The American Art Museum’s stately Lincoln Gallery.

On the third floor of one of the oldest federal buildings in Washington, D.C., the avant-garde decor stands in dramatic contrast to the historic setting. Here–in space where Abraham Lincoln held his second inaugural ball and Walt Whitman read poetry to convalescing Civil War soldiers–is a massive, wildly colorful multimedia installation, dubbed Electronic Superhighway, that depicts the fifty U.S. states in a pastiche of audio and video. Nearby, a twenty-eight-foot-tall column of white LED lights undulates with swirls of alternating text, while a man-sized fabric sculpture, entitled Soundsuit, evokes a faceless alien clad in a festively embroidered dress.

Joanna Marsh, a senior curator at the Smithsonian.

This distinguished collection belongs to the nation: it’s part of the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum. And since 2007, it has been the focus of Joanna Marsh’s professional life. Marsh ’99 spent eight years as curator of the museum’s contemporary art, recently segueing into a newly created position–senior curator of contemporary interpretation–aimed at spurring visitor engagement with its modern holdings, roughly defined as dating from the Sixties to the present. “We’ve been doing a tremendous job with our acquisitions and exhibition program, but that’s not enough; we also need to think about how the visitor wants to interact with the artwork,” says Marsh, a former double major in art history and English literature who holds a master’s degree from the Sotheby’s Institute in London. “Contemporary art is probably the most challenging area in the museum for the average visitor, and we felt we weren’t connecting with them as deeply as we could. The idea is to build new interpretive strategies, both in the gallery and online, that will provide a bridge between the content we produce and the public’s understanding of it.”

Contemporary art is probably the most challenging area in the museum for the average visitor.

While Marsh’s efforts are still in the planning stages, she says that avenues for deepened engagement include the use of new media, reimagined signage, innovative programs led by curators and docents, increased emphasis on adult education, and collaborations with colleges and universities. “I want people to feel unintimidated by the process of looking at contemporary art, but that’s not the case right now for most visitors,” says Marsh, who interned at the museum as an undergrad and spent six years curating contemporary art at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut. “We want them to come away wanting to learn more, whether it’s visiting another museum or going online to read more about a particular artist–to spark curiosity, as opposed to having people feel that contemporary art isn’t for them and dismissing it.”

Housed in the original home of the U.S. Patent Office, the American Art Museum is adjacent to the National Portrait Gallery, to which it’s connected by a dramatic, recently constructed glass atrium. Together, the two attract some 1.3 million visitors a year. And while tourist stalwarts like the Museum of Natural History–home of the Hope Diamond and the ever-popular dinosaurs–may pack in more than five times as many warm bodies, Marsh notes that the art museums’ comparatively sedate traffic has its advantages. “Our million visitors a year is nothing to sneeze at,” she says, “but it affords ample time and space for intimate and meditative experiences in our galleries, where you’re not elbow to elbow with other visitors.”

During Marsh’s tenure as contemporary art curator, she spearheaded the acquisition of numerous works. She also curated special exhibitions, including “The Singing and the Silence: Birds in Contemporary Art,” for which she sought inspiration at Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology. The show won her a Smithsonian research prize–which she received from none other than former University president David Skorton, now head of the institution. “One of the things that attracts me to contemporary art is that the artists are encouraging you to dig deeper. You don’t just stop at the surface; there is often a more substantive message being conveyed,” Marsh observes. “Many contemporary artists comment on important issues–social, political, cultural, environmental–that are relevant to all of us living in the United States today.”

|

Guided Tour Marsh offers a primer on some of the pieces she acquired |

|

Picnic “There’s something nostalgic about this piece, but also contemporary. There’s very subtle messaging. You have these pairs–apples, ice cream cones, cupcakes, slices of pie–that are slightly different from each other. You ask yourself: is this a commentary on gender differences, sexual orientation, politics? He leaves that up to the visitor. What is the significance that this picnic is happening on top of cinderblocks–that this is not a pastoral scene? Is that a commentary on the loss of green spaces? There are so many different ways to read this work.” |

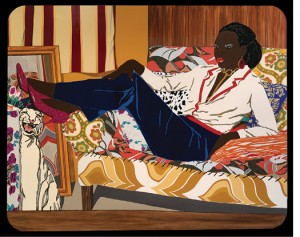

Portrait of Mnonja “Thomas is known for striking images of strong female protagonists, and also for incorporating rhinestones onto the painted surface, so you have this glittering effect. I think one reason that she uses them is to comment on the ways we adorn ourselves, and the idea of forming identity–the way women in particular use makeup and clothing to create an image or persona. The pose of the figure is a kind of traditional odalisque, like Manet’s, so she’s referencing precedents from the nineteenth century and even earlier.” |

Manifest Destiny “It’s a post-apocalyptic view of New York City, an image of the Brooklyn Waterfront several hundred years in the future. This is a comment on what the world might look like after humans have had a dramatic impact on the environment–the rising sea levels, warming waters. The artist is presenting us a view of what looks like sunrise, so an inherent optimism is built into it; humans are gone, but life persists. Because of its scale–it’s twenty-four feet wide–it really does immerse the viewer. It’s one of Rockman’s seminal works, a tour de force.” |

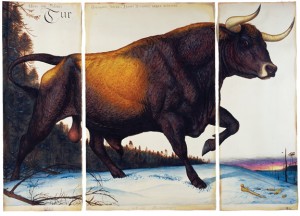

Tur “This was the first acquisition I made for the museum. Ford is best known for large-scale watercolors of endangered and/or extinct species, allegories of how man has impacted the Earth or wildlife; this is a prehistoric bull that went extinct in the seventeenth century. Another signature feature of his work is that he channels nineteenth-century naturalist imagery, particularly John James Audubon and the Hudson River School of painters. You come to this and think it couldn’t be contemporary, but in fact it is. So perhaps a visitor who is more inclined toward nineteenth-century imagery would gravitate to a piece like this.” |

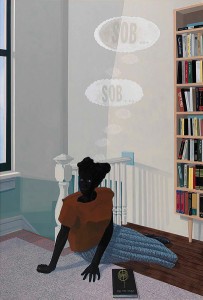

SOB, SOB SOB, SOBKerry James Marshall “We wonder: what is she lamenting? What is she sobbing about? Is it the history of Africans and African Americans? She’s got a book in front of her that says “ÜAfrica since 1413,’ which is when it began to be colonized. Why is she sitting on the floor at the top of the stairs? Is she looking out a window or into another room? There’s a kind of awkwardness to her pose and her clothing, something out of time; by showing just one leg of the bookcase, it creates a sense of instability. It’s a simple painting, but once you start to unpack the imagery, it becomes increasingly complex.” |