Jimmy Pitaro ’91 Phil Ellsworth/ESPN Images

Jimmy Pitaro ’91 works in a shrine to the New York Yankees—bringing a bit of the Bronx to suburban Connecticut. Vintage posters of Yankee Stadium and signed photos of legends Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle adorn the walls of his office, as does an image of catcher Thurman Munson, who died in a plane crash on Pitaro’s tenth birthday. Pitaro has a personalized autographed poster from his childhood favorite third baseman, Graig Nettles, and several signed photos of this millennium’s superstar, Derek Jeter. In fact, he named one of his rescue dogs Jeter—which he thought best not to mention to the human Jeter when the two had lunch in 2018.

The first rule of sports journalism is “No cheering in the press box.” As president of ESPN, the world’s largest sports and entertainment network, Pitaro doesn’t just bend that rule—he clobbers it like Babe Ruth. “What, all of a sudden, now I’m at ESPN and I’m not going to be a Yankee fan anymore?” Pitaro says with an unapologetic smile. “My second-favorite team is whoever is playing the Red Sox. I have to be true to myself.” Furthermore, he says, his self-described “lunatic” devotion to the Bronx Bombers is an asset. As he explains, to understand how to reach media consumers, he has to think like a fan—the people who constantly check the ESPN app, faithfully watch or listen to its shows, and obsess over game stats. And to negotiate multimillion-dollar broadcast contracts with leagues, he has to understand trends and players in each sport. “To be successful in this job,” says Pitaro, “you have to be a sports fan.”

This March marks Pitaro’s second anniversary with ESPN, where he took the helm following eight years as chairman of interactive media and consumer products at its parent company, Disney. He arrived at a time when ESPN was in a leadership vacuum, reeling from the resignation of its president, John Skipper, who left to seek substance abuse treatment. Ratings were down as consumers cut cords, and layoffs had deflated morale. And the network had recently been caught up in a political skirmish: after the violent “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville in August 2017, ESPN anchor Jemele Hill called President Trump a “white supremacist” in a tweet, and the White House called for her to be fired. A month later, when she tweeted in support of NFL players in Dallas kneeling to honor the Black Lives Matter movement—which Trump had forcefully criticized—he called her out and mocked ESPN for its ratings decline.

With the network in danger of alienating its more conservative viewers, Pitaro sought to quell the controversy as soon as he started; politics, the data showed, was bad for business. He clarified ESPN’s existing policy: employees could not voice purely political opinions on air or social media. That drew more criticism from other media and some employees, and Hill ultimately left the network. “Somewhat lost in this whole narrative is that ESPN is ‘sticking to sports’—that’s not what we’re saying,” Pitaro explains. “If there’s a connection to sports, we’re going to cover it; we are the place of record. But we don’t believe that people tune in to ESPN for politics. My point of view is that it’s really hard to be really good in one field, and there’s so much competition right now. My job is to make sure we are amazing at delivering sports news.”

On the red carpet with his wife, actress Jean Louisa Kelly, at the 2019 ESPY awardsEric Lars Bakke/ESPN images

It’s a weekday in November, and Pitaro is sitting in his regular corner spot in a bustling coffee shop in suburban Connecticut, dressed in jeans and a sweater over a button-down shirt and sipping a kale smoothie. As he notes, his wife is away working, and his parents have temporarily moved in to help with the Pitaros’ two teenage children, a son and a daughter. His wife, Jean Louisa Kelly, is the more famous one in the family. An actor since childhood—she made her film debut in the 1989 John Candy comedy Uncle Buck—she has two movies coming out this year: Call of the Wild with Harrison Ford and the long-awaited sequel to the Tom Cruise blockbuster Top Gun.

Pitaro’s habit is to awaken before anyone else in the house—at 5 a.m., with planks, a Peloton workout, and a ten-minute listen to the “Calm” app to set his equilibrium for another demanding day. Atop his agenda: developing a younger audience through the direct-to-consumer market and integrating digital platforms like podcasts, Snapchat, and YouTube channels. Like other sports outlets, ESPN has been trying to figure out how to cover e-sports—and whether those are actually sports. (His son says they are.) Pitaro also constantly deals with the inherent tension between business and journalism, which means sometimes covering unflattering stories about teams and leagues with whom ESPN partners to broadcast games, like the New England Patriots’ internal dysfunction or the ongoing concerns about brain injuries among pro football players. Pitaro is well aware that ESPN’s contract with the league for Monday Night Football is up in 2021. “We can’t shy away from stories,” he says. “That’s a slippery slope.”

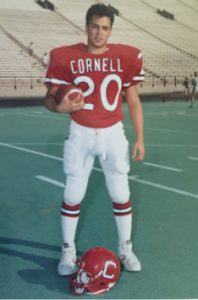

Pitaro on the Big Red gridironProvided

Pitaro came of age athletically at the same time as ESPN, which began broadcasting in 1979. If he wasn’t watching sports, he was playing them. He grew up in New York’s Westchester County in a Catholic household that rooted for the Giants and Notre Dame, but his father’s obsession with the Yankees set the tone in the house. Whenever they were playing, the family turned the television toward the table to watch during dinner. “Baseball was religion,” Pitaro says. (His sister, Lara Pitaro Wisch ’95, is now general counsel of Major League Baseball.) At Edgemont High School, Pitaro played baseball and basketball, ran track, and was a star running back. It would be the peak of his athletic life, and Cornell football recruited him hard. “I vividly remember meeting him,” says Pete Noyes, the Cornell Hall of Fame football coach who recruited Pitaro and retired in 2013 after thirty-six years on the Hill. “He had a super personality, just full of enthusiasm. And he was smart.”

Pitaro chose the College of Human Ecology, aiming to replicate the small-school feel of his high school. He played on the freshman football team, since it was an Ivy League rule at the time that freshmen weren’t allowed on varsity. But that year, Pitaro tore the medial meniscus in his left knee and had surgery. When he awoke, he was surrounded by four concerned doctors; they’d detected a heart murmur. He took sophomore year off from football, and, on the advice of doctors, avoided lifting weights. Twenty-five pounds thinner, he made the varsity traveling squad at wide receiver his junior year. But Pitaro broke his right thumb and played half the season with a cast. His football career was over.

He decided on law school after doing the Cornell in Washington program his junior spring, when a professor told him he’d make a good lawyer. After graduating with a degree in consumer economics and housing (as the major was then known), he went to St. John’s law school in Queens. He spent five years as a New York litigator—but, he says, “I didn’t like arguing with people every day. I wasn’t looking forward to going to work.” So when his wife was offered a role on a TV show shooting in Vancouver—one that promised to have a long run—he quit his job and they moved to Canada. It lasted just nine episodes, and they again packed up the minivan and drove south to Los Angeles. Her next show (the sitcom “Yes, Dear”) was a hit, and Pitaro eventually joined the music start-up Launch.com. Yahoo soon acquired Launch, and Pitaro went on to become the parent company’s head of media, after having turned Yahoo Sports into a news-breaking competitor to ESPN.

Launch’s founder—Silicon Valley executive Dave Goldberg, who was married to Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg and died suddenly in 2015—remains a powerful influence on Pitaro. Not only did he pave the way to Pitaro’s current post by introducing him to Disney chairman Bob Iger, he schooled him in some core tenets of corporate leadership: be accessible to employees, be responsive, and listen. Pitaro lives those lessons; he is a regular in line at the ESPN cafeteria, and holds frequent town hall meetings with the network’s 6,500 worldwide employees. (He also makes a point to e-mail fellow Cornellians at ESPN whenever Big Red athletes make national headlines.) “Every interaction I’ve had with him—whether it’s one-on-one, in a group setting, or speaking at the Cornell Sports Leadership Summit—he’s not trying to impress you. He’s not the boss,” says Jeremy Schaap ’91, an award-winning ESPN reporter who co-hosts its TV news magazine “E:60” and hosts the investigative show “Outside the Lines.” “He’s a smart guy who’s in this with all of us.”

At Yahoo Sports, Pitaro had built a brand around breaking news; he made sure that two of its top beat reporters were recruited by ESPN. To attract younger audiences, the digital streaming service ESPN+ (which launched in 2018) partnered with the UFC mixed martial arts league in 2019, and ESPN+ has since reached more than 3.5 million subscribers. The network also signed a deal with the mobile-only video service Quibi for a daily ten-minute highlight show starting this year.

Behind the scenes, Pitaro has worked to diversify the network’s talent and leadership. His executive team of ten has seven women on it; he promoted four of them. Before she met Pitaro, Sarah Spain ’02, an ESPN radio host and reporter, was concerned about what kind of leader he would be; his predecessor, Skipper, had been supportive of her career in a male-dominated industry. After Pitaro arranged a sit-down, she was encouraged to learn that he once quit a job for the sake of his wife’s career. They immediately clicked, discussing their Big Red experiences—Spain was co-captain of the track team—their love of rescue dogs, and their favorite Collegetown bars now gone. “We have a very easy rapport; it’s relaxed and comfortable,” she says. “I feel like at any point I can call him up and say ‘I’m pitching this story or this show,’ or ‘I want to talk about the direction we’re going.’ That’s really great for someone who’s got a lot on his plate.”

Pitaro recently joined Cornell’s Athletic Alumni Advisory Committee, a volunteer group of leaders from a variety of professions that offer counsel and insight to current student-athletes, coaches, and administrators. Other members include a fellow Alpha Tau Omega fraternity brother, Mike Levine ’93, co-head of sports at Creative Artists Agency. Levine calls Pitaro a “natural leader,” adding that he helped stabilize ESPN at a crucial time. “I think the focus he’s put back on sports fans and what’s happening on the field is working,” Levine says. “It feels like a very fan-friendly mentality. He recognized that in this time of political polarity, sports can be an escape and a connector of people who are on any side of any issue.”