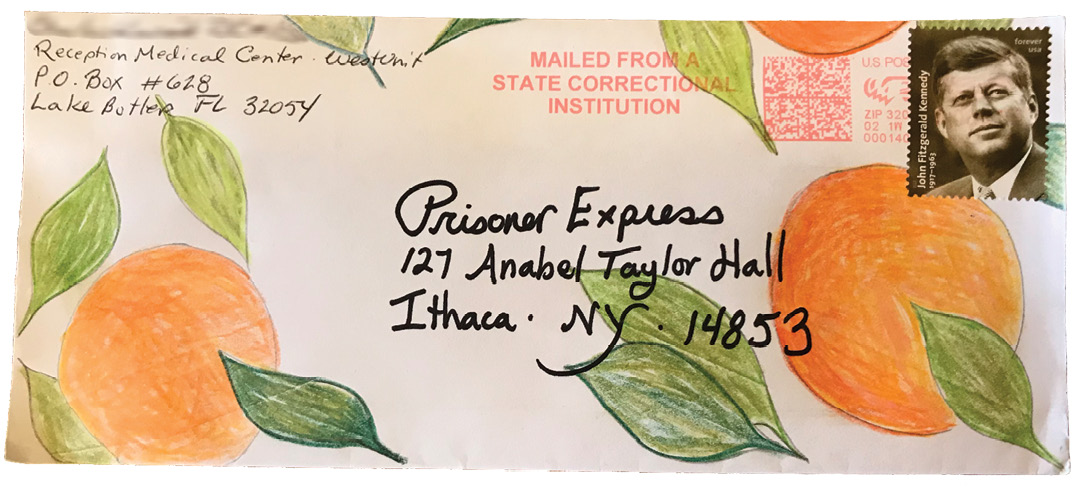

One of the many handwritten letters that Prisoner Express receives each week.Hobbes Elliot

At 5 p.m. on a Tuesday afternoon in April, about a dozen student volunteers filtered into Anabel Taylor Hall’s Durland Alternatives Library, turning the usually quiet study space into a bustle of whispered activity. Cardboard boxes were retrieved from behind the circulation desk, each overflowing with envelopes of various sizes—some with a handwritten address, some typed, others decorated with colorful doodles. CALS business major Min Lee ’19 headed to the back of the room, where a cart had been prepared with stacks of books ready to be wrapped, addressed, and mailed. She grabbed one pile and thumbed through it: there was a book on writing, another on the supernatural, a third on sculpture. On top was a letter from the books’ intended recipient, the return address bearing a name and a number—his inmate ID.

The letter is one of hundreds that arrive at the library each week for Prisoner Express, a Cornell-based outreach program for inmates across the United States. The program—which has served more than 25,000 people since its inception and has some 4,000 current clients—relies on student volunteers and library employees to respond to the letters, prepare packages, and curate newsletters that are mailed to prisoners. “Prisoner Express is dedicated to rehabilitation through outlets of creativity and expression,” explains Agnes Kwak ’19, who was involved with the program her sophomore through senior years, “whether that be through writing, reading, or learning.”

Kwak—a biology major in Human Ecology who volunteered with Prisoner Express through a service fraternity and liked it so much that she got a job at the library—oversaw the journal-writing program, which encourages prisoners to reflect and think critically about their lives. The journals themselves, which inmates mail to Durland, take up shelf after shelf of cabinet space, some participants having submitted entries over the span of many years. In 2018–19, Kwak spearheaded a project to digitize the journals, in the hope that they’ll someday be collected into a book; the Prisoner Express website currently features a small selection of journal entries from about a decade ago as well as art, essays, and poetry created by prisoners. “I wanted to find a way to reach a larger audience, to allow them to see what life is like for these prisoners,” Kwak says. “They really are inspiring in some sense, and there’s a lot that we can learn.”

Prisoner Express began in 2001, after Gary Fine, the library’s program director, received a letter from a prisoner requesting books. Fine put together a small package, and the man wrote back thanking him not only for the reading material, but for taking the time to write a friendly note. Fine began sending books to more prisoners across the U.S.—and thinking of other ways he could enrich their lives. Often, he says, the inmates were in solitary confinement, with little opportunity to interact with others, improve their skills, or express themselves creatively. “Education is shown to be one way to break the cycle of incarceration,” Fine notes. “If prisoners get out feeling connected and grateful for their chance to grow, they’re more likely going to behave.” That motivated him to begin Prisoner Express’s bi-annual newsletter, which publishes fiction, nonfiction, memoirs, and artwork received from prisoners over the previous few months. The success of the newsletter—which goes out to more than 2,000 inmates on the organization’s mailing list nationwide—has led to multiple offshoot pamphlets, each created by students, on topics ranging from cooking to oceanography to how to get a book published. Prisoner Express also creates short story collections and poetry anthologies from prisoners’ submissions, with copies mailed to each contributor.

Since its inception as a small one-man operation, Prisoner Express—a nonprofit that relies on donations of funds and books—has evolved to be one of Durland’s biggest outreach efforts, both in terms of labor and space. A large corner of the library, sectioned off by a partition, serves as the program’s mailroom. Boxes overflow with letters. Scattered around the shelves are artworks that prisoners have sent: papier-mâché fantasy characters, watercolor portraits, a sculpture of Touchdown the bear with the Cornell “C”; one painting, entitled View, consists of dark bars and shadows crisscrossing the canvas with one tiny, green rectangle of grass in the center. Many of the works have been featured in a showcase of prisoner art held annually at the Big Red Barn. Sometimes, the show has a theme; two years ago, for example, prisoners were asked to submit paintings made with coffee, a nod to the lack of art materials behind bars. Last year, one student organized a project entitled Moth and Light, asking prisoners to submit drawings and editing the images together into a two-minute video that followed the fictional journey of an insect that keeps returning to a prison, even after it is set free.

Student volunteers prepare books for shipment in Anabel Taylor Hall’s Durland Alternatives Library last spring.Hobbes Elliot

Prisoner Express’s most popular program remains the one that first inspired Fine—the book distribution service, which typically provides each recipient with three to five volumes at a time. Prisoners often write asking for particular titles, but since most of the books—which are stored and organized in the Anabel Taylor basement—are garnered through donations or heavily discounted sales, staffers and volunteers generally can’t honor specific requests, instead matching them as closely as possible. (While Prisoner Express requests a small donation from prisoners to go toward postage, the books themselves are provided for free.) Among the interactions that were most memorable for Breonna Freeman ’19, an animal sciences major in CALS who oversaw the book program last year, was one from an inmate who was interested in Sudoku. After mailing him a few sheets of puzzles, she says, “I received a response saying, ‘You made my year,’ because no one else had taken the time to do that.”

Prisoner Express attracts students from a wide variety of majors and backgrounds, some of whom enjoy the experience so much they stay involved throughout their Cornell careers. A common motivation many cite is the opportunity to set aside their own concerns and help someone else. “You have to put all of your mind toward writing a letter, making a package—it’s a very hands-on process,” says Freeman, adding, “It’s easy to get caught in the Cornell bubble. This program gives students an outside view of the world. They realize what a privilege it is to have access to the education and resources that we do.” But participants acknowledge that it can be hard to reconcile the friendly correspondence with the crimes of which the inmates have been convicted. “It’s still shocking,” admits Kwak, recalling that in one of her first interactions through the program, “a prisoner admitted that he was in jail for first-degree murder—and along with that letter, he sent me a couple of friendship bracelets he had made.”

Working with prisons can be logistically challenging, too. Regulations on what can be mailed vary state by state and facility by facility; a newsletter or package can be denied for any number of reasons, from prohibitions on potentially inflammatory subject matter to regulations designed to prevent the smuggling of contraband. (For example, some prisons have recently restricted the use of stamps, since drugs could be secreted beneath them.) Volunteers have come up with creative work-arounds: when an inmate in solitary confinement was prohibited from possessing hardback books because the covers could theoretically be used as weapons, a student simply cut the covers off. In another instance, a prison rejected a newsletter because it included a DIY chess board—readers could cut out the board and pieces—on the basis that sending toys and games was prohibited. Instead, volunteers sent the board in one packet and the pieces in another, and both were accepted.

Fine notes that while most of the prisoners who participate in the program remain fairly anonymous, with all communication conducted via mail, he did have the opportunity to meet one beneficiary. “Ten or fifteen years ago, a guy walked into the library and said, ‘You Gary?’ ” he recalls. “He shook my hand and said, ‘I just had to say thank you. You really helped me a lot.’ And he turned and walked out. Didn’t even say his name.”