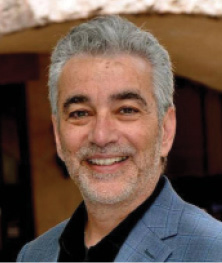

Bill Schutt

It was an invitation that many people—OK, make that most—would have politely declined. But zoologist Bill Schutt, PhD ’95, didn’t hesitate: he booked a flight to Dallas and took a friendly mother of ten up on her offer to let him eat the placenta she’d frozen after one of her pregnancies. The woman’s husband, a chef, served it up with beef stock, tomatoes, garlic, and onions.

The notable meal was consumed in the name of research for Schutt’s latest book, Cannibalism: A Perfectly Natural History. Published in February by Algonquin—on of all things, Valentine’s Day—it chronicles critters who eat their own species, from spadefoot toad tadpoles who grow teeth and chow down on their pondmates to snowy egret chicks who cope with food scarcity by killing and consuming their siblings.

In the book, Schutt—a tenured professor at Long Island University and a longtime research associate at the American Museum of Natural History—also explores cannibalism in people. Hence his curiosity about what human flesh tastes like, and the dinner invitation from a Texas mom and entrepreneur who promotes the health benefits for a new mother of consuming her placenta after childbirth. (Schutt’s culinary verdict: it had “a strong but not overpowering flavor,” he writes, with the consistency of veal but the taste of organ meat. He cleaned his plate.)

In the book, Schutt—a tenured professor at Long Island University and a longtime research associate at the American Museum of Natural History—also explores cannibalism in people. Hence his curiosity about what human flesh tastes like, and the dinner invitation from a Texas mom and entrepreneur who promotes the health benefits for a new mother of consuming her placenta after childbirth. (Schutt’s culinary verdict: it had “a strong but not overpowering flavor,” he writes, with the consistency of veal but the taste of organ meat. He cleaned his plate.)

Like Schutt’s previous nonfiction work—Dark Banquet, which describes the lives of blood-feeding creatures like vampire bats—Cannibalism is geared toward a scientifically literate lay audience. He compares himself to Mary Roach, bestselling author of popular-science books like Stiff (about methods of disposing of human remains) and Gulp (about the alimentary system). “The niche I’ve been able to carve out is where I take something that is misunderstood or thought to be gross and make it into something that is not only entertaining but enlightening,” he says. “Readers learn a lot of science without me banging them over the head with jargon.” He chose his latest subject, in part, because he saw a gap in the canon. “There were academic papers on cannibalism in nature and sensational books about cannibalism in humans,” he says, “but nothing in the middle.”

Schutt is chatting in his office in the museum’s mammalogy department, located on an upper floor in an area accessible only to staff. The halls are lined with vitrines containing a zoo’s worth of mounted skeletons, from a thylacine—an extinct, wolflike marsupial native to Tasmania—to a pygmy armadillo with a distinctive spade-shaped tail. Hanging from the ceiling are the bones of a dugong, Asia’s version of a manatee; row upon row of metal cabinets contain the museum’s world-class collection of study skins. “As far as animals, I’ve always been into really weird stuff,” says Schutt, whose elementary school yearbook listed his dream job as working at this very institution. “I had a monkey when I was a kid. I had lizards and collected under every rock. I’ve always been into the macabre and the strange—I grew up heavily influenced by people like Alfred Hitchcock—and I have a dark streak. That’s why none of my friends are surprised when they hear what I’m writing about.”

On the Hill, Schutt did his dissertation on the anatomy of the hind limbs of vampire bats—he’s still on the board of directors of the North American Society for Bat Research—and studied under Vet college zoology professor John Hermanson. “Bill has always been a good teacher and raconteur, and his books are an example of that,” says Hermanson. “When he taught intro biology here, students always said they loved the way he could tell a story or bring in a prop so the material would stick with you. He’s always had a way with words. He can turn a phrase and just crack me up.”

The female Australian redback spider, who devours her mates.

Indeed, in Cannibalism, Schutt often approaches the subject matter with a light touch. Take, for example, his description of the peculiar mating ritual of the Australian redback spider, which doesn’t end well for the male suitor. “Rather than allowing him to crawl off,” he writes, “the female wraps her shredded partner in silk, eventually snorking up his now enzyme-liquefied innards like a spider-flavored Slurpee.” Or, in a discussion about whether the Greek myth of Eros—Cupid to the Romans—was inspired by male snails who shoot fertile “love darts” at their mates: “Personally, I’ve always been a bit creeped out by the idea of a nude, weapon-wielding infant with wings,” Schutt writes, “but considering that the Greeks could have equipped him with turret eyes and a slime trail, I’m willing to cut the current incarnation some slack.”

Schutt stresses, though, that he’s more circumspect when dealing with human cannibalism, such as the genocidal horrors of Christopher Columbus’s calculated fictions about Caribbean natives. (Casting them as cannibals, Schutt writes, facilitated enslaving them for profit.) Schutt also describes societies—particularly in China, both during ancient times and as recently as the Cultural Revolution—in which cannibalism has been driven by political motives or the privations of war or famine, with families sometimes swapping children so they wouldn’t consume their own. He explores the phenomenon of “medicinal cannibalism”—a category that includes modern placenta-eating—and notes that in the early twentieth century, powders containing pulverized human bone were still being sold in some European pharmacies.

Among the research trips that Schutt took include a tour of the site of America’s most infamous cannibalism case: the Donner Party, the ill-fated 1846 expedition over the High Sierras whose starving, snowbound members resorted to consuming their departed companions. Schutt accompanied researchers aiming to pinpoint the true locations of the Donner camps—which may have been previously misidentified—using dogs trained to detect evidence of long-decomposed remains. For other sections of the book, he got to tour the lab of one of the world’s foremost dinosaur experts and wade through ponds in the Arizona mountains with museum colleagues studying cannibalistic tadpoles. Says Schutt: “I’m blown away by the people I get to hang out with for my research.”

In addition to his popular science books, Schutt pens genre fiction: last summer, William Morrow published Hell’s Gate, which he describes as a “World War II techno thriller with big vampire bats and nasty Nazi weaponry.” (The hero, touted in the book’s Amazon blurb as “a quick-witted, brilliant scientific jack-of-all-trades,” is essentially zoology’s answer to Indiana Jones.) The sequel, The Himalayan Codex, is set to come out in June. Schutt also has an idea for his next nonfiction work—but he’s keeping it under wraps, lest he get scooped. “I don’t think it has the gross-out aspect that the cannibalism book has,” he admits, “but it’ll keep me off the streets for a couple of years, and send me to some cool places.”