E.B. White

E. B. White ’21 wore many hats. Author of children’s books (including the beloved Charlotte’s Web); co-writer of the classic grammar guide The Elements of Style; longtime New Yorker essayist; all-around raconteur. Another lesser-known title: dog-lover. White owned dogs throughout his life—though he may well have argued that they owned him. He wrote on many canine-related topics over the years, from comically fraudulent “reports” by his elderly dachshund, Fred, to coverage of assorted run-ins between four-legged Manhattanites and the law.

Last spring, Maine’s Tilbury House published a hardcover collection of White’s canine writings, edited by his granddaughter, Martha. E. B. White on Dogs features New Yorker stories, poems, letters, essays, sketches—even a moving obituary to his Scottie, Daisy, run down by a yellow cab that jumped the curb. Many of the pieces evince both White’s signature wry wit and an abiding understanding of the dog-lover’s lot. “My advice, if you have a dachshund puppy, is to subscribe to the New York Times,” he wrote to a friend in 1950, “and instead of reading it just distribute it liberally all over the house.”

Among the book’s entries is “Architects and Dachshunds,” published in the New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town” section on Sep tember 3, 1949:

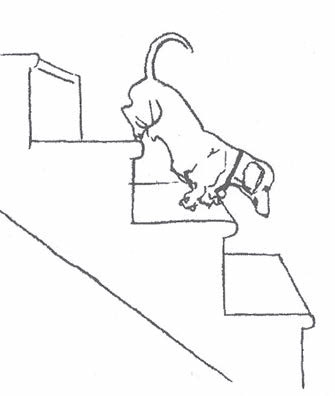

Serious consideration should be given by architects to the problems of people who own dachshunds. The modern boys—the Wrights, the Gropiuses, the Neutras—are full of startling ideas about functional design, but it is one thing to design a house around a person and it is something else again to design a house around a dachshund. Chief of the problems is the matter of stairs. Here, proportion is everything. An English setter takes a flight of stairs in his stride—literally in his stride, one paw after another. He merely crouches slightly and glides up or down. A dachshund, because of his low center of gravity (which in some individuals is simply a center of frivolity), is incapable of going up and down stairs one paw after another. He, or she, must tackle stairs in a series of bold, sometimes hysterical leaps, the two forepaws and the two hindpaws operating in pairs. The ascent of a dachshund is a sort of conniption. It requires considerable driving power, most of it supplied by the hind legs. The descent, far more difficult and in some instances disastrous, is a series of suicidal leaps, with the dog in imminent danger of nosing over. lf you have never studied the descent of a dachshund, perhaps a brief description will help. The animal first gets himself into the correct launching position, forepaws down one step, hindpaws poised at brink of takeoff. If he is an elderly dog, he remains in the launching position for several minutes, reviewing the situation and making side remarks. Having determined to go, he throws himself outward with just enough force to drop him onto the next step down, still in the launching position. Obviously he must neither overshoot nor undershoot. And he must re-launch himself the very instant he makes contact; that is, he must continue to bounce, legs tensed and in pairs, one step at a time, till he reaches the bottom. A dachshund with long toenails descending an uncarpeted staircase makes a sound unlike any other sound in nature.

We can say with assurance that a stairway having ten-inch treads and seven-and-a-half-inch risers is a practical stairway for an adult dachshund in reasonably good health. A stairway with narrow treads—seven or eight inches, a size common in old New England houses—can cause a dachshund to crack up nervously. Circular stairs, popular with modern architects, are unfair to dachshunds; such stairs often have no risers at all, which is unnerving, and the descent requires not only a bounce but a bounce with a twist. Our own residence, built before either architects or dachshunds were highly thought of, is unsuitable for dachshunds, and we are thinking of installing an electric chair-lift for our animal. While we are at it, the chair might as well be big enough to hold both of us.

From E. B. WHITE ON DOGS. Copyright © 2013 by Martha White. Reprinted by permission of Tilbury House, Publishers, Gardiner, Maine. All rights reserved.