“I’m probably the only ornithologist on a cereal box,” Steve Kress, PhD ’75, notes with a chuckle. “But not many cereals are named after a bird.”

“I’m probably the only ornithologist on a cereal box,” Steve Kress, PhD ’75, notes with a chuckle. “But not many cereals are named after a bird.”

The critter in question is the puffin. There’s the kind that a natural foods company sells as crunchy “pillows” in flavors like cinnamon or peanut butter — and the feathered ones that Kress, a teacher and researcher at the Lab of Ornithology, has spent more than four decades restoring to a small island off the coast of Maine. The two come together on boxes of Barbara’s Puffins, which promote Kress’s conservation work and feature a photo of him in an iconic pose: standing on a rocky shore, his white beard and tartan tam-o-shanter cap lending a timeless, nautical air. Naturally, he’s holding a puffin (of the avian variety) — the orange-beaked creature known as “the clown of the sea.”

These days, Atlantic puffins are the unofficial mascots of the Maine coast, their endearingly goofy images adorning myriad businesses and T-shirts up and down the popular tourist route. It’s striking to think that just over a century ago, they were all but erased from these waters — hunted for their eggs, meat, and feathers. While puffins aren’t an endangered species — they’re abundant in other parts of the world, including Canada and Northern Europe — as of 1901 America tallied only a single breeding pair, on Maine’s Matinicus Rock. Now hundreds of pairs nest on several small, rocky islands in the Gulf of Maine, where the National Audubon Society’s Project Puffin maintains field stations each summer — a resurgence that Kress calls “beyond my wildest dreams.”

It’s a gorgeous evening in mid-July, and Kress is in one of his favorite places on the planet: the Audubon camp on Hog Island, Maine, where he has spent many of the past forty-five summers and now serves as director. It’s after dinner, and the campers — adults taking one of this week’s courses, either “Art & Birding” or “Raptor Rapture” — are hanging around convivially, sitting in Adirondack chairs or clustered at picnic tables. Some are chatting, others sketching, and a few are singing along to a Hog Island ditty set to the tune of the Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine.” (“We all live in an osprey camp in Maine, an osprey camp in Maine . . .”)

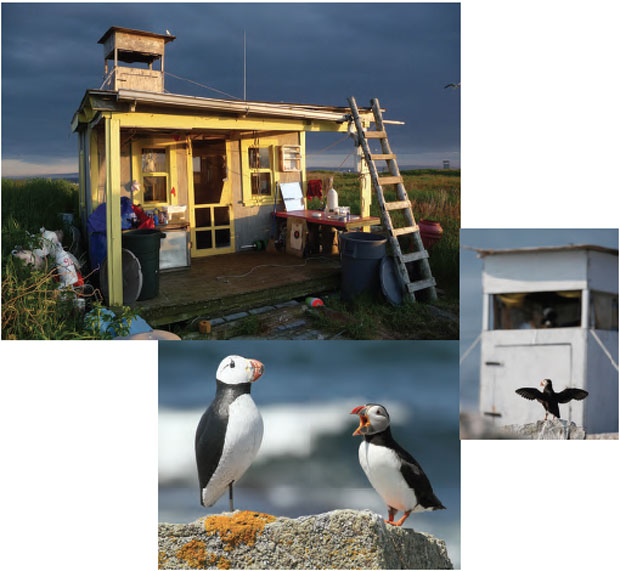

Maine events: (Clockwise from above) Observing the action from a blind; a puffin chats up a decoy placed to attract the social birds; and the sun sets on the modest hut known as the Egg Rock Hilton.

Nearby, Kress’s wife, Elissa Wolfson ’81, and their young daughter are enjoying some pre-bedtime nature exploration. Perched on a log bench, Kress looks out over the water as the sun sets and the mosquitos intensify their nightly assault. A pricey gold watch glitters on his wrist — an emblem of his status as a Rolex Laureate, an honor that his conservation efforts garnered in 1987. “Why is it important to protect species?” he muses. “Why not let nature take its course? I had that question from the beginning of the puffin project. Some would say that there should be a new order, where the only species left would be those that could live in the wake of humanity. I don’t accept that. We have the ability not just to destroy species but to conserve them — to establish populations where humans have wiped them out.”

That’s exactly what Kress did on Eastern Egg Rock. In 1973, back when he was a CALS grad student with a mop of curly black hair, Kress spearheaded an effort to restore puffins to the seven-acre spit of land, where the Atlantic puffin had long nested before being hunted into oblivion. It was tedious, dirty, exhausting work — and it required a massive leap of faith, since it would be a full eight years before Kress and his fellow “puffineers” saw their labors bear fruit. Kress describes those efforts in Project Puffin: The Improbable Quest to Bring a Beloved Seabird Back to Egg Rock, published in April by Yale University Press. Coauthored with Boston Globe journalist Derrick Jackson (but written in the first person from Kress’s perspective), the book chronicles what would become not only the world’s first successful seabird restoration project, but a model for some four dozen subsequent efforts by like-minded conservationists around the globe. “My initial goal was to see puffins at Eastern Egg Rock — but how many would be there? I had no idea,” Kress says. “How long it would take? I had no idea. When I started this, I thought it would probably be a few years. Now, the irony is I don’t see an end to it.”

Kress’s scheme to bring puffins back to Eastern Egg Rock, which is located about seven miles southeast of Hog Island, hinged on a fundamental fact of the birds’ reproduction: while they spend most of their lives at sea, they return to their own hatching grounds to breed. While that posed a challenge — there’s no use in relocating adult puffins, since they’ll just seek their natal rocks at breeding time — it also opened the door to Kress’s ingenious solution. After obtaining the requisite permissions, the puffineers spent years relocating hundreds of chicks (a.k.a. “pufflings”) to Eastern Egg Rock from a vast colony in Newfoundland, Canada. They built artificial burrows — to avoid predators, puffins nest underground — painstakingly cleaning and maintaining them, and hand-feeding the chicks with thousands of small fish, each supplemented with a vitamin pill in its piscine mouth.

The hope was that after the chicks fledged, spent several years maturing at sea, and returned to land to start their own families, they’d consider Eastern Egg Rock their home. To attract the puffins — a social bunch that senses safety in numbers — Kress had the novel idea to employ decoys, mirrors, and audio recordings. (The puffineers also had to rid the island of black-backed gulls, predators that would scare the puffins away — and whose numbers had skyrocketed thanks to the proliferation of garbage dumps and lobster bait.) It wasn’t until 1981 that the first nesting pairs of puffins were sighted on Eastern Egg Rock, a moment that Kress calls “euphoric.”

Make way for pufflings: Interns dive into burrows (top) to inspect the babies (middle). Above: Kress and a colleague banding a bird early in the project. Left: Kress and a puffin on Eastern Egg Rock.

The next morning, Kress pilots a motorboat out to Eastern Egg Rock, navigating through a persistent but picturesque fog. It’s about an hour-long trip from the Audubon camp, past such evocatively named landmarks as Wreck Island and Devil’s Elbow. “It just looks like any other Maine rock, doesn’t it?” Kress says as Eastern Egg comes into view. “You wouldn’t guess that something special happened here.” His passengers — which include Lab of Ornithology board member Louisa Copeland Duemling ’58 and two of her guests — cry out in glee when the first puffin appears, soon to be joined by several compatriots. “They know Steve is here,” Duemling offers. “They have to come out and say, ‘Thank you for saving me.'”

In addition to the approximately 150 breeding pairs of puffins, the island is home to three species of tern — birds that Project Puffin has also worked to restore, in part because they help defend against predators. Egg Rock also hosts Maine’s largest colony of laughing gulls, a species that co-exists with the puffins — and whose vast numbers, cacophony of calls, and tendency to dive-bomb visitors inevitably evokes a certain Alfred Hitchcock thriller.

Visiting Egg Rock requires transferring from the boat to an inflatable skiff, rowed by one of the half-dozen interns that spend the summer there. The accommodations are rustic: an outhouse, tent platforms, and a twelve-by-twelve-foot hut dubbed the Egg Rock Hilton. The latter serves as a combination office, kitchen, hang-out space, and library; it houses, among other things, the detailed journals that puffineers have been keeping since the project began. “The interns here today are surrounded by all these puffins,” Kress notes as he shows his guests around, “but for the interns forty years ago, it was like, ‘Whoa — will we ever see one?’ ”

Each morning, the interns take up residence in one of the blinds, where they painstakingly record details of the birds’ activities — noting such information as the type and number of fish they deliver to their chicks, who are nestled inside rock burrows that the researchers have marked with red-painted numbers. “Some of the burrows have long histories,” Kress explains, as a dozen or so puffins swoop through the air, bob on the waves, and congregate on the rocks below. “For example, Burrow 16 — that’s where the oldest puffin in North America bred. That bird hasn’t been seen in a couple of years, but we keep watching for her, because nobody really knows the behavior of puffins at the older end of their life cycle. That bird — Y33 was her name — bred until she was thirty-five. Whether she’s still alive or not, we don’t really know.”

While the puffins of Eastern Egg Rock have become such a fixture that they’re now a popular tourist attraction — observation boats circle the island daily in the summer — Kress stresses that their status remains precarious. If the interns didn’t live on the island during the breeding season, for one thing, black-backed gulls would eventually wipe them out or scare them off. Mammalian predators, like otter and mink, also pose a danger — and then there’s the increasing threat of climate change. Its effects are already being felt: some chicks have died from choking on warmer-water fish that are too wide for them to swallow. “This puts a face on climate change in a real-time way,” Kress says. “There’s the poor polar bear on the melting ice flow — and now the poor puffin choking on the oversized tropical fish.”

Like polar bears, puffins are photogenic ambassadors of the animal kingdom. And indeed, each year some 1,500 of them are “adopted” in donation programs, a third via Audubon and the rest through Barbara’s, which donates to the project on behalf of each customer who enrolls in the Adopt-a-Puffin program by sending in twenty UPC codes from its cereal boxes. Kress notes that on top of the birds’ appealing demeanor are their humanlike attributes: they practice long-term pair bonding, return to the same burrow year after year, and cooperate to raise their young. “People can easily anthropomorphize them and relate to them in ways that’s harder with other birds,” Kress says. “If I were working on some nocturnal storm petrel, it probably wouldn’t be as appealing.”

Puffin Peeping During the breeding season from April to August, you can watch Project Puffin in action from your laptop at explore.org. The Seal Island field station offers views from three webcams: a burrow, a “loafing ledge,” and a boulder berm that shows the birds commuting from the sea.

Welcome to Egg Rock: (Above) The seabird enclave under an ominous sky; (Right) measuring a puffin beak— which, like tree rings, can indicate age.

FLIGHT OF FANCY

For one student, and internship to remember

While many of his fellow undergrads spent their summers toiling behind a desk, Liam Berigan ’17 enjoyed sun, sea — and puffins. As an education intern with Project Puffin, Berigan lived in Bremen, Maine, a hamlet just across the water from Hog Island. “I’m essentially here to get people excited about puffins,” says the CALS biology major, taking a break from his duties in late July. “It’s fantastic. I get to meet a ton of new people every day.”

While many of his fellow undergrads spent their summers toiling behind a desk, Liam Berigan ’17 enjoyed sun, sea — and puffins. As an education intern with Project Puffin, Berigan lived in Bremen, Maine, a hamlet just across the water from Hog Island. “I’m essentially here to get people excited about puffins,” says the CALS biology major, taking a break from his duties in late July. “It’s fantastic. I get to meet a ton of new people every day.”

The Virginia native was among hundreds who applied for eighteen intern positions last summer. His job (which offered a stipend as well as room and board) included narrating boat tours around Eastern Egg Rock, where tourists jockey to observe the seabirds. “There are days when you see gigantic blocks of puffins in the water and you can get really close to them,” Berigan says. “That’s always special, because oftentimes they’re rather shy.”

To get a feel for the conservation biology side of the project, Berigan spent two weeks at a field station at Seal Island National Wildlife Refuge, home to a restored colony of more than 500 nesting pairs of puffins, among other species. “You get to be so close to the birds, 24/7,” he says. “And you get to watch the chicks grow up, which is incredibly cool.”

Berigan’s other main duty was staffing the project’s visitor center, which features exhibits like a scaled-up puffin burrow that kids can crawl into. The center also supports Project Puffin through the sale of all manner of swag. Among Berigan’s personal favorites? A fan shaped like a puffin — a.k.a. a “puff-fan” — and some novelty boxer shorts. “They have a puffin wearing sunglasses,” Berigan notes, “and they say ‘Stud Puffin.'” And yes: before the summer was out, Berigan picked up a pair.

Sea Change

In an excerpt from Project Puffin, Steve Kress ponders the birds’ future

I once thought that “sustainable” means getting puffins in Maine to a population where they could survive on their own as they did before European settlement. Four decades of work has convinced me that this is not likely to happen. That in turn raises an obvious question that I must answer for skeptics. Is there any lasting importance in a project where, if I stopped it, the gulls and eagles would return and wipe everything out?

I argue yes because these puffins are a living definition of modern stewardship. Even a remote jumble of boulders like Eastern Egg Rock in relatively sparsely populated Maine cannot escape human effects.

Egg Rock is an island connected to the mainland, not by a bridge but by a web of creatures from plankton to predator. The most obvious such connections are garbage landfills and the fishing waste of passing lobster boats. These support huge numbers of gulls, and each gull is always looking for the next meal.

Another connection to burgeoning coastal humanity is that the very successes of coastal wildlife conservation and changes in land use over the past century have nurtured other voracious threats to the puffin. New England, once a region clear-cut by farming, logging, and urbanization, has become reforested to its highest levels since the Civil War. These forests are now home to eagles, great horned owls, mink, and otter that are capable of finding their way to even the most remote island nesting seabird sanctuaries. The more success we have in building up the seabird numbers at Egg Rock and other restored seabird nesting islands, the more predators will come — because the seabirds are food, and if there is a meal to be had, something will eat it. I am convinced that if predators were permitted to snack at will on the small colony of puffins and terns at Egg Rock, all of our tedious efforts to revive the colony would be lost. Similarly, if we were to let down the guard for even a summer, the aggressive black-backed and herring gulls would gobble up most tern chicks.

The haunting questions I have long pondered are: How could this system have survived without human assistance for so long before our arrival? What happened that makes it necessary to manage the birds today?

I have come to believe that increased human presence and associated enterprise not only gives advantages to some species over others but usually leads to simple biological communities with fewer species dominated by generalists and scavengers. We see it on land with gulls, crows, vultures, raccoons, pigeons, and rats replacing habitat specialists such as wood thrush and meadowlarks. Likewise, the ocean floor around Egg Rock is also a simpler habitat than in centuries past. Commercial fishing emptied nearby waters of big fish such as cod and halibut. Even invertebrates like sea urchins and starfish are now largely replaced by crabs and lobsters, because scavengers readily fill in the ecological opportunities vacated by more specialized animals.

It is increasingly clear that the “sustainability” in Project Puffin lies not in finding an exit strategy but in its ability to restore seabirds to historical locales by expanding ranges and increasing the number of nesting colonies. In this way, we are reducing risk from a variety of extreme threats. Building populations to greater numbers during years of plenty also helps the population thrive during lean years or after some catastrophic event such as an extreme winter storm or havoc caused by a predator.

Future seabird conservationists will have not only to focus on defending existing colonies but to find ways to move birds to safer habitats in the coming years. This will become increasingly urgent because there are already about three times more people living within seventy miles of a coastline than the global average density. Here, seabirds and conservationists must contend not only with the old challenges of predators, poachers, toxic spills, development, and the occasional volcano but also the need to anticipate broad effects from climate change.

Just as canaries were once used to test the air quality in coal mines, so birds today are warning us of degraded and dangerous environmental conditions. Disappearing eagles, ospreys, and peregrine falcons once helped to make the effects of DDT visible to us. In the same way, crashing populations of warblers now tell us that there is too much logging in rainforests in Central and South America and too much cut-up, fragmented habitat in the United States.

Likewise, seabirds are sentinels of the ocean. They are messengers about climate change and the health of fish populations because the numbers, size, and kinds of prey delivered to their chicks inform us about changes in the abundance, diversity, and distribution of coastal fish. Overfishing and climate change are altering the world’s fish populations at a frightening speed unimagined when we started our project in 1973.

Excerpted and condensed from PROJECT PUFFIN: THE IMPROBABLE QUEST TO BRING A BELOVED SEABIRD BACK TO EGG ROCK, published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2015 by Stephen W. Kress and Derrick Z. Jackson. Reprinted by permission.