Percy’s portrait in the 1966 Cornellian.

Even after five decades, emeritus professor of psychology James Maas, PhD ’66, vividly recalls the early morning phone call from his housemate, a staffer at WVBR. “He said, ‘Jim, I’m reading what’s coming over the AP wire right now, and your friend Valerie has been murdered,’ ” he says. “It was like a horrific dream.” In shock, Maas went outside and—scarcely knowing what to do with himself—started mowing the lawn. “I think I mowed for three hours,” says Maas, then in the early years of teaching the now-legendary Psych 101 course that would continue until his retirement in 2012. “And it was a very small lawn.”

For Maas, who counted Valerie Percy ’66 among his closest Cornellian friends, it was a devastating personal tragedy. For the nation, it was a shocking crime—one that remains unsolved to this day.

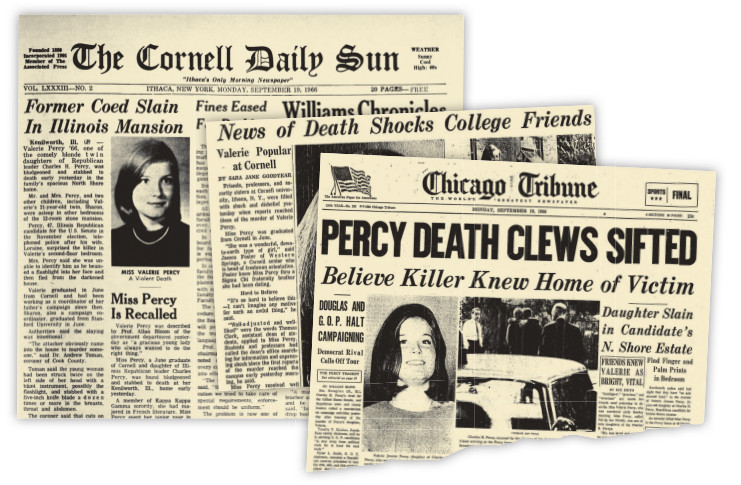

The daughter of a successful Chicago-area manufacturing executive, Percy was just twenty-one and newly graduated from Cornell when she was killed in the pre-dawn hours of September 18, 1966, in the family’s elegant home on the Lake Michigan shore. The crime made national headlines: the Ivy League-educated child of a U.S. senatorial candidate had been bludgeoned and stabbed to death in her own bed by an unknown intruder, in an affluent suburban village where violent crime was all but unheard of.

Modern forensic science was in its infancy; DNA testing was decades off, and small-town police departments were often ill-equipped to cope with major crimes. Although some potentially promising evidence was gathered at the scene—including a glove and a moccasin—it was never matched to a perpetrator. A bayonet recovered from the lake wasn’t definitively identified as the murder weapon. The only eyewitness—Percy’s stepmother, who entered her bedroom when she heard sounds of distress—didn’t get a clear look at the killer as he rushed past. Although the crime may have been connected to a cluster of burglaries in the area, the fact that nothing was taken from the Percy home cast doubt on that theory.

Valerie Percy had graduated from Cornell only the previous spring, having majored in French literature. Linda Bernstein Miller ’66, one of her Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority sisters, recalls that Percy was thrilled to spend her junior year in Paris and adored French music. “She listened to Edith Piaf day in and day out,” Miller remembers, calling Percy “a happy, loving, beautiful person. She was gorgeous to look at and wonderful fun to be around. She laughed all the time.” Fellow Kappa sister Mary Wellington Daly ’66 remembers her with equal fondness. “Val was cheerful, optimistic, unpretentious, humble, gracious—beautiful inside and out,” she says. “When she entered a room it was as if she were floating in on a breeze. Rarely was she not wearing a most radiant smile.”

On campus, Percy’s mentors included famed philosopher Allan Bloom—future author of The Closing of the American Mind—then a professor of government. In the Daily Sun the day after her death, he eulogized her as “a gracious young lady who always wanted to do the right thing.” In news stories, Percy was lauded as friendly, open, and down-to-earth despite her family’s wealth and status. “Considering the fact her family is very prominent and she had every right to be a snob,” the late Sandra Stone Bugge ’67, Percy’s Kappa “little sister,” told the New York Times, “she was one of the most sincere and unpretentious people I knew.”

At the time of Percy’s death, she was planning to pursue a master’s in international studies at Johns Hopkins; she’d spent the summer doing campaign work for her father, Charles Percy, a Republican senatorial hopeful considered to have presidential potential. “Val was very, very close to her father,” Daly recalls. “Although her personality would not lead you to believe that she would throw herself into a political campaign, she willingly, eagerly, and tirelessly campaigned for her father during his Senate run.” When news of Valerie’s death broke, his opponent—Democratic incumbent Paul Douglas—immediately sent condolences and pledged to temporarily halt campaigning. The race resumed after the funeral; Charles Percy went on to win, serving three terms until he was unseated in 1984 by Senator Paul Simon.

In 2013, Chicago journalist Glenn Wall self-published a book about the case, Sympathy Vote: A Reinvestigation of the Valerie Percy Murder. (The title refers in part to the notion that Charles Percy’s grief may have prompted some Illinoisans to cast ballots in his favor.) In it, Wall identifies a man whom he calls an overwhelmingly likely suspect: William Thoresen III, the emotionally disturbed scion of a wealthy family that lived near the Percys. Thoresen, who’d been in regular trouble with the police since his youth, was suspected of numerous crimes including the murder of his own brother; four years after the Percy killing, Thoresen was shot to death by his wife, who successfully claimed self-defense.

Valerie’s murder, Wall notes, “is one of the better known cold cases,” still discussed and debated in online forums. Just last spring, it resurfaced in the courts. New York attorney John Kelly—who has represented the families of well-known homicide victims including Nicole Brown Simpson and Natalie Holloway—filed suit to compel several law enforcement agencies to release records about the Percy investigation. Kelly says that his motives are personal rather than professional: he grew up in the Chicago area, was thirteen at the time of the murder, and has an abiding curiosity about the case. A hearing in the suit was held in mid-August, with a ruling likely several months off.

Even though fifty years have passed since Percy graduated from Cornell, her memory remains alive on the Hill in a small but meaningful way: a scholarship in her name that her friends, sorority sisters, and others endowed decades ago is still being awarded annually. With the aim of enabling current students to share one of her most treasured experiences, the Valerie J. Percy Junior Year Abroad Scholarship provides funds for female undergrads to study in France. “Every year, I get beautiful letters from the recipients,” Miller says. “It’s a very loving, wonderful memorial to Valerie.”