Richard Jay Potash ’71—better known by his stage name, Ricky Jay—has had an eclectic career, to say the least. He’s an actor who has appeared on TV (“Deadwood”) and in movies (Boogie Nights). He’s a historian of magic and carnival acts, penning a book on the subject entitled Learned Pigs & Fireproof Women. He’s a designer of special effects whose firm, Deceptive Practices, devised the wheelchair in Forrest Gump that concealed actor Gary Sinese’s legs, making him appear to be a double amputee. He’s one of the world’s leading sleight-of-hand artists; in the mid-Nineties, his Off-Broadway show of magic and card tricks, Ricky Jay and His 52 Assistants, played to packed houses. It featured, among other marvels, Jay impaling a watermelon with a playing card from ten paces.

Richard Jay Potash ’71—better known by his stage name, Ricky Jay—has had an eclectic career, to say the least. He’s an actor who has appeared on TV (“Deadwood”) and in movies (Boogie Nights). He’s a historian of magic and carnival acts, penning a book on the subject entitled Learned Pigs & Fireproof Women. He’s a designer of special effects whose firm, Deceptive Practices, devised the wheelchair in Forrest Gump that concealed actor Gary Sinese’s legs, making him appear to be a double amputee. He’s one of the world’s leading sleight-of-hand artists; in the mid-Nineties, his Off-Broadway show of magic and card tricks, Ricky Jay and His 52 Assistants, played to packed houses. It featured, among other marvels, Jay impaling a watermelon with a playing card from ten paces.

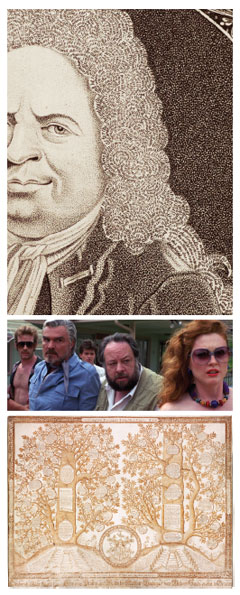

Detail of a self-portrait by Matthias Buchinger, in which his wig comprises lines of miniscule lettering spelling out Psalms and the Lord’s Prayer. (Photo: New York Times)

Jay’s latest endeavor is devoted to another highly colorful character: Matthias Buchinger, a German who lived from 1674 to 1739. As the New York Times put it in a recent story on Jay, Buchinger was “a magician and musician, a dancer, champion bowler, and trick-shot artist, and, most famously, a calligrapher specializing in micrography—handwriting so small it’s barely legible to the naked eye.” Jay has been collecting Buchinger’s work for decades, and his holdings are the subject of a show—“Wordplay: Matthias Buchinger’s Drawings from the Collection of Ricky Jay”—running at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art through April 11.

To accompany the Met exhibit, the art publisher Siglio has come out with a sumptuously produced (and eccentrically titled) hardbound volume: Matthias Buchinger: “The Greatest German Living” by Ricky Jay, Whose Peregrinations in Search of the “Little Man of Nuremberg” are Herein Revealed. The book chronicles Jay’s adventures in researching Buchinger—who was born without hands or feet, yet somehow produced lettering so small it could scarcely be read without a magnifying glass. “He was by turns lauded and denigrated, celebrated and denied the right to perform,” Jay writes, “and declared dead long before his actual demise at sixty-five.” The book also reproduces numerous works by the calligrapher, whose personal life was apparently as eventful as his professional: though he stood just twenty-nine inches tall, Buchinger married four times and fathered fourteen children. As Jay notes: “Buchinger is unique, but it is both possible and essential to contextualize him.”