The October 1967 issue of the Cornell Alumni News had a one-page article titled “Wingate’s Cahows.” In the story, Garrett Byrnes described the efforts of thirty-two-year-old David Wingate ’57 to restore the population of the Bermuda petrel, also know as the cahow, which was thought to be extinct before its rediscovery in 1951. Wingate, then a teenage amateur ornithologist, had been lucky enough to take part in the expedition that found the living cahows. That serendipitous moment spawned a lifelong obsession.

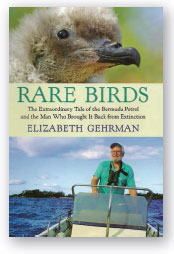

The story of Wingate’s campaign to save the cahows and restore their native habitat is told by journalist Elizabeth Gehrman in Rare Birds: The Extraordinary Tale of the Bermuda Petrel and the Man Who Brought It Back from Extinction. The book’s genesis was Gehrman’s 2009 trip to the island country to write a travel story for the Boston Globe. While there, she was introduced to Wingate —who was, she says, “like an open book, happy to share everything about the cahows.” Fascinated by his account, Gehrman returned to Bermuda more than a dozen times. Her narrative focuses on the difficult work needed to increase the population of the birds—now firmly re-established—intertwined with a history of Bermuda, which was discovered and colonized by the English 400 years ago, and the story of Wingate’s life.

After graduating from the Arts college with a degree in zoology, Wingate returned home to Bermuda and became a conservation officer. He spent much of his time protecting the burrows where the cahows lay their eggs and restoring the native vegetation on Nonsuch, one of the small islets where they nest. Nonsuch became his home in 1962, and over the ensuing decades Wingate planted thousands of trees, bushes, and flowers in an effort to return it to its pre-colonial state. Despite rough weather, bureaucratic hurdles, family tragedy, run-ins with the U.S. military, and a bad back, he persevered; today Nonsuch has been largely returned to its virgin state thanks to his work. Seventy-seven years old and officially retired, Wingate remains dedicated to conservation in his homeland—and to protecting the ocean-going birds that inspired his career. “If you just give the natural world a little help, it will bounce back,” he told Gehrman. “That is the message of hope that I’ve gotten out of my experience with the cahows.”