traced a 600-year tour of history—stretching three centuries into the future. “The twenty-third-century scholars understood that where human institutions were concerned, love without criticism brings stagnation, and criticism without love brings destruction,” he said. “And they emphasized that the swifter the pace of change, the more lovingly men had to care for and criticize their institutions to keep them intact through the turbulent passages.”

The following decade, to mark the U.S. Bicentennial in 1976, President Dale Corson invited eminent history professor Walter LaFeber to give the Commencement speech. “I felt that something significant should be said by someone who could say it with authority,” Corson later explained. As LaFeber told the crowd: “The founders of this nation and the founders of Cornell shared a common commitment, indeed a common passion: a belief in the power of ideas to transform individual lives and improve human society.”

With the president giving the Commencement address, Cornell’s big-name “get” comes the day before, at Convocation. Speakers for the event, which began in 1985, are chosen by a senior class committee. Held in Barton Hall for most of its first two decades, Convocation often featured alumni speakers in its early years, including psychologist Dr. Joyce Brothers ’47, astronaut Mae Jemison, MD ’81, former attorney general Janet Reno ’60, and broadcaster Keith Olbermann ’79. More recently, the University has lured major non-Cornellian speakers including (in 2004) former President Bill Clinton—prompting the event to be relocated to Schoellkopf to handle the anticipated crowds. (Except for 2005, it has been held there ever since.) Other prominent speakers have included poet Maya Angelou, former New York City mayors Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg, and movie star James Franco.

Speakers

In a meta moment, actor Ed Helms—who portrayed a rabidly loyal Cornellian on the hit sitcom “The Office”—delivered the address in 2014. “You do realize I’m not actually Andy Bernard, right?” he asked the crowd. “He isn’t a real person. He is a character from a TV show, and I am the actor who played him. Or did you actually invite a fictional person to give this speech?” Last year, former Vice President Joe Biden—who was fêted with a custom ice cream flavor from the Dairy Bar—delivered a rousing speech whose topics ranged from Vietnam-era activism to the perils of social media echo chambers. “I’m so tired of both political parties,” he confessed. “I’m so tired of the incrementalism. I’m so tired of thinking small. When has America ever thought small? We never have. It’s time for America to get up. It’s time to regain our sense of unity and purpose and remember who we are. With all the brainpower and energy I see in front of me, I know that nothing and no one in this world can beat us.”

Degrees of Separation

Another Cornell tradition is a refusal to grant honorary degrees. As Earle notes, A.D. White was an early opponent: “He said, ‘You earn Cornell degrees. Honorary degrees have become useless and are cheapening college education.’ ” In University history, Earle points out, “we’ve only given two—and it was pretty controversial.” In the late 1880s, Cornell’s second president, Charles Kendall Adams, convinced trustees to award honorary JDs to David Starr Jordan (Class of 1872), the first president of Stanford, as well as to White himself. “I think White took the degree because he thought it would be rude to refuse, and he was very careful about diplomacy and decorum,” says Earle. “He had honorary degrees from other places, but he didn’t want them to be part of the Cornell tradition.” As Earle notes, Adams’s gesture didn’t bode well for his future at the University, and the ensuing uproar was one reason he was forced to resign in 1892. “Hundreds of alumni signed a petition saying, ‘This is ridiculous—we don’t give honorary degrees,’ ” says Earle. “That was just one of many examples of Adams not being in tune with the faculty, alumni, and trustees.”

The mace being carried in the Seventies.Russ Hamilton/RMC

A Blow for Knowledge

The University mace is a ceremonial object that symbolically references the ancient weapon after which it’s modeled. Commissioned by President Deane Malott and designed in the early Sixties by a member of the Goldsmiths’ Guild of London, the mace (according to a description on the University website) “consists of a tapered silver shaft surmounted by a golden terrestrial globe. The silver ribs surrounding the globe symbolize the universality of Cornell’s interests and the worldwide affiliations of its faculty, students, staff, and alumni. At the top of the shaft, the Cornell Bear holds an oar.” That oar got slightly bent in 1970, when Professor Morris Bishop 1914, PhD ’26—then in his late seventies—wielded the mace as a weapon. In what Earle calls “the only time the mace has been used for its actual purpose,” Bishop employed the yard-long, fifteen-pound object to successfully fend off a pair of radical protesters who tried to seize the microphone at Commencement. As President Dale Corson reminisced in the Daily Sun when Bishop passed away in 1973: “The jab was given in typical Bishop style, with spontaneity, grace, and effectiveness.”

Out of Towners

As the legend goes, you should book your Commencement weekend reservation at the Statler as soon as your child gets into Cornell. But in fact: you shouldn’t, and you can’t—because the hotel is already filled with trustees and other dignitaries. As Peggy Coleman of the Ithaca/Tompkins County Convention & Visitors Bureau notes, Commencement is the single biggest annual driver of visitors to the area’s hotels and restaurants—and in the past, grads’ families may have had to stay as far afield as Auburn, Elmira, Cortland, and Watkins Glen. But with the recent construction of several new hotels in Ithaca and the advent of Airbnb, the situation has shifted: Coleman reports that 2017 “was the first known year that all of the lodging properties didn’t sell out for Cornell University Commencement, and the typical overflow of guest rooms to neighboring communities did not occur.”

That trend has been reflected in the decline in demand for on-campus lodging, an affordable option in which each graduate can book up to eight single beds in residence halls. (The three-night package, which includes buffet breakfast, parking, and campus shuttles, costs around $200 per person.) While in the past about 4,000 guests would stay in the dorms, Mabry says, by 2015 the number had dropped to 2,300—and last year, it was down to 1,700.

When it comes to restaurants, Coleman says, “it is the wise senior who finds his or her graduation celebration location months in advance, especially for larger parties.” She points out that for Ithaca’s hospitality industry, Commencement has the benefit of offering guaranteed business, year after year. “Guests are coming to see their loved one graduate and are not likely to cancel their visit,” she says. “There isn’t the potential to lose the business to an alternate destination, as long as Ithaca is home to Cornell University.”

Minor Mishaps

Given the scale of Commencement, the number of things that have gone wrong over the years is surprisingly low—a tribute to the staff’s meticulous behind-the-scenes organization. Some problems have been solved by planning and rule enforcement: for example, a ban on bringing Champagne bottles into Schoellkopf has eliminated the occasional injuries from careening corks. Inevitably, there have been some youthful hijinks, including some recent grads who inexplicably carted a toilet all the way from the Arts Quad and into the stadium. A couple of years ago, one incurable romantic caused a minor hubbub when he proposed to his girlfriend on the field in the middle of the ceremony. (Says Mabry: “I think she said yes.”)

Then there have been the dramas that visitors and grads never saw—like when a golf cart got its pedal stuck, started spinning wildly in a circle, and took out a whole section of chairs that facilities workers had just set up in Schoellkopf. Or when a staffer was running to retrieve a ceremonial donation check from backstage during President Bill Clinton’s Convocation speech and nearly got tackled by the Secret Service. Or when workers suddenly heard a massive BOOM while getting the stadium ready one Thursday before Commencement. “It was like a cannon had gone off,” Mabry says. “The guys hit the deck. But when they looked around, everybody was fine.” The culprit: a rented forklift’s huge tire, which had blown. “Sunday afternoon of the same week, KABAM again,” Mabry recalls. “It was another tire. Two in four days!”

Making Happy Memories

I don’t even remember who spoke at my graduation I was so tired hanging out with all my friends one last time at my place that I passed out for most of it and my wife had President Clinton speak at hers. Not fair.

1987. President Rhodes reciting the Gaelic blessing “May the road rise up to meet you…” as only he can. One of my most special memories.

In 1974 were were the last class to use Barton Hall- it was real “cosey”.

Class of 1976 and I remember Prof Walter LaFeber’s speech. It was momentous that our graduation year coincided with the bicentennial. Weather was beautiful, sunny, and hot!

Also Class of ’76 and recall the Bicentennial fever, Prof. LaFeber’s powerful message and the heat way up high in the stadium!

1969. Barton Hall. A friend and I carried balloons in the procession into the hall. Our parents, somewhat abashedly, were able to pick us out from the gathered throng on the floor of the hall.

My understanding is that David Burick, my freshman writing instructor, was the one Morris Bishop hit with the mace. The mace suffered some slight damage but wasn’t repaired — the damage was part of the history.

We had a beautiful day when we graduated in May 1982.