Cornell senior Rick Ledbetter is an indifferent student, a shameless womanizer, and a wannabe war hero. It’s the spring of 1967, and the faraway conflict in Vietnam is increasingly dividing East Hill. Some students, like Rick, are true believers eager to battle the communist threat. Others are using every connection and pretext they can muster to avoid being drafted as graduation looms. And many, including Rick’s younger brother Tommy, are passionately involved with the antiwar movement—holding protests in front of Willard Straight Hall, organizing marches off campus, and risking criminal charges by burning their draft cards.

Rick is the narrator and protagonist of And the Sparrow Fell, a new novel by former U.S. Congressman and longtime author Robert Mrazek ’67. And to some extent, he’s Mrazek’s alter ego: Rick’s experience in being disillusioned by America’s involvement in Vietnam—going from gung-ho Navy enlistee to embittered antiwar protester—mirrors Mrazek’s own. “I had those romantic illusions that Vietnam was worthy, and it wasn’t; it was built on a lie,” says Mrazek, chatting with CAM at his home in Ithaca early in the summer. “It divided our country in ways we still haven’t recovered from.” He says that part of his motivation in putting it out now—a half-century after the events it covers—is that the issues it raises remain urgently relevant. “We could have another Vietnam or Iraq, in which an arrogant group of people in Washington decide that we should invade another country where we have no conception of its culture or history,” says Mrazek, whose son joined the military after 9/11 and served in Iraq. “Unlike during Vietnam, we no longer have the draft. I think young people should be aware of what can happen to them if they volunteer for an army directed principally by men in Washington who are ready to send them to war, but most of whom never went to war themselves and have no conception of its cost.”

Published this month by Cornell University Press under its Three Hills imprint, And the Sparrow Fell was five decades in the making: Mrazek began the first draft after being partially blinded in a freak accident in Officer Candidate School. (He describes it, with a rueful laugh, as “just about the least heroic thing you can possibly imagine”: he was standing in formation when a lawnmower struck a metal sign and a flyaway shard pierced his right eye.) While recuperating in a military hospital, he met injured veterans who exposed him to the realities of the Vietnam conflict—which stood in stark contrast to his long-held notions of honorable glory in combat like his hero, John F. Kennedy, who commanded a PT boat in World War II. “In the hospital, I saw what the war had done to these young men—psychically, physically, the way it had corroded their spirit,” says Mrazek, who dedicated his book to his late first wife and to classmate Robert Porea ’67, a helicopter pilot who died on a rescue mission in Vietnam. “It was only then that I realized the war was a horrendous mistake.”

In the novel, though, Rick experiences the horrors of war first-hand. Serving on a swift boat in the Mekong Delta—the job for which Mrazek had been training—he not only suffers a devastating injury in battle, but witnesses the horrific deaths of friends and shipmates. In the hospital, like Mrazek in real life, he comes to realize not only that the war is ill-conceived, but that the burden of fighting it falls disproportionately on the less affluent. At a pivotal moment, Rick writes a letter to his brother Tommy, admitting that he’d been right to resist the war: “I wrote to him about the boys in the dirty surgery wards—kids who had never been away from home before who found themselves sent off to a war they didn’t understand and never would. Iowa farm boys and Alabama rednecks, white high school dropouts from Long Island, and South Los Angeles black kids who got high school diplomas from schools without teachers, the ones who couldn’t afford a college deferment or weren’t able to figure out all the clever ways to avoid the draft. All the ordinary young men who, when called to serve, did so without complaint. They lined up and went.”

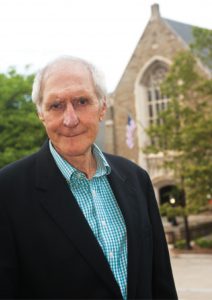

Bob Mrazek ’67

Photo: Thomas Hoebbel

Like his protagonist, Mrazek grew up on Long Island and was a government major on the Hill; also like Rick, he was skilled at tennis and spent more than a few undergraduate hours at the poker table. But Sparrow is no self-portrait. While Mrazek had what he terms a “ ‘Leave it to Beaver’ childhood,” Rick’s Gold Coast family is as wealthy as it is dysfunctional, torn asunder by alcoholism, adultery, and bitter arguments. And when we first meet Rick, Mrazek admits, he’s a “total jerk”—an irresponsible, egocentric misogynist who shamelessly tries to steal his kindly brother’s girlfriend. “My biggest fear in wanting a broad audience for the story is the fact that he is detestable in certain ways, but I came to the conclusion that I needed that character arc,” he says. “He does say from the first page that he’s going to tell the story the way it happened, even though it’s very ugly. And I think he can be funny; I hope the originality of his voice relieves some of the dislikable aspects of his personality.”

Sparrow is the first original novel ever published by Cornell University Press—and for Big Red readers, many of its pleasures will lie in its portrait of undergraduate life on East Hill in the late Sixties. Mrazek weaves in familiar locales on campus and off, from the Straight and Sage Chapel to bygone student haunts like the Chapter House, the Royal Palm Tavern, and Obie’s Diner (home of the famed Bo Burger). He also includes characters from real life, including Daniel Berrigan, the Jesuit priest and renowned antiwar activist who was an assistant director at Cornell United Religious Work. Popular history professor Walter LaFeber makes an appearance (though he’s renamed LaFrance); in a blurb for the book, LaFeber calls Mrazek’s novel “as wonderful and accurate [an] account of Cornell in those important years as anything I know.”

Mrazek’s bibliography features several works of nonfiction, including the World War II combat histories A Dawn Like Thunder and To Kingdom Come. He has written thrillers including Valhalla and The Bone Hunters, which follow the sleuthing adventures of a female archaeologist and a retired Air Force general. His first big hit was Stonewall’s Gold, a 1998 novel that won the Michael Shaara Award for Civil War Fiction and was re-released as a Reader’s Digest condensed edition. Last month, the mystery imprint Crooked Lane published Dead Man’s Bridge, the first in a planned series about a disgraced former Army officer who solves crimes in an Upstate New York college town.

Mrazek with his son during his days in Congress

Photo provided

But before embracing the creative life, Mrazek had a prominent career in politics. A Democrat, he served five terms in the House of Representatives starting in 1983, becoming the rare freshman to sit on its Appropriations Committee. During his time in office, he sponsored several noteworthy bills including the Amerasian Homecoming Act, which allowed thousands of Vietnamese-born children fathered by American servicemen to emigrate to the U.S., and the National Film Preservation Act, whose provisions included establishing the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry. (His tenure in D.C. informed The Congressman, a 2016 film he wrote and co-directed that stars Treat Williams as a politician at a personal and political crossroads.) While planning a run for the Senate—Mrazek aimed to unseat Republican Alfonse D’Amato—he became embroiled in a 1992 scandal involving the House Bank: it came to light that the bank had a long-standing policy of honoring members’ overdrafts, which comprised thousands of checks in a single year. Voters were outraged, and dozens of Congressmen lost their re-election bids or opted to retire; Mrazek, who’d been named on the House ethics committee’s list of the main offenders, opted to bow out of the Senate race. “It hurt at the time,” he says, “but there were compensations—and one of them was saving my life.”

As he explains: after leaving politics, he finally had time to undergo surgery to correct a deviated septum—and in the process, doctors discovered an egg-sized tumor at the base of his skull. Although not malignant, it was still life-threatening and had to be removed; the operation lasted twenty-one hours, and Mrazek still bears a prominent facial scar from the procedure. “Life is full of these crazy intersections,” observes Mrazek, who splits his time between Ithaca and an island off the Maine coast. “And it turned out that I loved the writing life. It’s diametrically opposite to the public life, when I would see hundreds of constituents in a typical weekend. Now it’s just me and my laptop.”

Senior Spring: An excerpt from Mrazek’s novel

For me, the vanguard of the campus revolution arrived at Cornell on a raw morning in March 1967. At least, that was the first time I encountered it. The SDS, or Students for a Democratic Society, had probably been drafting their manifestos for months, but I hadn’t heard about it.

It was snowing again, another blast of arctic wind that filled the air with ice particles. Your typical Ithaca spring. It was around seven in the morning. In those long upstate winters it was still pitch-black then, but you could feel the place begin to come alive in the dark like a slumbering giant.

Most of the students seemed to be wired into the same natural energy source. As if in harmony, lights would begin winking on in the Baker Dorms and University Halls. In concert, an army of undergraduates would begin shambling into steaming shower rooms before putting on a double layer of winter clothing. With the first sickly rays of dawn peeking over East Hill, they began converging on the campus from every direction. Filled with determination, they fanned out to conquer their twenty-four-credit-hour course loads or to discover a new galaxy in the universe.

After almost four years, my academic career was finally coming to a close. That morning, my athletic career was ending too. I was already late for a meeting with Fred McKinlay, the coach of the varsity tennis team.

The windswept snow peppered my face like birdshot as I headed toward the suspension footbridge that crosses over one of the two-hundred-foot-deep gorges cutting through the Cornell campus. Unlike the students walking along beside me, I had just left the smoky warmth of a marathon poker game at the Seal and Serpent house. We had been playing for thirty hours and I was practically out on my feet, but eight hundred dollars richer.

Halfway across the bridge, I glanced down into the cataract of black water raging through the gorge and remembered the day when Tommy and I had almost drowned. That started me thinking about him, and whether he was still enjoying his sophomore year. Although I hadn’t seen him in months, my mother wrote that he had decided to major in religious studies and was planning to attend divinity school.

Coach McKinlay was already in his office at the tennis complex when I arrived. The green-painted concrete block walls were covered with photographs of the players he had coached over his long career, mostly guys with hair the length of toothbrush bristles wearing madras sport coats and white bucks. There were also pictures of Fred competing against the best players of his era like Pancho Gonzalez and Ken Rosewall. Now he prided himself on turning out players with his own brand of hustling play.

That morning he looked like he was nursing a bad stomachache. I interpreted it to mean he had finally decided to kick me off the team. What he didn’t know was that I was looking forward to it. After playing tennis competitively since I was five years old, I had as much interest in it as I did in reading Nancy Drew.

“That’s some tan for Ithaca” were his first words as I sat down in the molded plastic chair across from his desk. I had recently returned from a quick trip to Nassau but knew better than to respond.

“You think I’m a stupid jerk, don’t you?” Fred demanded.

“No, Coach,” I said.

“Don’t patronize me,” he came back. “I’ve known you for four years.”

He ran his fingers through his thinning gray hair and gazed up at the sainted players’ pictures on the wall. That seemed to give him the courage to continue.

“You’re hurting the team, and I can’t allow that. I’ve given you every chance to redeem yourself, and you’ve squandered them all.”

“I know,” I said. “I’m sorry, Coach.”

Down the hallway, I could hear the team starting to hit on the practice courts.

“You’re not a natural like Dave but you know how to win, how to compete. You could be the best player in the Ivies and well beyond that if you really applied yourself.”

Dave had played first singles at Cornell for three years. At one point, he was ranked as one of the twenty best college players in the country.

“I’m also fully aware of what your mother’s family has done for this university—and for the tennis program,” he said finally.

My mother’s name was engraved over the entrance to the new university courts. That was the only reason I was still on the team.

“So,” he began, and stopped again.

I started to worry he was about to give me another shot.

“I haven’t had a chance to practice as much as I would have liked, Coach,” I said. “I’m putting a lot of effort into my course work right now. I need to graduate to qualify for Naval Officer Candidate School.”

His hooded eyes got even narrower.

“What a load of crap,” he said. “Like the time you came in here sophomore year to tell me you had broken your arm over Christmas vacation so you couldn’t practice. You remember that? Except that one of your teammates saw a vet student over at the Veterinary School putting on your cast. As of today, you are no longer a member of this team.”

I smiled to show him there were no hard feelings.

“You’re happy about this, aren’t you?” he said.

“No, Coach,” I said.

“Get the hell out of my office.”

It was still snowing hard as I made my way across the Arts Quad toward Willard Straight Hall. Earlier that month I had rented one of the alumni guest rooms on the top floor to take much-needed naps after poker games. Having my monthly allotment of Grandpa Sprague’s trust made things a lot easier.

“The Straight,” as the Cornell student union is called, is a stone building slightly larger than Grand Central Station and built like a Crusader fortress. It holds two cafeterias, including the Ivy Room, where students gather to hang out, along with a warren of club and study rooms, innumerable fireplaces, a movie theater, gaming rooms, and the campus radio station, WVBR.

I was crossing the promenade leading to the big double entrance doors when I encountered the forward elements of the campus revolution. About a dozen people were clustered around the doors. They were all wearing red armbands. A girl in an army helmet had started to loop a long length of chain through one of the door handles. As I attempted to open the other door, a guy with shoulder-length hair and a scraggly beard stepped around me. He passed the chain through the second handle and padlocked it.

“This building was just liberated in the name of Students for a Democratic Society,” he declared after turning to face me.

He was wearing what looked like a red granny dress trimmed at the ankles over dirty chinos and desert boots, and he reeked of body odor. Be tactful, I remember thinking. This guy’s got the keys to the padlock. He can’t help being a complete asshole.

Before I could tell him how much I respected his Stalinist idealism, he looked up at the small crowd behind me and announced, “Today, we are demanding that the university give all course and curriculum control to the SDS Student Coordinating Committee. Until they meet this demand, the Straight is shut down. Totally.”

My reply just slipped out.

“Look, shithead, I have an important appointment with my faculty adviser in there.”

“You’ll have to conduct university business some-where else,” he said, sneering.

Two other guys dressed like him began rolling empty oil drums across the promenade toward the entrance. Behind them came two more carrying thick planks of pine lumber.

“Who phoned the Syracuse TV stations?” I heard the first one call out.

A timid-looking girl wearing combat fatigues checked a batch of notes attached to her clipboard.

“I asked Arnie to do it, but he told me that Jody told him that the People’s Action Council was in charge of all media contacts and so Jody said she would do it.”

“Jody? Jody’s a freak!” he shouted angrily.

That was my introduction to SDS, but I was too tired to give it further thought at the time. Walking around the building to the back entrance, I discovered that it wasn’t padlocked yet. I made it up to my alumni room and sacked out for the rest of the day.

I was crossing the promenade leading to the big double entrance doors when I encountered the forward elements of the campus revolution.

Excerpted from And the Sparrow Fell by Robert J. Mrazek, published by Cornell University Press. Copyright © 2017 by Robert J. Mrazek. All rights reserved.