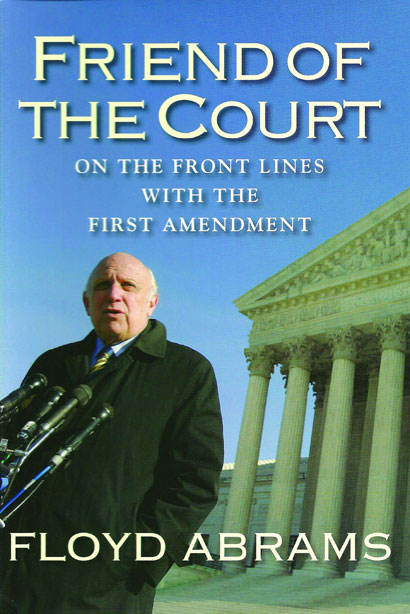

Floyd Abrams ’56 has argued more First Amendment cases before the United States Supreme Court than any other lawyer. Few of them, including New York Times v. The United States (the Pentagon Papers case), have been easy.

As his new book, Friend of the Court: On the Front Lines with the First Amendment (Yale University Press), demonstrates, Abrams is a near First Amendment absolutist. He celebrates the triumph of “good speech” over “bad speech,” but believes that only a society willing to allow bad speech to circulate can truly be free.

Friend of the Court is an immensely informative and provocative collection of writings in which Abrams weighs in on a wide array of free speech issues, including libel laws, pornography, “hate speech,” WikiLeaks, Internet “publications,” and the Supreme Court’s recent ruling in Citizens United v. FEC, which barred Congress from criminalizing independent expenditures by corporations and unions supporting or opposing candidates for federal office. He is equally tough on liberals and conservatives, Democrats and Republicans. The Reagan Administration, he indicates, severely limited the scope of the Freedom of Information Act and subjected government officials to lifetime pre-publication review. Bill Clinton signed the Communications Decency Act, which made it a crime to post on the Internet material that was “indecent” or “patently offensive” to children under eighteen, despite the claims of Newt Gingrich, among others, that it clearly violated free speech and “the right of adults to communicate with each other.” Abrams counts the ways in which, on free speech, the administration of George W. Bush was “something else.”

Abrams is especially tough on liberal opponents of Citizens United, including President Obama. On more than two dozen occasions, he reminds us, the Supreme Court has extended First Amendment protection to corporations. More than sixty years ago, justices Wiley Rutledge, Hugo Black, William O. Douglas, and Frank Murphy—probably the most liberal quartet ever to sit on the Court—concluded that the “undue influence” obtained by large contributions was offset by the “loss for democratic processes resulting from restrictions on free and full public discussion.” Abrams shares liberals’ concern about the impact of economic inequality on politics; he maintains, however, that regulating how much speech is allowed to groups in the sixty days before an election “is contrary to the core of the First Amendment.”

Acutely aware that “speech has a price,” that Nazis marching in Skokie and racists burning a cross on the lawn of a black family can wound and terrify, Abrams takes pains to show that fears about the impact of speech “seem invariably overblown.” Ten years after the publication of the Pentagon Papers, he tells us, not one person, including members of the Nixon Administration, could cite a single passage that had done damage to national security. He insists as well that in the 2010 midterms, the first post-Citizens United election, “the much predicted one-sided corporate takeover of the political system did not occur.”

It is surprising to discover, then, that, “notwithstanding its obvious threats to civil liberties,” Abrams strongly supported the USA-PATRIOT Act, passed in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. Persuaded that the terrorist threat to our individual security “is unparalleled in American history,” he appears not to have submitted that legislation to his own test: “Any proposed limitation on recognized civil liberties should be the least intrusive or constitutionally threatening way of accomplishing the end sought and there must be a very close fit between the problem and the solution.” In 2006, it’s worth noting, Abrams expressed deep concern that the Justice Department refused to reveal how often it had used the Act to expand surveillance and executive authority.

One wonders what he thinks now, especially in light of his reminder that government will use its power “to skew public discussion in its favor”—and his recommendation that those who complain the wrong side keeps winding up with the First Amendment in its corner should rethink their political positions “to avoid being on the wrong side of the First Amendment.”