When Dean Smith was a young teen growing up in Baltimore, he’d sneak downstairs to watch a certain program airing on the local PBS station long after bedtime—a brilliant, wildly original show laden with Spam, dead parrots, silly walks, the Spanish Inquisition, and upper-class twits (though distinctly lacking in cheese). Guffawing over those episodes of “Monty Python’s Flying Circus”—and later acting out scenes with classmates at his Catholic high school, where the “dead bishop” sketch seemed particularly naughty—the young Dean never imagined that decades later, he’d be sharing a stage with a member of that antic and erudite troupe.

Lindsay France/UREL

But in September 2017, Smith—now director of Cornell University Press—appeared in Bailey Hall with Python legend John Cleese. Smith had prepped for the event for months, rewatching every Python show and movie and reading all of Cleese’s writings, up to and including an obscure essay about cricket. For two hours, he interviewed Cleese about everything from Python’s fiftieth anniversary (coming in 2019) to his fraught relationship with his mother to the relative merits of cats over children. “The great thing about realizing that things are completely hopeless is that you start to relax,” Cleese observed at one point. “Next, your aims become more realistic. You say, ‘I’ll tell you what—instead of changing society, I’ll just be nice to a dozen people instead.’ Because that’s achievable.”

In advance of the talk, Smith had met with Cleese to go over the topics he planned to cover. (To be precise, Smith went to his room at the Statler for a pre-show chat; Cleese answered the door in his boxer shorts and jovially offered him a cup of coffee.) “We agreed to start with Python,” Smith recalls. “That’s always the elephant in the room. He kept saying, ‘People want to know about Monty Python.’ I don’t think he wants to do a lot of talking about that, usually. I think he wants to talk about scholarship. In the time that I spent with him, my sense was that his mind is constantly, endlessly pursuing and devouring content of all kinds. As much as he can get his hands on, he likes to process and think about. Whatever the percentage of the brain that we’re supposed to be using on average, he’s using more of it.”

In October, the Press published Professor at Large: The Cornell Years, a chronicle of Cleese’s major appearances on the Hill over the past two decades. From 1998 to 2006, Cleese was an A.D. White Professor at Large, serving a six-year term plus a two-year extension; since then, he’s been the Provost’s Visiting Professor, making regular visits to campus to give public talks and to work with faculty and students. The book comprises edited transcripts of seven events, including the Smith interview, a sermon in Sage Chapel, a talk on religion inspired by the controversial Python film The Life of Brian (about a hapless fellow who gets mistaken for a messiah), and a deep dive into screenwriting by Cleese and two-time Oscar winner William Goldman (All the President’s Men; Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid). “It’s completely nonlinear—it’s not your typical book acquisition,” says Smith. “But I think it’s an important part of Cornell’s history, and it presents a different side of John Cleese. People have talked about him being a scholar or being interested in intellectual pursuits, but this is it right there.”

The book project was spearheaded by Gerri Jones, former administrator of the A.D. White Professors program, who had continued to handle logistics for Cleese’s campus visits. Jones, who worked with Cleese on Cornell’s behalf for nearly two decades, kept an informal archive of his talks. “She had a shopping bag of CDs of audio recordings,” Smith says, “and a printout of the speech in Sage Chapel.” Jones typed up the transcripts, which went to an editor that Cleese works with on his literary projects, then to the press’s copy editors, then to Cleese for final approval. Sadly, Smith notes, Jones didn’t live to see the manuscript published; she passed away in August, of complications of leukemia. “She fiercely loved John Cleese,” Smith says, “and she really made the book happen in a behind-the-scenes way.”

As of late August, the Press had pre-sold 3,000 copies of Professor at Large—which may seem modest by Grisham terms, but which Smith notes is more than ten times that of the publishing house’s typical scholarly monograph. While Cleese’s next Cornell appearance hasn’t been announced, his relationship with the University is ongoing, and a book-related event in New York City is set for November (see below). As Cleese said at the end of the Bailey chat: “I’m absolutely delighted at the thought of being able to come back to Cornell on a regular basis and stir things up.”

CU Press’s Dean Smith (left) interviewing Cleese in Bailey Hall in fall 2017; other than some empty seats at the fringes, the house was packed. Chris Kitchen/UREL

‘Democracy Gone Mad’

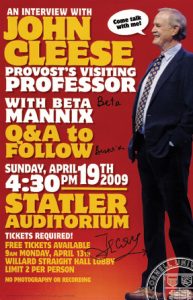

In a condensed excerpt from Professor at Large—chronicling an event in Statler Auditorium in April 2009—Cleese and CU management professor Beta Mannix chat about Python’s group dynamics, how Brits handle anger, and much more

MANNIX: Let me ask you a little bit about how you got started doing what you’re doing, which wasn’t a particularly straight path. You started off going to a fairly well-respected prep school and you took your A levels, which we think of as sort of advanced tests, in things like mathematics, physics, and chemistry. You taught science [and] history. You went to Cambridge. You have a degree in law. And then, life took sort of a different route for you.

CLEESE: Well, how many people really know what they want to do? I’ve always been amazed that some people know what they want to do. All I know is that I want to do the next project. I think, deep down, psychology has always been my fascination. I think the most interesting thing in the world is how this thing works [he points to his head] and why we do the things we do.

MANNIX: When you decided law wasn’t for you, you went to write for the BBC. So much of your work is writing, really.

CLEESE: That’s right. I always think of myself as a writer-performer. In other words, I write the thing and then I perform it. But for me, the interesting bit is writing it.

MANNIX: Some of the earliest work you did was with Monty Python—Graham Chapman, Michael Palin, Eric Idle, and the Terrys—and you’ve really made no secret that you were not necessarily one big happy group of guys. You really didn’t get along that well.

CLEESE: Well, think about it. You can all think of bands, and how many of them have stayed together? A very special, select group. But on the whole, they break up because there are always tensions in any group of human beings. Diversity often means conflict. So it’s interesting that we are talking about the Python group because the funny thing was that it was democracy gone mad. I mean, no one was in charge, and it is very unusual, I think, to get a good group of people working together satisfactorily when no one is in charge.

MANNIX: You obviously are brilliant at physical comedy. And I’m sure I’m not the first person who’s noticed you often played the angrier person in the group—with a sort of seething rage that’s bound to burst out.

CLEESE: Well, I think the English are terribly funny when they’re angry because they absolutely don’t know how to do it. There’s an episode—Connie, who was my first wife, is American. In fact, most of my wives have been American, as far as I can remember. Connie and I wrote an episode called “Waldorf Salad,” which is all about the fact that Americans know how to complain and the British don’t. The British just sit there, as happens in that episode, saying, “Isn’t it awful?” and, “This food is dreadful,” and, “They haven’t cooked the potatoes.” And somebody comes up and asks, “Is everything all right?” “Very nice, indeed, thank you.” All they then do is never come back. The English are very, very poor at complaining. They equate being angry with losing their temper. And it’s absolutely nothing to do with losing one’s temper. Anger is a kind of energy, which, if you can control it, gets a lot done. If you lose your temper, you dissipate the anger and make a bit of a fool of yourself. In England, to be angry, to lose one’s temper, is almost a loss of face. It’s very strange, a huge cultural difference.

MANNIX: When you talk about Monty Python, you talk about democracy gone mad. Was there somebody who eventually was able to take control of that group to make the decisions?

CLEESE: Well, what really happened was that there were two people in the group who were slightly dominant. There was me and there was Terry Jones. He and I used to lock horns and disagree on almost everything because I was sort of snotty and superior and using sort of a cold, rather sarcastic intellect. And he was all Welsh fervor. He felt strongly about absolutely everything, which infuriated me because I didn’t mind him feeling strongly about some things, but he felt strongly about everything, and he had to have his way about everything. So we would lock horns, and the other four, to switch analogy, would get on the scales and, because we were balancing each other out, the others would get on and then the majority view could pretty much prevail.

The extraordinary thing was, if you want to understand the Python group, we were six writers who performed our own material. All the squabbles and fights were about the material. They were never about the casting. Which is weird, isn’t it? Because you’d think we’d each want the best part—but we didn’t. Once we’d written the material, we knew perfectly well that Graham should play that, Michael should play that . . . It was obvious to us.

MANNIX: To go back to your education in science and law, and I think you studied religion as well, right? Were all those things important pieces in your ability to write these unbelievably hysterically funny sketches? Where did all that come from? Or was it just a waste—was the education just a waste?

A poster for Cleese’s 2009 event, signed by him to Mannix.Watch here

CLEESE: No, it did teach me to think, but when you look back on it and see what you learned—for example, take trigonometry. It may have been reasonably good for training my mind, but remembering that the sine is the perpendicular of the hypotenuse and all that kind of thing was not of great value to me in my later life. I was not taught anything about health or about how the human body worked, which would have been really useful. I was taught nothing about psychology, which would have been fascinating. But the important thing was that I was taught to think analytically.

But the interesting thing is that if anyone wants to get into an MBA program, all the questions that they’re asked are about critical analytical thinking. There will not be a single question to test your creativity. And yet, if you think of all the people who have really made a difference, like Edison, Einstein, Steve Jobs—these are people who were immensely creative. Now, why would it be that you can get into an MBA program without anyone testing your creativity or making any attempt to suggest how you could become more creative? Do you realize how insane that is? It’s a terrible, insane blind spot.

MANNIX: So where do you learn that? How did you learn that?

CLEESE: Well, I learned it because when I was at Cambridge, there was a club called the Footlights, which is like the Hasty Pudding at Harvard, and I joined it. There was no drama department at Cambridge. You see, I’ve never had a drama lesson in my life. I’ve simply watched people who were good and stolen from them! So there was a very interesting mix—there were classicists and historians and scientists and engineers. And there was also a mixture of social classes. We had one or two lords and several people from very poor working-class homes. And they’d all come into this club room where you could get lunch and a drink in the evening, and there was a little stage. And I loved being there. The price of being a member was that you had to produce a sketch and perform in it now and again. It was there I discovered that, if I was given a sheet of paper, I could sit down and after two and a half hours I would have written something which had a very good chance of making people laugh. I suddenly discovered that I had this creative ability.

And yet, my entire education from the age of six to twenty-four—I was very old when I left Cambridge—I went through that entire period without a single teacher ever telling me that I was, in any way, creative. I think the problem with the educational system is that, by and large, kids are allowed to paint when they are young, but after that stops, it’s all about developing what you can refer to as the left brain, and very little of it is about the right brain. I believe that a pretty happy and successful life has to do with getting a balance between the two.

Excerpted and condensed from PROFESSOR AT LARGE: THE CORNELL YEARS by John Cleese, published by Cornell University Press. Copyright © 2018 by Cornell University. All rights reserved.

During environmental artist Andy Goldsworthy’s time as an A.D. White Professor in the early Aughts, he created numerous works on campus, including this leaf installation. Johnson Museum of Art

Great MindsPast and present A.D. White profs include many famous namesNatalie Angier Michelangelo Antonioni Norman Borlaug Jacques Derrida Andy Goldsworthy Jane Goodall Mae Jemison,MD ’81 Wynton Marsalis Barbara McClintock 1923, PhD ’27 Toni Morrison, MA ’55 Octavio Paz Oliver Sacks Kip Thorne Eudora Welty Wendy Wasserstein |

Visitors Welcome

The A.D. White Professors-at-Large program brings global thought leaders to the Hill

In Cornell’s early days, founding president Andrew Dickson White feared that given Ithaca’s isolated location, the new University and its scholarship could become overly provincial. One remedy, which he promoted and facilitated, was a regular roster of visiting professors from far and wide, whose contributions would benefit the resident faculty. “Their views would be enlarged,” he said, “their efforts stimulated, their whole life quickened.”

In 1965, Cornell’s centennial year, the University inaugurated a formal program of visiting professorships, named in White’s honor. Since then, more than 160 distinguished scholars, artists, and scientists from a vast array of fields have served as A.D. White Professors-at-Large. Each year, a faculty committee considers a list of candidates nominated by Cornell professors and others on campus, who submit proposals on how the individual would enrich teaching and scholarship; its selections must be approved by the president as well as a vote of the Board of Trustees. Up to twenty people can hold the professorships at any given time, typically serving six-year terms (which can be extended an additional two years, as in the case of John Cleese).

Each year, the program sponsors up to six visits, with the professors receiving a per diem of $1,000, plus reimbursement of travel costs. Most stay at the Statler or on West Campus, the latter offering more direct interaction with students. “To me the key element of the A.D. White Professorships is presence,” says theatre professor David Feldshuh, who served two three-year terms on the selection committee and is now its chair. “There is something about a person’s presence in your environment that can’t be replicated, regardless of communication technology. Their presence allows for small, unforeseen opportunities—and even accidents—that create new energy, new vitality, new insights for the campus and the community.”

Currently, there are seventeen A.D. White Professors. They include a Chinese multimedia artist, an environmental journalist, a Mumbai-based architect, an evolutionary biologist, and a French philosopher who’s a leader in science and technology studies. Those who’ve made recent campus visits include jazz great Wynton Marsalis, who gave master classes and concerts last spring, and Duncan Watts, PhD ’97, a pioneer in the field of network theory, who gave a public lecture this fall.

“You end up having people who are enormously accomplished, and enormously interesting,” Feldshuh says. “It might be someone interested in cheetahs, or who has saved the environment of a city in Texas, or who helped create the legal system in South Africa—I could go on and on. Invariably, what I get from watching the A.D. White Professors live in this environment for a week or two is the joy they have in the activities to which they’ve dedicated their lives. It just reminds you of how much fun it is to learn.”

While most A.D. White Professors serve six-year terms, that has sometimes varied due to individual circumstances.