When the 1918 edition of The Elements of Style landed on E. B. White’s desk at the New Yorker in March 1957, his memory of the book was hazy. It had been sent by a classmate and friend, Howard Stevenson ’19, editor of the Cornell Alumni News. The previous summer, when the Stevensons visited the Whites on their farm in Maine, the men had reminisced about Professor William Strunk Jr., PhD 1896, and Stevenson had made a mental note to dig up a copy of the professor’s thumbnail credo and send it White’s way. He had finally succeeded in unearthing, from the university library, a copy that had been deposited there by Strunk himself, and the library staff was pleased to let Stevenson pass it along to White ’21, who, at that point, was one of Cornell’s most well-known alumni.

Stevenson’s gift, the book White held in his hand, was a wisp of a thing, more along the lines of a pamphlet, the approximate size of the instructions for your digital camera or a brochure presented to you by your dentist, a perky tract about flossing or gum disease. Five inches wide and seven inches tall, it was forty-three pages long and saddle-stitched—that is, held together by two wire staples crimped through the book’s spine. The cover was lightly textured card stock, gray-tan with a narrow navy stripe running top to bottom at the spine, front and back. The cover design was a clean graphic implementation of the Strunkian aesthetic, a simple key-lined box surrounding only the essentials. The booklet had been privately printed, according to the small type near the bottom of the copyright page, by the Press of W. P. Humphrey, Geneva, N.Y.

‘It was known on the campus in my day as “the little book,”‘ White wrote, ‘with the stress on the word “little.”‘

White was charmed by the gift and by the memories it evoked of his old professor, who had died eleven years before Stevenson’s gift arrived. Almost immediately, White began plans to write an admiring piece about Will Strunk and The Elements of Style for the New Yorker. White’s essay about Strunk appeared in the July 27, 1957, issue, under the heading “Letter from the East.” The Strunk reminiscence is sandwiched between two largely unrelated sections of the “Letter”; the first is about White’s battles with mosquitoes in his Turtle Bay apartment, the last a rueful warning about the mismanagement of radioactive waste. The mosquito piece moves, in its final paragraph, to the question of trimming the excess from one’s life. The Whites were then in the midst of packing up their affairs in New York and preparing to quit their apartment and move full-time to the farm in Maine. “Every so often I make an attempt to simplify my life,” White wrote, “burning my books behind me, selling the occasional chair, discarding the accumulated miscellany.” One of the books he had decided to neither burn nor leave behind was “a small one that arrived in the mail not long ago, a gift from a friend in Ithaca.” White then introduced the world to William Strunk and The Elements of Style.

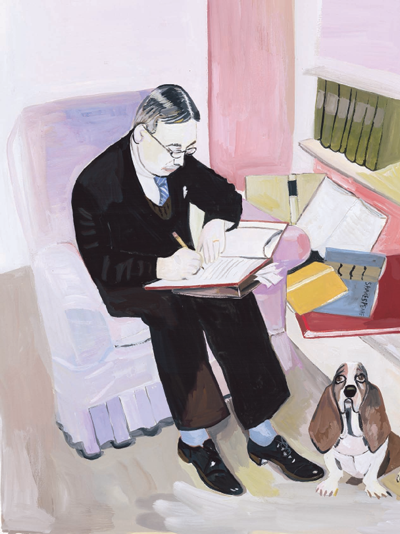

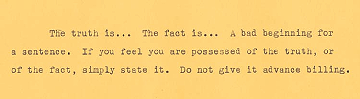

“It was known on the campus in my day as ‘the little book,'” he wrote, “with the stress on the word ‘little.'” Elements, White said, had been Strunk’s attempt to gather the principles of good writing “on the head of a pin,” and he drew a lively verbal portrait of Strunk, who emerged as archetypically professorial—blinking at his charges from behind round, steel-rimmed spectacles, holding his lapels and leaning over his desk to deliver his positive, if sometimes eccentric, style-related pronouncements in loud, confident tones. The essay made clear White’s admiration for Strunk’s qualities as a teacher and a man, and his respect for Strunk’s devotion to the principles of style he preached. “I treasure The Elements of Style for its sharp advice,” White wrote, “but I treasure it even more for the audacity and self-confidence of its author. Will knew where he stood.” By the end of the essay, readers were cheering along with White for the memory of Strunk, admiring and maybe a little envious of the professor’s certainty, of his fervor for intellectual and moral clarity in a world gone soft. In that issue of the New Yorker, the “Letter from the East” is long, its columns thinly threaded through a gauntlet of advertisers targeting the magazine’s affluent, culture-conscious readers, making for a wry contrast with White’s meditations on simplicity and Strunk’s admonitions about bunk: Abercrombie & Fitch, Ballantine’s Scotch, Cadillac (“Without a Word Being Spoken . . . a new Cadillac car states the case for its owner with remarkable clarity and eloquence”), United Airlines (touting the juicy steaks on their for-men-only “Executive” flights from New York to Chicago), and a full-page spread of a leggy knockout in Capri pants enjoying a Pabst Blue Ribbon beer with her man.

The same week the essay was published, White was contacted by Jack Case, an editor at the Macmillan Company, who told White that if The Elements of Style was everything White had made it out to be, Macmillan might be interested in republishing it. Case and his boss, the assistant director of the company’s college department, Harry Cloudman, felt the book’s unique, somewhat eccentric qualities were just what the market was crying out for, as Case made clear in a letter pitching to White the idea of their republishing the book, using White’s New Yorker essay as its introduction, before anyone at Macmillan had even laid eyes on The Elements of Style.

White heard from others, too, Strunks among them. Will’s son Oliver ’21, by that time well embarked on his own teaching career at Princeton, wrote to thank White for the touching tribute to his father. Oliver was particularly pleased by the glimpse that White’s essay had given him of Will Jr. at work, since the Strunk children had never been allowed in their father’s classroom. White also heard from fellow Cornellians who were grateful to see Strunk memorialized in this way. One, an antiquarian bookseller in Ithaca, wrote to White in November and said that his phone had started ringing eighteen hours after the New Yorker essay on Strunk had appeared and had been ringing “ever since”—White’s readers were seeking out any existing copies of The Elements of Style.

Before the deal could be completed, the matter of copyright had to be considered. The Elements of Style had been revised and republished several times since the original 1918 edition, and it had been a Harcourt, Brace publication since 1920. The last version, published in 1935, had been revised by another Cornell instructor, Edward A. Tenney, PhD ’32, and released as The Elements and Practice of Composition, with a section of exercises added to the back of the book. It took Case and Cloudman nearly a year, from the summer of 1957 to the spring of 1958, to sort out the copyright status of the various editions. The Strunks, Emilie and her son Oliver, the executor of his father’s estate, were happy to see the project move forward, and Oliver was helpful early on in Macmillan’s efforts to identify the various editions and investigate any existing copyright claims. In May 1958, Case wrote to White to let him know they had finally established that the rights were free and clear, that nothing stood in the way of copyrighting a new edition of The Elements of Style with White as coauthor. Macmillan was ready to offer a contract, with the royalties split fifty-fifty between White and the Strunk estate. Case went on:

We now believe that unless THE ELEMENTS OF STYLE were to be reissued simply as a kindly memorial to its author rather than as a useful book for the second half of the century, certain editorial changes would have to be made, and that you are the person to make them. I think you will at once feel a reluctance to lay violent hands upon something that was once well done. Actually what we should ask would not amount to this. . . . We don’t think that the various suggestions quite add up to a revision of Professor Strunk’s book, to actual rewriting, or to deletion and substitution that he would not himself want to make if he were here to do so, except with regard to two or three crotchety passages based on excessively personal aversions. We should like to have you saw off bits of outdated scroll work here and there, and then build onto the sound essential structure some advice of your own about the elements of good writing. Just where the joints would come and how they would be made could be worked out later; first we should like you to form your own picture of the dimensions of the remodeling to be done.

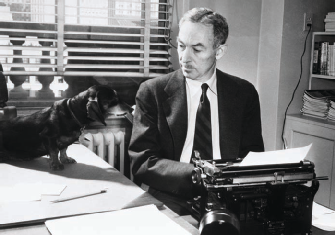

With a clear road before him, White threw himself into the job. Far beyond simply adding his reworked New Yorker essay to the book, he committed to a thorough edit of Strunk’s original text and the contribution of a new chapter on writing—the “bit more” he had mentioned “on the subject of rhetoric.” At the start of the project, Case sent White a photostat copy of Strunk’s edition, with the pages pasted onto individual sheets of typing paper, for White to mark up with his changes. White eventually found it an impractical way to proceed and ended up retyping most of the book from scratch, revising as he went. White posted the complete manuscript to Jack Case three days before Thanksgiving Day.

24 November 1958

Dear Mr. Case:

The book goes off by registered mail today, in three envelopes—one, two, three. I hope it reaches you before you sit down to your turkey. My chapter on style runs long, but I let myself go, being a white-haired old man, mumbling in my corner. . . . I’ll be very glad to have your estimate of my remarks on style. Do they fit this book, or are they out of place in a Strunk murder? You may shoot at them with anything from a gum eraser to a poisoned arrow; the only thing I can’t stand is to have my feelings spared, or an editor failing to say what is on his mind.

Sincerely,

E. B. White

P.S. I have no copy of my piece, or of anything else, so if you lose it, lose it good and we can all just relax.

Sixteen months after first learning of Strunk and The Elements of Style, Case and Cloudman were ecstatic to finally have White’s completed manuscript in hand. Case wrote back to White, giddily: “It has arrived. It looks fine. Harry Cloudman and I are going to smudge it up with cranberry sauce at my house tomorrow. . . . Congratulations on hitting your deadline right on the nose!”

After Jack Case and Harry Cloudman had read the manuscript closely, Case wrote an appreciative letter to White.

I have been plugging away at the manuscript almost continuously since it arrived, and so have not had a chance to tell you how much we like it. By Thanksgiving evening both Harry Cloudman and I had read all of it once and parts of it twice, and were quoting to each other sentence after sentence of the final chapter.

That is a fine thing, delightful and wise, as we knew it would be—from the fun about cats to the startling Wolfe quote, and your equally startling treatment of it, both of which would make a corpse sit bolt upright; from the gentle, firm counsel not to thrash about in the stream to the sharing of your hard-won glimpses of the mysterious heart of style. All this, and much more, is not only wonderfully good in itself; it fulfills our common purpose to make those matters of writing come alive for the reader who needs help, and to keep them as clear as may be . . . .

The typescript of the 1959 edition—a sizable stack of White’s preferred yellow typing paper interleaved with corrections, inserts, taped-in sections from Strunk’s original text, and instructions for typesetter and printer—is preserved in the White collection at Cornell. For an Elements of Style disciple, it is an inspiring sight, imparting something like the electric thrill of proximity to history I felt when leaning over the Magna Carta in the subdued lighting of the British Library. An artifact from the days of typewriters, colored-pencil corrections, and paste-up, a physical typescript is a reassuring thing to see and hold in this age when books routinely travel the complete route from author to printing press in the digital realm without materializing, corporeally speaking, until they emerge from the bindery. A typescript of the old style is a gloriously untidy stack of papers with the real-world presence of a created thing—a flapping, pasted, taped-up offspring born from toil, the living output of an artisan at work. In a manuscript that has been through an editorial round or two, a good portion of the process of authorial refinement is laid bare, and you can watch over the shoulders of author and editor as decisions are made, various lines of approach essayed and abandoned, thoughts and expression sharpened.

In the 1959 typescript, White’s clean-typed pages, double-spaced pica, have been layered over with penciled printer instructions and editorial comment—indentations indicated, caps and itals duly underlined, typefaces and spacing between paragraphs called out in point sizes. Some penciled lines have been crossed out, some smudged out, some scratched over with pen and new words typed above; words, phrases, sentences, and whole paragraphs have been written in by hand and circled, with lines guiding them to their proper places in the text. Strips of paper have been glued in here and there with corrections, pasted over sections they’re replacing. In places, whole pages from Strunk’s original Elements have been taped in; they, too, are covered with editorial graffiti, the cellophane tape browning and brittle, some of its glue turned to dust. Some inserted pages are entirely handwritten, penciled in White’s strong, sharp hand. White’s New Yorker essay about Strunk, most of which is used as the book’s introduction, has been clipped directly from the magazine’s pages and pasted in strips onto two pages of white typing paper.

Through the winter of 1958-59, The Elements of Style was put through its editorial paces at Macmillan and refined with a good deal of back-and-forth between New York and the farm in Maine. Jack Case gathered opinions from experts in the field, and White, as promised, sought the “inestimable advantage” of his wife’s editorial opinion. Katharine’s involvement in the enterprise was energetic and substantial, and she provided White with several sets of typed notes that addressed the expert critiques Case was collecting. During this period, Case was also lining up marketing efforts for the book, and to that end inquired whether White would be willing to make an appearance at an upcoming Macmillan sales conference and speak to the assembled sales force. White’s reply was a characteristically droll refusal, and also a playful indication of how much the final cleanup of Elements was occupying his thoughts.

Through the winter of 1958-59, The Elements of Style was put through its editorial paces at Macmillan and refined with a good deal of back-and-forth between New York and the farm in Maine. Jack Case gathered opinions from experts in the field, and White, as promised, sought the “inestimable advantage” of his wife’s editorial opinion. Katharine’s involvement in the enterprise was energetic and substantial, and she provided White with several sets of typed notes that addressed the expert critiques Case was collecting. During this period, Case was also lining up marketing efforts for the book, and to that end inquired whether White would be willing to make an appearance at an upcoming Macmillan sales conference and speak to the assembled sales force. White’s reply was a characteristically droll refusal, and also a playful indication of how much the final cleanup of Elements was occupying his thoughts.

In answer to your request that I say a few words to the trade and college salesmen I’ll have to acquaint you with the nonspeechmaking side of me—almost the only facet that amounts to anything. As for lunching with you at the Players’, that I’d like. All the stuff has arrived and I am at work on it. But mine is a strange existence, between barn and house. It is not always clear to me whether I am watering a calf or milking a strunk. But I do my best.

The Elements of Style (by William Strunk Jr., With Revisions, an Introduction, and a New Chapter on Writing by E. B. White) was published in late April 1959. Sales were good, and reviews in the popular press were almost unanimously favorable. The New York Times: “Buy it, study it, enjoy it. It’s as timeless as a book can be in our age of volubility.” The Boston Daily Globe: “The Admirable Mr. E. B. White . . . has lately performed another public service of the first magnitude.” The Cincinnati Enquirer: “Anyone who writes for public consumption would be doing himself and his readers a good service by reading over these pages at least once a month. There are only 71 of them.” In a short review on White’s home turf, the New Yorker noted that in its “brevity, clarity, and prickly good sense, it is, unlike most such manuals, a book as well as a tool. . . . His old teacher would have been proud of him.”

Elements was a May 1959 selection of the Book-of-the-Month Club. By August, between Case’s college-text printings and those of his colleagues supplying the general trade bookstores, there were 60,000 copies in print. By November the book was riding high on best-seller lists (third in the New York Times and Time magazine, second in the Chicago Tribune, first in the Washington Post). At the end of its first year of publication, The Elements of Style had sold an astonishing 200,000 copies.