Harry Edwards still turns heads. When you’re NBA-tall, cultivating a jutting white beard against dark skin, and clad in black from head to toe, you tend to attract attention. So eyes follow him as he squeezes his six-foot-eight frame alongside a tiny table at Panera Bread in his hometown of Fremont, California.

Edwards, PhD ’73, is no longer the beads-and-beret-wearing militant once described as “Nat Turner, Malcolm X, and Paul Robeson all rolled into one,” a mountain of a man who made international headlines forty years ago when he was briefly a member of the Black Panther party and his movements and statements were monitored by J. Edgar Hoover himself. Indeed, these days he is part of the mainstream—a retired professor often sought by the media for commentary and analysis. But even at sixty-five, he remains imposing. And the way he tells it, he remains the same Harry Edwards.

It is the cusp of spring, and the upcoming Summer Olympics are awash in controversy. Newspapers have been brimming with stories of activists using the Games in Beijing as a backdrop for expressing human rights concerns. After three representatives of Reporters Without Borders were arrested during the Olympic flame-lighting ceremony in Athens when they unfurled a banner showing the Olympic rings as handcuffs, the torch relay itself—the so-called “Journey of Harmony”—has become a magnet for demonstrators decrying China’s use of force against Tibetan protesters. Darfur activists are calling the Games “the genocide Olympics” and calling on athletes to boycott them in an attempt to shame China, Sudan’s largest oil consumer, into helping stop the killing there. Meanwhile, fifteen members of the U.S. House of Representatives have sent a letter to President Bush urging him not to attend the Olympics. In response, the Global Times newspaper, affiliated with the Communist Party mouthpiece People’s Daily, has stated that “the West wants to bind sports and politics.” For Edwards, the echoes of 1968 are growing louder.

According to the Olympic charter, “no kind of demonstration or political, religious, or racial propaganda is permitted at Olympic sites.” However, that hasn’t necessarily meant a separation between politics and the Games. In 1936, several groups called for boycotts of the Berlin Games after Adolph Hitler rose to power, and an alternative People’s Olympics was staged in Spain. Twenty years later, even Switzerland was part of a boycott of the 1956 Melbourne Games to protest the Soviet Union’s invasion of Hungary.

But Edwards’s attempt in 1968 to engineer an Olympic boycott by African American athletes was different. It was a rift from within, a proposal that a super-power be shamed by its own athletes. While black athletes had been winning medals over the previous thirty-six years, “they were being hailed before the world as symbols of American equality—an equality that has never existed,” Edwards said at the time. So here was all the strife of that defining year—the Tet Offensive, the Prague Spring, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the urban riots, and the rise of a new black militancy—brought to the world of balance beams and basketballs.

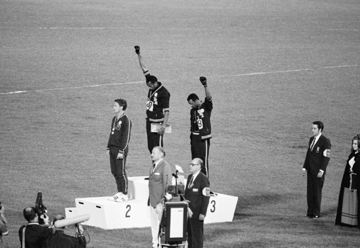

In the end, the many months of agitation and vilification were distilled into a single enduring image. Edwards, then a sociology instructor at San Jose State, watched on television as two of his students dominated the 200-meter dash at the Summer Games in Mexico City. Tommie Smith won, setting a new world record; John Carlos finished third. Just before the medal ceremony, Smith pulled a pair of black gloves from his bag and handed the left one to Carlos. Each wore long black socks and no shoes. Smith later explained that this represented black poverty in America. Smith tied a black scarf around his neck— representing black pride. During the playing of the U.S. national anthem, both raised their black-gloved fists straight above their bowed heads—a symbol of black power. “The totality of our effort,” said Smith, “was the regaining of black dignity.” It remains one of the most poignant moments in sports history. “I was elated. I understood what it meant,” says Edwards in a confident baritone that is part professor, part preacher. “If these athletes, who have made it to the apex of their sport, stand on a podium and say there are things in sport and in America that are terribly wrong, everybody has to pay attention, whether they agree with them or not.”

To understand how Edwards became a figure whom New York Times columnist Robert Lipsyte called “the most important sports activist of our lifetime,” one has to return to a time and place far from the global spotlight—the “colored” Southend section of East St. Louis, Illinois, just after World War II. Edwards describes his upbringing there as something below the black underclass— the “underfooting,” he calls it. His mother essentially abandoned the family when he was eight, simply walking off one day in 1951. His father, a former gang leader with a third-grade education who spent eight years in prison for burglary, tried to raise eight children on his own, but left them largely unsupervised. They survived in a house with no plumbing, where broken windows and holes in the roof allowed pigeons and rats free reign. They called it “the Fort.” Says Edwards: “I didn’t think I was going to get out of East St. Louis alive.” When he was twelve, his mother returned to take her children away from the squalor. But her oldest son chose to remain with his father, earning a scathing tirade. “I wish I’d never birthed you,” was the last thing his mother told him. “I wish you had died.” He saw her only once more in his life.

‘Theory and life had become fused into a single reality for me,’ Edwards writes in his autobiography, ‘and neither made any sense without the other.’ The father-son relationship was predicated primarily on the boy’s interest in sports, tenuous though it was. In fact, much of Edwards’s effort during his school years focused on convincing everyone—his father, classmates, and teachers—that beneath the brawn there was a brain. When he attended the newly integrated East St. Louis High School, he found that black students were ostracized from nearly every social and academic activity except athletics. So, reluctantly, Edwards participated in football, basketball, and track and field. By his senior year, he was one of the best discus throwers in Illinois. After a brief stint at a junior college in Fresno, California, Edwards earned a track scholarship at San Jose State, where he set a school discus record as a freshman but was kicked off the team as a sophomore after a disagreement with the coach devolved into a shouting match. He never picked up a discus again, but he kept his scholarship by playing basketball, fouling out of eighty-two of the eighty-six games in which he competed. “Edwards is an angry man,” Maya Angelou wrote in the foreword to his 1980 autobiography, The Struggle That Must Be, “and his anger reveals his humanity.”

He chafed at the racism he experienced in San Jose—both from the student body and the administration. But he also excelled, graduating with distinction as a sociology major in 1964 and earning a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship. Edwards opted to continue his studies at Cornell, largely because he viewed the late Robin Williams Jr. (a sociology professor from 1946 to 2003) as “one of the best people in the country in race relations and social stratification.” Edwards spent several weekends traveling by bus from Ithaca to New York City to hear Malcolm X lecture, an experience that led him to write his master’s thesis on Black Muslim families. He recalls entering a TV lounge at Cascadilla Hall in February 1965, just in time to hear white students cheering a news bulletin. Malcolm X had been assassinated.

Edwards came to realize that the racial tensions that had erupted in the mid-Sixties had, as he writes in his autobiography, “failed to penetrate the pastoral, ivory-tower milieu of Cornell.” Some of his professors, he writes, “were hostile to the very idea of any attempt on my part to synthesize my political and social concerns with my scholarly interests. But theory and life had become fused into a single reality for me and neither made any sense without the other.” He completed his MA in 1966 and returned to teach sociology at San Jose State, where there were twenty times as many foreign students as black students (most of whom were scholarship athletes). It was there that the disparate elements of his life—theory and reality, anger and education, sports and society—merged and crystallized into action.

With Ken Noel, a master’s candidate in sociology, Edwards documented racist practices on campus—in housing, athletics, academics, admissions—and realized that the sporting arena was the only place where blacks had any political leverage. When their attempts to meet with administrators proved fruitless, they decided to take their concerns public. At a rally attended by some 700 people in the late summer of 1967, Edwards declared that if various issues were not addressed, he would “mount a movement on campus to prevent the opening football game of the season from being played—by any means necessary.” California Governor Ronald Reagan threatened to ring the field with National Guardsmen and labeled Edwards a lawbreaker who was unfit to teach. Edwards’s response was that Reagan was “a petrified pig, unfit to govern.” In the end, the game was canceled, a first in major collegiate history, and the administration met most of the students’ demands. “So we had carried the confrontation,” Edwards wrote two years later in his book The Revolt of the Black Athlete. “But more than this, we had learned the use of power—the power to be gained by exploiting the white man’s economic and almost religious involvement in athletics.”

In 1968, Edwards formed the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) and advocated a boycott of the Mexico City Games. “Why should we run in Mexico,” he asked, “only to crawl home?” The OPHR presented a list of demands, including the removal of International Olympic Committee chairman Avery Brundage (whom they considered racist), the curtailment of participation by teams from apartheid South Africa and Rhodesia from all U.S. and Olympic athletic events, and the restoration of Muhammad Ali’s boxing titles, which had been stripped after he refused military service.

As the movement grew, Edwards delivered speeches at dozens of colleges. In the process, he became a target. He received hundreds of death threats. “KKK” was scratched into the trunk of his car. His two dogs were hacked to death. “Was I fearful? No, because fear immobilizes you,” Edwards says four decades later. “But I was supremely cautious and prepared.” Newspapers such as the Los Angeles Sentinel printed headlines like NEGRO HOT-HEAD THREATENS GAMES BOYCOTT. J. Edgar Hoover included him in the “Agitator Index,” sending a memo to his subordinates calling Edwards “a fanatic revolutionary.”

Edwards’s rhetoric did little to dispel that notion. In a statement published in the Saturday Evening Post, he declared that any black athlete who did not support the boycott was “a copout and a traitor to his race.” When South Africa was admitted to the Olympic Games (a decision soon reversed), Edwards announced plans for a second set of games to be held in Africa. “Let whitey run his own Olympics,” he said. Edwards calls his rhetoric the “necessary stridency of the era,” and it got results. After the OPHR called for desegregation of the New York Athletic Club and a boycott of a prestigious track meet it had held for nearly a generation, thousands protested outside Madison Square Garden during the meet and only a handful of black athletes showed up. Edwards declared that “the black athlete has left the facade of locker room equality and justice to take his long vacant place as a primary participant in the black revolution.” In a five-part Sports Illustrated series about the issue, Jack Olsen stated, “Like it or not, face up to it or not, condemn it or not, Harry Edwards is right.”

Not all African American athletes agreed with Edwards. Some figured it was their obligation to participate in a boycott; others wondered how much pride one can lose by emerging an Olympic champion. In the end, most of the OPHR’s demands were ignored and the boycott never happened, although Edwards’s primary goal—to dramatize the racial inequities and barriers confronting blacks in sport and society—was successful. It was decided that each athlete would choose a personal form of protest at the Olympics.

Edwards returned to Cornell to complete his PhD, moving into an apartment in Dryden. (FBI investigators followed.) He made plans to travel to Mexico City for the Olympics, until he was talked out of it for his own safety. When Smith and Carlos made their protest, Edwards was 2,300 miles away in Montreal. But another Cornellian did attend the Games—Bob Kane ’34, who was then secretary of the U.S. Olympic Committee. In an account written for the Cornell Alumni News a day after he returned home, Kane commented on what he called “the Smith-Carlos incident”: “We felt they had been embarrassing exhibitionists and had used one of the genuine peaceful forums of the world to demonstrate against an internal problem, but we were not inclined to be harsh. We felt they were taking orders. We planned to warn them and the rest of the team and state that a second incident would connote a conspiracy, and extremely tough measures would be taken.”

Pressured by Avery Brundage, the USOC suspended the men from the Olympic team and sent them home, where they were largely vilified. The Los Angeles Times described their protest as a “Nazi-like salute.” Time magazine showed the five-ring Olympic logo but replaced the motto “Faster, Higher, Stronger” with “Angrier, Nastier, Uglier.” But Smith and Carlos were heroes to many black Americans—and to many athletes around the world. Edwards was, too. In fact, he received a telegram from Cuba’s 400-meter relay team saying that they were dedicating their silver medals to him.

In the years that followed, the Olympics would become even more politicized. In Munich in 1972, Palestinian terrorists would cause the deaths of eleven Israeli athletes. In 1976, African nations would boycott the Games to protest apartheid. After President Jimmy Carter announced a U.S. boycott of the Moscow Games in 1980, Edwards said, “I find it ironic that twelve years after I was denounced for calling for a boycott of the Olympics, the president of the United States has called for a boycott—proving unequivocally that sports are indeed political.”

When Edwards returned to Cornell to pursue his PhD, he aimed to undertake a serious study of sport’s relationship to society without, as he puts it, “the fiery but shallow and ephemeral rhetoric of activist politics.” He wanted to be an educator, first and foremost—”inciting people to think.” Ironically, he arrived in Ithaca just in time to witness the April 1969 Straight Takeover in which African American students seized Willard Straight Hall and rumors swirled about an imminent armed counterattack. Edwards wasn’t involved in the planning, but after being asked for advice by some students in the Straight, he told them, “I would arm myself. If there’s going to be shooting, I would be doing some of it.” Thus came the spectacle of armed black students draped with ammo belts—and once again Edwards found himself in the midst of controversy.

Meanwhile, he was busy doing some wrangling of his own— with the sociology faculty, who compelled him to do three total revisions of his dissertation. The end product was a book, The Sociology of Sport, which launched an entire field of study and became his life’s work. Soon after, he received a job offer from the University of California, Berkeley, where he would have a long and tempestuous stay—including a seven-year struggle over tenure that earned national headlines. Eventually, the university reversed its decision to deny him tenure, and Edwards served as one of Berkeley’s most popular lecturers for thirty-one years.

He also became part of the very establishment he used to despise. Case in point: he has traveled to Virginia several times to serve as a diversity awareness consultant—for the FBI. But he insists that society has merely moved toward his way of thinking. Just visit the campus of San Jose State, he says, where there stands a statue of Smith and Carlos, fists upraised. “I’m saying essentially the same things now that I was saying then, only now they don’t call me a revolutionary and a radical,” he says. “They call me a consultant.”

Indeed, in 1986, he was hired by the NFL’s San Francisco 49ers (and later the NBA’s Golden State Warriors) as a consultant-mentor, advising professional athletes on everything from personal finances to race relations. His programs for handling player personnel issues were eventually adopted by the entire NFL, and Edwards continues to consult for both the 49ers and the league. In 1987, in the wake of former L.A. Dodgers executive Al Campanis’s firing for saying on “Nightline” that blacks “may not have the necessities” for management positions, Edwards began a five-year stint as special assistant to Major League Baseball commissioner Peter Ueberroth, who charged him with assembling a pool of minority applicants for managerial positions. Edwards’s first order of business? Hiring Al Campanis as an adviser. “If I’m going to teach a class on safecracking,” he explained at the time, “I’m not going to bring in someone who had their safe cracked. I’m gonna bring in the safecracker.” In 2000, Edwards even became a bit of a bureaucrat, taking a three-year position as director of the Oakland Department of Parks and Recreation.

Mainstream or not, Edwards remains visible. Whenever a story jumps from the sports pages to the front pages—when Michael Vick pleads guilty to running dogfights or Don Imus makes racist and sexist comments about the Rutgers women’s basketball team—he is the media’s man of choice for a comment. Edwards consistently trumpets his contention that sports success is overemphasized to black youths, while sports participation can be vital. “Sports may be the last handle we have on a lot of these kids,” he says, “and even that is starting to slip away.” Edwards points to numbers, such as the fact that a quarter of all black males between fifteen and twenty-nine are under the control of the judicial system and the frightening homicide rate of that same demographic. Citing the dramatic reduction in the number of African American baseball players, he offers this provocative thesis: the “golden age” of the black athlete, which lasted roughly from Jackie Robinson’s debut in 1947 to Michael Jordan’s retirement from the Chicago Bulls in 1999, is over. “We are simply disqualifying, jailing, burying, and leaving behind our black athletes, right along with our potential black doctors, black lawyers, and so forth,” he says. “And that tells us that something is critically wrong.”

China’s Syndrome

In 2007, Yang Chunlin, a former factory worker in northeastern China, collected 10,000 signatures after posting an online petition entitled “We Want Human Rights, Not the Olympics.” He was sentenced to five years in prison, one of dozens of journalists and bloggers who have suffered similar fates. In the wake of the Chinese government’s crackdown on critics as the Summer Olympics approach, commentators have wondered about the silence of the International Olympic Committee (IOC). “There were explicit expectations. The Chinese said they were going to improve human rights. But nobody’s held them to that, and in fact they’re rounding up dissidents,” says Adam Segal ’90, PhD ’00, senior fellow for China studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. “The problem is nobody wants to get backed into a corner by calling for a boycott. From the U.S.’s point of view, we have to work with China on so many other issues—nuclear North Korea, Iran, and Sudan. Nobody wants to threaten this leverage.”

Indeed, while IOC president Jacques Rogge has said that he has asked Chinese leaders to live up to their “moral pledges,” he insists that getting involved in a host country’s political affairs is “the line we do not have to cross.” Olympic committees in Belgium, New Zealand, and the Netherlands—and, until worldwide criticism sparked a reversal, Great Britain—have forbidden their athletes from opining on politics during the Olympics. With the Games once again emerging as a test of free speech on the world stage, will athletes follow the example of Tommie Smith and John Carlos and use them as a platform for politics? Harry Edwards, for one, believes it is a moral imperative. “If it were me, I would boycott the Games over the Darfur issue, but if they’re going to go to China to participate, then I think the athletes have some responsibility to indicate that they are dissatisfied with conditions there,” says Edwards. “To go to a place where human rights are being denied and to say nothing, at some level that makes you virtually complicit.”

Brad Herzog ’90 is a CAM contributing editor. In his book The Sports 100, he ranks Harry Edwards as the 93rd most important person in American sports history.