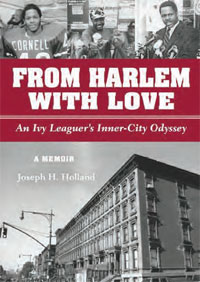

Activist entrepreneur Joe Holland '78, MA '79, reflects on his eclectic career—and his august father, Brud Holland '39, MS '41—in From Harlem with Love

Activist entrepreneur Joe Holland '78, MA '79, reflects on his eclectic career—and his august father, Brud Holland '39, MS '41—in From Harlem with Love

In his recently released memoir, Joe Holland '78, MA '79, notes that as an English and history double major on the Hill he was introduced to the poetry of the Harlem Renaissance. The opening line of his favorite poem ("Harlem") by his favorite poet (Langston Hughes) consisted of six words that haunted him: "What happens to a dream deferred?"

Holland's great-great-great-great-grandmother had been a slave in Georgia. During Reconstruction, his great-great-grandmother had worked as a chambermaid in an Atlanta hotel, where she was raped by a guest. His great-grandmother was one of the early graduates of Spelman College. And his father, Jerome "Brud" Holland '39, MS '41, had been a pioneer. The only one of thirteen children in his family to attend college, he worked his way through Cornell (shoveling coal into a fraternity house furnace) and earned two-time All-American status on the gridiron. Although the color of his skin precluded offers from pro teams and interviews with corporate recruiters, he eventually became president of two universities, U.S. ambassador to Sweden, chairman of the American Red Cross, and the first African American on the board of the New York Stock Exchange.

Joe Holland followed in his father's footsteps as an All-American. He also excelled academically, writing a senior thesis entitled The Procrustean Bed of the New South: The Higher Miseducation of the American Negro. So when he opted for Harvard Law School over a possible free agent stint with the Dallas Cowboys, his parents found it sensible. But they were less sanguine when, a few years later, he told them he was going to take his law degree to Harlem. The once-thriving neighborhood had been dealt a severe blow by the Depression and the decades that followed. An exodus of middle-class blacks had left it as an embodiment of urban blight—as Holland writes in From Harlem with Love: An Ivy Leaguer's Inner City Odyssey, "a miasma of intractable poverty with only distant memories of inspired poetry."

Believing that he was squandering opportunities that his ancestors never had, Holland's parents feared that the dream deferred would be their son's. "For a silver-spoon member of the black elite like me," writes Holland, "the choice could not have been starker: a smooth transition to New York's downtown white upper class versus a defiant detour to its uptown black underclass." But he was drawn to what he viewed as Harlem's unrealized potential, describing it as "a Third World colony on the most prosperous island in the world."

Throughout From Harlem with Love, Holland weaves a cultural history of the neighborhood—movers and shakers, artists and architecture, peaks and valleys, causes and effects. "I wanted to tell two stories—my story and Harlem's story," says Holland, a member of the Cornell Athletic Hall of Fame who served on the Board of Trustees for twelve years. He arrived in Harlem envisioning revitalization based on bolstering "community-based institutions through which the human and financial resources can flow toward individual achievement."

Holland's career as an activist entrepreneur began with a solo law practice, his first clients being the daughters of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. He became legal counsel to Christ Community Church of Harlem and was ordained an assistant pastor. In 1986, he founded Harlem's Ark of Freedom (nicknamed Hark), a nonprofit that operated Harkhomes, a fifteen-bed homeless shelter that began in a church basement. His philosophy was one of "holistic housing," which included teaching life skills as a first step toward restoring the whole person. He also co-founded Beth-Hark Crisis Center for addicts and ex-offenders. Then, in part to find employment for many of the shelter residents, he launched a series of small businesses—a restaurant, the Harlem Travel Bureau, even a Ben and Jerry's ice cream shop on 125th Street. For the latter, Holland invented his own taste-of-Harlem flavor, Bluesberry. "Music has been a big part of Harlem's character," he says. "I was thinking poetically and practically."

Holland also wrote plays; Cast Me Down, about Booker T. Washington's time at the Tuskegee Institute, had a brief run off-Broadway, and Homegrown, based on his experiences with Hark, was staged at the National Black Theatre. His business enterprises had longer runs—but he admits that in the end they were more charitable than profitable, in an environment where the profit potential was low and the risks were high. "I knew from my studies that there were problems in Harlem," he says, "but I had no idea how profound and intractable they were until I arrived."

Holland also wrote plays; Cast Me Down, about Booker T. Washington's time at the Tuskegee Institute, had a brief run off-Broadway, and Homegrown, based on his experiences with Hark, was staged at the National Black Theatre. His business enterprises had longer runs—but he admits that in the end they were more charitable than profitable, in an environment where the profit potential was low and the risks were high. "I knew from my studies that there were problems in Harlem," he says, "but I had no idea how profound and intractable they were until I arrived."

In the Nineties, while still living in Harlem, Holland broadened his professional horizons. He served two years as New York State Housing Commissioner under Governor George Pataki, joined a White Plains law firm specializing in insurance defense, and traveled the country as a spokesperson for the GTE Academic All-America program. When his third child was born in 2000, he moved his family to suburban Yonkers, but his professional ventures returned to uptown Manhattan. He renewed his Harlem law practice and made waves as a real estate developer, assisting in the creation of two luxury condo buildings in the neighborhood.

But Holland believes his most lasting legacy may be the collection of life lessons he developed over the years while trying to help his neighbors help themselves. He has compiled them into a DVD series called "Holistic Hardware," which taps the aspects of his varied career—biblical parables, dramatic sketches, inspirational testimonies from Harlem residents—as tools for personal transformation. His workshops and seminars based on the concept have taken him as far as Liberia, where the Joseph Holland Christian Institute serves as a residence and school for the orphans of the country's civil war.

Yet Holland's heart remains in Harlem, which was enjoying another Renaissance until the recent recession. Although the neighborhood may be down, he says, it will never be out. "Harlem," he writes, "proves that as long as one holds on to it through the trials and travails, it evolves into the sustaining hope that, some day, the dream will no longer be deferred."

— Brad Herzog '90